by Adam Hefty

November 9, 2011

Last Wednesday, Nov. 2, Oakland saw perhaps the most massive and militant day of action of the Occupy movement so far. Subsequently, big debates have opened up in Oakland and within the Occupy movement, online, at General Assemblies, and amongst friends and family over the success of the strike and where the movement should go from here.

Let’s start from some points of probable agreement. Conservative estimates in the mainstream media suggest a turnout of 5000-7500; activists involved estimate anywhere from 15,000 to upwards of 50,000 in the streets.

The action was not a general strike in the traditional sense. However, much of downtown Oakland was closed for the day, either in solidarity with the strike or in response to flying squadrons of picketers. The Port of Oakland was shut down for almost an entire day, resulting in tens of thousands of dollars in lost revenue. Several marches to and from the encampment targeted banks and particularly egregious employers. That evening, a group set out from the encampment to open a second occupation: the former Travelers’ Aid Society building, a property that had been foreclosed and sat vacant for some time. Soon after the beginning of this action, hundreds of riot police arrived in the area, dissipating this second action with a show of force: arrests, teargas, flashbang grenades, rubber bullets, etc.

Many people felt that a victorious day had ended with something of a setback, but had many different theories for why this might have been the case. Was the occupation of the Travelers’ Aid Society building an overreach? Were there problems with its execution, messaging, or tactics?

Mainstream press coverage over the next few days exacerbated this feeling for some; predictably, most accounts focused on property damage and street fighting. Did property destruction provide a pretext for police repression and an easy target for negative press? Or are the cops bound to repress and the mainstream media to misrepresent no matter what we do? They are institutions beyond our control, so blaming activists for what they do seems a bit perverse. Is it the case that a significant swath of the 99% in Oakland responded negatively to property damage in their city, as has seemed to be the case to many anecdotally, and how do we take account of that? To what extent should the movement make collective decisions about how to conduct itself, and to what extent do we need to honor the fact that various autonomous groups of activists in a large, messy process will self-organize and employ a diverse range of tactics?

What follows is a review of these debates.

The Property Destruction Debate

A big part of the debate centers around the Black Bloc, property destruction, “violence,” “peace police,” the relationship between action in the streets and police repression, the relationship between action in the streets and mainstream media representations, community response to and support of various actions, etc. At times, reading this debate, I’ve found myself wondering if I stepped into a time machine and stepped out in December 1999; in some ways, it’s the post-Seattle moment all over again, only with Whole Foods instead of Starbucks.

It’s worth pointing out that some of the critiques out there have been unclear re: what happened and the timeline of it. There are different sets of activities which seem to be particularly under debate: 1) targeted graffiti, window-breaking, and painting of big banks and Whole Foods, predominantly during or along the anti-capitalist march at 2 PM; 2) the occupation of the Travelers’ Aid Society building after 10 PM and its execution and conduct, especially the burning of barricades; 3) graffiti, window-breaking, and tagging that occurred near Oscar Grant Plaza after police had teargassed crowds near the Travelers’ Aid Society building, while a tense standoff was still underway, after midnight, some of which had an unclear relationship with the occupation (at least to me).

1) Critiques of Property Destruction

Davey D, journalist, hip hop historian, and radio programmer, raises some objections to property destruction that I’ve been hearing around Oakland: it is alienating to many in the community, it could contribute to Oakland’s negative reputation, and (relatedly) it makes it easy for mainstream media to portray the entire event in a negative light.

We heard and later saw video of a group of masked men dressed in black, spray painting the word “Strike” across the front of Whole Foods grocery store. Later on these same masked men broke the windows to Wells Fargo and Chase and tagged the walls. This enraged many on were on the scene, not because they felt sorry for the banks who would and did quickly repair the damage, but because they felt that what took place was a deliberate attempt to undermine what the General Strike was about. They also felt acts of vandalism were also gonna further soil the city’s reputation and give light to the stereotype of us being a crime ridden city….

