by James Generic

February 19, 2013

As a radical for more than half my life now, and a lifelong rabid sports fan, I don’t think being a politically engaged leftist person means you cease to be a human being. Yes, we don’t have to hide that we actually enjoy things in life that connect us with our larger society, a society we’d like to change. You are allowed to be a human being as a radical, whether you like sports, pop music, movies, or cartoons, and chances are, they aren’t all that separated from social and political change and may even have something to say about the society we live in.

Beyond all that, playing physical games on a regular basis can actually be pretty empowering. I am apart of a softball team founded on principles of trying to balance fun with competition. We try to keep a gender balance and have all sorts of people on the team, including some of my neighbors, as well as keep in mind values like anti-oppression, democratic organizing, and letting people develop at their own pace, whether they’re really good or have no playing experience at all.

For readers based in Philly, the Oregon Avenue Octopi softball team plays on Sundays at 10 AM at Marconi Park near Broad and Oregon. Look us up on Facebook for more information.

Why should anyone with a radical analysis of society care about sports? This question seems to sharply divide a good deal of society and radical thinkers, whom by and large reject any sort of deep analysis sports beyond thinking of mass viewership as a distraction, or opium of the masses, if you will. And then, on the flip side, those whom make it their business to follow sports tend to not care about sports as connected to social change. To me, this is an opportunity lost in the United States.

What are sports? Sports are a lot of things. At heart, they are simply organized physical games. But, like all things in capitalism, they have been expanded as another arena for profit and entertainment, to be battled over, and for power to be tugged back and forth between people involved, whether it be players, coaches, owners, fans, or others connected to the industry. Just like any avenue of power, it is not simply a top-down push with little resistance from below.

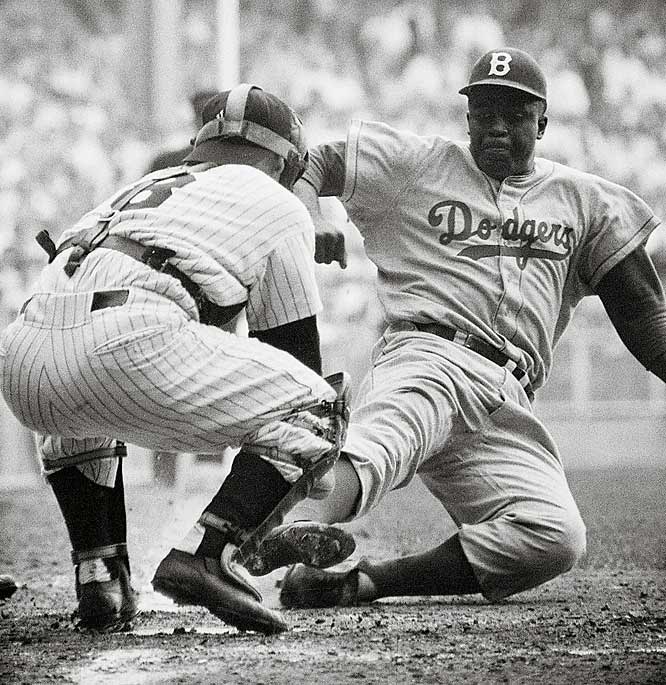

Jackie Robinson, first African American to play in the modern MLB

They are microcosms of society, and are decent barometers of how society stands on such things as race, class, gender, sexuality, and more. Indeed, sports can be a precursor of social progress, such as racial integration of Major League Baseball in 1947–or a sign of social distress, as present day MLB contains less than 10% African American players (a sign of crumbling infrastructure of inner-cities and lower college attendance rates as colleges shift scholarships to football and basketball, and MLB drafts more players out of college.) It can be a symbol of social liberation, such as the rise of the West Indies National Cricket team toppling the English teams, their former colonial rulers.

They can be grounds for both sides social wars, like when Don Imus made his “nappy-headed hoes” comment about the Rutgers women’s basketball team. They can ask deeper questions about social institutions, like why exactly do we segregate sports by gender? By and large, given equal access to training and resources, women can compete on the same field as men.

What connection does it have to education, agitation, and organizing? As a lifelong Philadelphia sports fan, I have been able to connect all my life with people from all sorts of backgrounds and political persuasions based simply on that common knowledge and experience of being a sports fan, something that transcends other sorts of entertainment fandom. That deep identification with the city of Philadelphia that comes with being a fan of the Eagles, Phillies, Sixers, Flyers, or whatever else automatically has given me “legitimacy” in conversations about the larger state of the world that I don’t think I would have had without it. Philadelphia has long had a history of betrayal by a conservative, inactive social elite (especially when compared with an active social elite of New York), and it follows with our sports teams. So complaining about how we’ve been screwed yet again by an inactive ownership gains immediate traction. And that is an invaluable organizing tool.

(A last side note, one of my favorite chants during the 2000s antiwar movement here in Philly was, “Less bombs! More touchdowns! Go Eagles!”)

James Generic is a long time Wooden Shoe Books collective member and a member of the Philadelphia branch of Solidarity.

Comments

2 responses to “Sports and Social Change”

Thanks for the article, James. The point about the urban pride displayed by sports fans having political implications got me thinking about the celebration I saw in Baltimore when the Ravens won the Super Bowl. Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, Baltimore has been a dominated by out-of-town capital, with many branches of nationwide corporations but few to no major companies headquartered here. Naturally, then, the city was hit pretty hard by the neoliberal restructuring of capitalism. In 1984, the then-Baltimore Colts relocated to Indianapolis. In the same period as the city was hit by waves of layoffs and closures at most of the major employers: Bethlehem Steel, Western Electric, General Motors… I wonder if Baltimoreans’ pride in once again having a kickass football team expresses a sense of resistance against capital flight.

(The ironic thing is that Baltimore got the Ravens the same way Indianapolis got the Colts—the current Baltimore Ravens used to be the Cleveland Browns. The move was facilitated through extensive subsidies from the government of Maryland for construction of a new stadium, opening the door for sports teams across the US to threaten to relocate unless they got massive subsidies—a process which, of course, furthers the wealth transfer that is neoliberal austerity. But this just illustrates your point that sports can be a useful avenue to begin political conversations with people.)

Of course, as you point out, it’s OK for socialists to like “normal” things. It can help us maintain our mental health and a feeling of connection with others. That’s why I’ve decided to watch a lot more football next season. (That, and I like drinking beer.)

Very cool article. I’ve always thought of sports–especially pro-level sports, but also the more casual variety–as a sort of proxy for many of the phenomena in our pluralistic, capitalistic society. What I find most compelling about sports from this angle is how it provides a legitimate arena for expressing some of the less savory aspects of human nature, and human society writ large. Die-hard nationalism is bad, but rooting for the U.S. soccer team to punch above its weight in the World Cup is totally cool (or for Boston to assert its superiority to L.A., even though I know there are plenty of wonderful people from Los Angeles). Our egoistic and aggressive urges to dominate others are the root of most of Capitalism’s problems, but hoping your team’s power forward absolutely demolishes his man on the low block is a much more benign expression of those urges. So I think you’re basically right that even radicals can enjoy sports for exactly what they are, and can use them as a way to vent our primal, competitive urges so that we may act more cooperatively in the social and political arenas.

p.s. Go Octopi!