by Dan La Botz

June 22, 2012

As Mexicans prepare to vote on Sunday, July 1 in the national elections, two presidential candidates have pulled ahead and each claims that he will win. Enrique Peña Nieto, candidate of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) that ruled Mexico for over seventy years, is ahead in all of the polls, buoyed up by the PRI’s political machine and the corporate media. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, candidate of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) who pulled into second place and has been gaining on the leader, has the backing of the organization that he spent the last six years building, made up hundreds of committees and tens of thousands of supporters. Peña Nieto might be called the center right candidate who will continue the neoliberal polices of the last quarter century and López Obrador the center left candidate who advocates what could be called social liberalism, capitalism with a human face.

The latest opinion polls show Peña Nieto likely to win 42 percent of the electorate and López Obrador only 30 percent. But López Obrador says the polls are wrong and his understanding of the Mexican people tells him otherwise. “We are going to win again,” he says, alluding to his claim to have won the Mexican election in 2006 only to have it stolen by the sitting president Felipe Calderón. Calderón’s colleague, Josefina Vázquez Mota, the candidate of the National Action Party (PAN) who hoped to become Mexico’s first woman president, has been falling behind, now at only 24 percent in the polls, dragged down by all the problems of Calderón’s presidency: the violence of the drug war that has taken 50,000 lives, the economic crisis, the lack of opportunity for the country’s youth.

The Impact of the New Student Movement

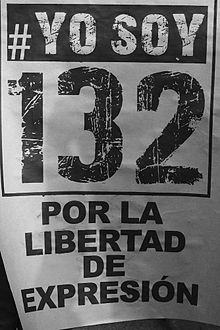

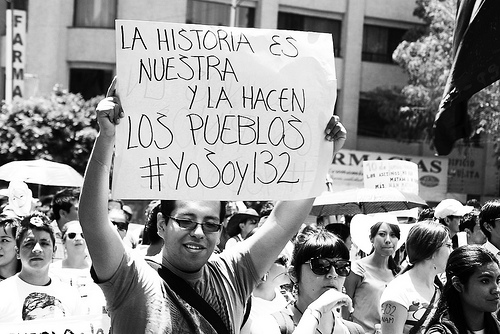

During the last several weeks the sudden upsurge of the new student movement in Mexico known as “I am 132” has begun to throw itself into the balance, and things now begin to tilt a little toward López Obrador, though it is not yet clear that they tilt far enough and fast enough to bring him victory. The new movement began when a group of socially-conscious students at the elite, private, Jesuit Ibero-American University in Mexico City protested against Peña Nieto for his record of violent repression of social movements in the State of Mexico where he was governor.

When Peña Nieto dismissed his youthful critics as a handful of 131 student protestors, others began to put their names and faces on the social media announcing, “I am 132.” Since then the movement has spread to Mexico public university system and now there are almost daily demonstrations throughout the country against the PRI candidate and the corporate media that back him. Marches in Mexico City have drawn tens of thousands and in other cities thousands, and they are marching everywhere and daily taking up new issues. The student protests have been fueled by the British Guardian newspaper’s reports that Televisa had been paid by Peña Nieto and other politicians to carry favorable coverage of their campaigns.

How Independent are the Students?

The appearance of what is now a national student movement attacking the alliance between the PRI’s Peña Nieto and Televisa clearly helps López Obrador, though both he and the students deny that there is any relationship between his campaign and the movement. The Mexican students say simply that they do not want to return to the past of the authoritarian, corrupt and repressive government of the PRI. The students sometimes call their movement “The Mexican Spring,” alluding to the Arab Spring of a year ago, and they invoke the Spanish indignados and the Quebec student strikes and protests which are taking place at the same time. The students argue that it is time for change in Mexico, though their movement has not yet articulated the kind of change they seek.

The PRI has accused López Obrador of using his organization and funds to manipulate the student movement, a charge denied by both López Obrador and the students who claim that they are completely independent.

On June 11, a new “Generation MX” (MX for Mexico) video appeared on the internet, supposedly made by half-a-dozen students, which criticized “I am 132” for serving party interests and having no direction. The video proved to have been made, however, under the direction of Rodrigo Campo, an advisor to the president of COPARMEX, the Mexican Employers Association, though Campo claimed that no political party had had any hand in the creation of the video or the alleged other new student movement that it claimed to speak for. The “Generation MX” video appeared to have been a failed attempt by one of Mexico’s most conservative organizations to derail the new student movement.

Photo: jpazkual

What Will Be the Impact?

Despite it’s unlikely beginnings at the elite Ibero, “I am 132” has become a genuine national youth movement, spreading from the Ibero to the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) with its 300,000 students, and then to other public universities across the country. The new student movement’s presence on the public university campuses and its protests and mass marches have allowed it to begin to have an impact on the country’s “ninis”—those who, because they don’t have the economic resources, neither study nor work (ni/ni = neither nor). The new student movement has also joined with other social movements, such as those that fight for the rights of Central American immigrants who suffer from police violence and corruption.

Whether or not this new movement is moving fast enough and becoming large and broad enough to help López Obardor’s campaign remains to be seen. If it survives the election, and his likely defeat, it could go on to have an impact on the society at large and possibly on the labor movement. Despite the massacre of hundreds at Tlatelolco, the Plaza of the Three Cultures, in October of 1968, many of the students of that generation went on to become activists in the labor unions and in other social movements; they joined left political parties and contributed to the struggles that finally ended the rule of the PRI in 2000. This generation of student activists, even if their activism doesn’t swing the election toward the populist López Obrador, may have a long term impact on Mexican society.

This article first appeared in New Politics. Dan La Botz is a Cincinnati-based teacher, writer and activist. He is a member of Solidarity’s National Committee.

Comments

One response to “On the Eve of the Elections: The Impact of the New Student Movement in Mexico”

A little correction to this story. The links between Televisa and Pena Nieto as exposed by the Guardian, were not just this electoral campaign. It exposed a link going back years, where the network, the second largest in Mexico and which, along with Azteca, control 80% of the free TV programming, was paid a minimum of $10,000,000 USD to raise his profile while governor of the state of Mexico, and in addition, used public funds to do.

The Yo soy 132 movement arose as the students of Ibero raised these questions to PN at a campaign stop, which proved a terrific embarassment to his campaign which responded by accusing the student questioners as outside agitators and provacateurs. The students responded by showing their Ibero student ID cards on the Internet, and the rest is very much as Dan LaBotz has written.

Sol

Elena

San Jose, CR