Many waking up to the news of overnight violence were stunned, angry, and dismayed. Damn near every corporate news outlet was on the scene, including the NY based Today Show, who had pretty much ignored Occupy Oakland in the past, but this morning they had a reporter on the scene doing live coverage. Blaring across everyone’s screens wasn’t 20k people closing down the 5th largest port in the country, it was masked men wearing all Black setting fires in the middle of the street and destroying local businesses.

Davey D concludes that the vandalism may have been the work of provocateurs (a conclusion not widely shared, at least regarding the targeted vandalism during the anticapitalist march, since people have defended it politically). His entire writeup is worth a read; Davey D is an important Bay Area organic intellectual who covered the Oscar Grant protests extensively and who bridges local political divides.

A whole series of blog posts offered critiques of the black block or of property destruction as an immanent critique from within anti-authoritarian, anarchist, or global justice politics.

Americans against the Political System argues against hardening divisions in the movement and against liberal pacifism while also arguing against Black Bloc tactics as part of the Occupy movement. “[D]on’t show up at an explicitly nonviolent event and give the pigs an excuse. If this turns into a violent revolution we MUST make sure that that change is a deliberate and strategic one. For now, nonviolence is #OWS’s best weapon and one the cops and the media are trying to take away.”

A post on anarchistnews.org offers a contextual rejection of Black Bloc tactics for the current moment: “Is it always black block time? For me It’s not about whether black block, or the specific brand of minor protest violence it represents is “good or bad” it’s about whether or not it’s useful right now.”

A post on Indybay compares the Black Bloc’s historic role in Europe with the Black Bloc at Occupy Oakland and finds the latter wanting. “The mood and tone of the anti-capitalist march and the buildup to shut down the Port was joyous, inclusive, even festive. The mood and tone of the Black Bloc was aggressive, exclusive, and alienating. The reaction of the Peace Police was as predictable as the reaction of the proper police. Even if OO were the proper context to incite a rupture with the capitalist and statist foundation of modern American society, it certainly wouldn’t come at the behest of a self-selected vanguard of a hundred skinny masked white kids who disappear when a phalanx of riot cops shows up.”

One of the most nuanced, sustained pieces in this genre criticizes the particulars of property destruction in Oakland.

On an average day Downtown Oakland is full of the empty storefronts and collapsing infrastructure that characterize post-industrial America. The people who live downtown all fall within a spectrum of middle class, working class, or poor – some desperate and homeless. Many if not most residents of downtown are people of color and or immigrants. The people who work downtown are also largely brown and middle class or poor. They work in non-profits, social justice organizations, small community businesses, or in the case of the corporate outlets, local franchises that are in terms of financial risk and benefit for the local manager effectively also small local businesses. The majority who work at the few corporate offices downtown are not highly paid and likely feel pretty lucky to have jobs right now. When we break windows downtown, we unequivocally hasten the physical and economic deterioration of this space that is peopled by those we claim to want to defend. I cannot come up with one sane argument for trashing the homes and workplaces of Oaklanders, those who are clearly not the deciders of capitalist policies, not even on a very local level.

If this tactic of breaking windows, tagging and other property destruction is to be employed, Downtown Oakland is a very poor choice as a target.

Decolonize Everything offers another intro to this debate, calling “attention to the fine line which we must tread if we are to mend these self-destructive splits, continue to grow our movement and escalate our political mobilization.”

2) Debates over process and tactics at the Travelers’ Aid Society building occupation

The greatest furore of this debate focuses on property destruction (sometimes collapsing the deliberate, targeted property damage that happened on the anti-capitalist march with the tagging that occurred during a tense, late-night standoff with police), even though it seems that the occupation of the Travelers’ Aid Society building was the immediate event that triggered police repression. A wide range of people were excited about the potential politics of the second occupation – taking the notion of occupation into indoor spaces which could be useful in and of themselves for meetings and mitigating the oncoming cold of winter and taking direct action against foreclosures.

However, a number of critics weighed in on the particulars of the execution of the occupation. These critiques have centered on the following. 1) There were objections to the spirit of the occupation, which seemed to some too much like a dance party or an “anarchist photo op” rather than a serious attempt to reclaim a space. 2) There were questions about process; why was a second occupation initiated by a small-ish autonomous group rather than voted on by a general assembly? 3) There were questions about timing and tactics. Why the middle of the night, after our greatest numbers had dissipated? Did the occupiers flee the scene without a serious effort to hold the space? There were debates over the burning and defense of barricades. Defenders of the occupation point out that burning barricades help to dissipate teargas to some extent (though bonfires also up the ante of what seems like a street fight, so the net impact of this tactic is unclear). It’s not clear that anything could have held the space given hundreds of riot cops, save a crowd of thousands which at that point we did not have.

An open letter from a medic criticizes the tactics used during the abortive occupation of the Travellers’ Aid Society Building.

An open letter from a medic criticizes the tactics used during the abortive occupation of the Travellers’ Aid Society Building.

My concern was with the ill-conceived tactics used to occupy the building, in that it looked like an anarchist glamorshot instead of a committed and revolutionary act to actually acquire and hold that space. I am tired of direct actions being done in a way that turns them into photo-ops and nothing else. I am tired of watching barricades be built only to be abandoned the minute the cops open fire. In addition, the crowd on 16th around the occupied building was terrifying far before the cops ever showed up. As a woman and queer person I wanted to get the fuck out of there almost immediately as it felt wildly unsafe on multiple levels, and I feel like whoever orchestrated the take-over made choices that specifically facilitated the overall crazy atmosphere. There were fistfights, screaming matches, fires, and just a general vibe that people were out to fuck shit up, and absolutely no attempt on the part of anyone to shut that sort of in-group violence down.

Zunguzungu offers a nuanced account of the day, including his take on the 520-16th St. occupation. (His collection of links is also quite good, and I found a couple of less-circulated pieces through him.)

We do things in the open, or I’m not part of that “we.” If we believe in direct democracy, then don’t we have to be honest about the fact that this decision was not made in that way, and that it is now reflecting back on the entirety of Occupy Oakland and yesterday’s strike? A lot of people who joined yesterday, and who were energized by the port action, are going to feel alienated by what happened, which weakens the movement (to say the least). And I wasn’t there last night because I didn’t know it was coming; I honestly don’t know yet what I think about that decision because I was never given the chance to think about it. Perhaps I might have been swayed by the arguments made in its favor, and perhaps I might have been there last night to protect the space from being re-taken by police, as it eventually was. But I wasn’t there last night, nor were the majority of us. By acting on their own, the people who made that decision prevented the rest of us from taking part in it, and while you may only see this as a tactical error — decisions made by only a small group will only command small support — it is a real problem, as was shown last night.

Counterposed to these critiques, it’s worth reading the statement on the occupation of the former Travelers’ Aid Society posted on Indybay and the original communique read after the building was opened.

3) Calls to “Expel the Anarchists” or Exert Tactical Cohesion in the Movement

Initially, a number of calls bounced around Facebook to “expel” people engaged in property damage. Most of these seem to have gotten refined or dropped given widespread opposition, but there still seems to be a good deal of support for a proposal to cohere the tactics of the movement, refusing an absolute standard of “diversity of tactics.”

This proposal is a call for specific answers to three basic questions regarding Occupy Oakland’s potential official recognition and acceptance of Diversity of Tactics:

- What tactics are going to be explicitly excluded? (For instance, will throwing projectiles, molotov cocktails, setting fires, etc. be rejected?)

- How will we actually prevent the rejected tactics and behaviors from happening?

- If rejected tactics happen anyway, how should we distance ourselves from them?

As of this writing, there is also talk of “Non-Violent Occupy Oakland” breaking away and forming a separate occupation.

4) Rejoinders, Defending the Role of Anarchists in the Movement, Contextualizing and Partially Defending Property Destruction, etc.

This “baiting” of “anarchists” in the movement elicited a number of strong replies. Many defended the role of anarchists, observing that anarchist organizers and anarchist organizational principles have been central to this movement since its inception. Most criticized the role of pacifist “peace police” who seemed to want to control the movement, perhaps even enacting their own kind of violence on others who refused their ideas. Others promoted accepting a diversity of tactics being employed by autonomous groups at major events. Still others contextualized and partially or wholly defended property damage as part of the strike.

My friend Katie Woolsey takes issue with the tendency label “anarchists” and “the Black Bloc” as problematic categories and to treat them as “outsiders,” whether geographically (the trope of “outside agitators, not even from Oakland”) or as ideological outsiders. Further, where some of the authors above criticize the Black Bloc for intensifying risks that not everyone is willing or able to accept, Woolsey sees the positive side of that willingness to accept risk.

The folks who are being derided as “anarchists” and “black bloc” kids are the most brave and generous of the movement. They are willing to use their bodies to carry out the general will. You cannot say that this is not so. The Oakland commune has already, previously, voted to expand to indoor spaces. Reclaiming derelict and foreclosed properties is not only the will of the Occupy movement, not only written into its very NAME, but is in practical terms the only way that the movement will be able to hold through the winter without reducing itself to only the hardiest and most able-bodied among us, the most willing to sacrifice personal health and comfort. (And guess who those tend to be?)

Voyou argues that worries about property destruction due to its media impact or its effect on police violence reflect a desire for control which is ultimately an elusive possibility.

Voyou argues that worries about property destruction due to its media impact or its effect on police violence reflect a desire for control which is ultimately an elusive possibility.

As reclaimuc put it on Twitter, “the media will always be terrible, no matter what we do.” This is even more true of the idea that property damage “provokes” the police, which really badly misunderstands the way in which public order policing works….

In both cases, the liberal position is based around a belief that we can control how we are perceived, and how the state (and its ideological apparatuses like the media) will respond to us. Or actually this could be put more strongly: the criticism reveals the liberal’s desperate need to be in control. The fact that protestors have very limited ability to prevent state crackdowns, and certainly individual protestors can do almost nothing, is scary, and it conflicts with deeply held liberal beliefs about how the state works, and how protesting can change it.

Reclaim UC contextualizes the debate, reminding us that the Occupy Oakland general assembly approved statements respecting a diversity of tactics, encouraging autonomous actions, and offering support for building occupations.

An interesting question has been raised about the meaning of “neighborhood” or “autonomous” building occupations and likewise what “community” is being referred to in the context of “community needs.” Who is this collective “we”? Who falls outside of that category? For an action to be “autonomous” or be associated with a “neighborhood” does that mean it can’t be an official part of the GA or of the so-called Occupy movement?

Emily Brissette makes a case for embracing a diversity of tactics as part of the potential of the movement, rejecting simplistic calls to “be peaceful.”

But we must create space for a diversity of tactics—not, as some have suggested, as code for the legitimation of violence—but as a necessary corollary to the diversity of this movement itself. We must find a way to harmonize our myriad voices—not by silencing some, but by giving each its range of expression. We must accept that social transformation will entail conflict, that we won’t always be embraced by our audiences (even those in whose name we speak), and welcome the personal and collective growth that conflict can engender. We must, in short, recognize the power we wield in our capacity for disruption, and let go of our fear.

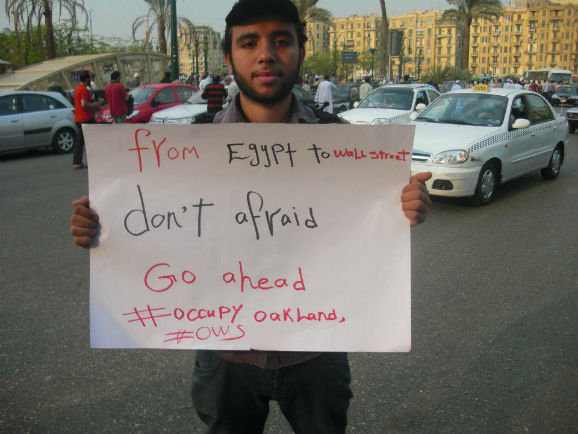

Another Indybay poster puts the question in a global perspective.

Is it correct to call defense of our direct-democracy,our autonomy, our communities, and bodies senseless, and violent? Is it OK to attack the legitimacy of the countless struggles that have chosen to do this? Were individuals on the Nile bridge (Egypt) whom, literally, fought off police attacks senseless? Were the Argentinians resisting the ruling classes in 2001 by combating police attempts to violently remove them from the city center by charging down riot squads, senseless? Are the Greek anti-austerity mass gatherings and ‘occupy Athens’ senseless for doing the same?

Many posts defend the diversity of tactics and the right to damage property as an autonomous tactic without making any claims that it is a good or necessary tactic; many posts also carefully differentiate between violence and property damage. Lilprole takes a different approach, seeing violence as an objective part of revolutionary struggle and putting property damage in the context of a need for self-defense against state violence. The piece continues, later, to answer many of the objections to property destruction in the general strike raised in the first section.

In a revolutionary struggle, there will be violence. The state is violent and it will use violence to destroy threats to it. It will protect the property and capital of the economy. We must defend ourselves against this attack and be able to defend our movement. In this struggle people will engage the police as well as the property of their enemies. More and more, people are going to break the law in large groups. They will go on strike largely without union support, occupy their workplaces, students will walkout of school and occupy them, people will expropriate goods from businesses, and people will engage with the police. These are all things that have already happened, in this and other struggles, and will continue to happen as part of a revolutionary struggle against capitalism.

5) What’s Next?

It’s a little bit artificial to separate these pieces into different categories, but now that the initial furore has worn down a bit, a number of pieces have come out which, while continuing to address these debates, place more of the emphasis on next steps, either for the national movement or for Occupy Oakland in particular.

Mike King argues against the scapegoating of radicals in the movement, seeing the objective dynamics of social crisis as contributing to the developments of the Occupy movement.

Wednesday night’s occupation of a former homeless clinic that surely wasn’t closed for lack of need, located around the corner from Oscar Grant Plaza, is likely the first of many occupations in Oakland. The General Assembly passed a proposal that calls for the occupation of vacant housing and buildings. This country is full of foreclosed homes with people living in the streets or in their family members’ basements or on a friend’s couch; closed schools or under-funded schools and kids without hope; and empty factories whose disconnected workers are on the streets or in a cell. The public outcry for radical social change is no longer just a want but a need. It is no longer held by the few, but by the many. This many is steadily expanding what seems possible. The ascending nature of the movement and the fact that its ambitions have always been explicitly radical provides hope that it will overcome internal divisions and attempts to sow confusion and contention. Wednesday’s actions were a success. We have a choice to either overcome the differences that have arisen in this moment through even-handed debate, collective action and solidarity or we can let those differences divide and destroy us.

Asad Haider offered an early and thorough account of the day’s activities and an assessment, arguing that we should set aside property destruction as a tactic, focusing instead on mass, militant forms of occupation.

We are at a moment when occupations are seriously considering an expansion of strategies. Everything in this movement points to the occupation of spaces that are in a state of disuse caused by foreclosure and budget cuts. The state is attempting to delude you into thinking that it uses violence to prevent destruction. Do not let them mislead you. Last night it used violence to prevent the production of a new space….

I suggest refusing to blame Oakland, but simultaneously shelving property destruction as a tactic. The police didn’t care about it. The banks have money to repair their windows. What threatened the state was the creative restoration of the city. Imagine a strength that could force the state to retreat: a mass movement that walks out of work and occupies everything.

Gayge Operaista offers several ideas for how to move forward:

A way to accomplish the expropriation of buildings needs to occur, as it is not only both one of the most likely path to speed up the process of communization, but, the logical action to take as the rainy season sets in. The Travelers’ Aid Society occupiers certainly had the right idea, even if they were unable to defend their gains against a police response of unforeseen magnitude.

While the majority feel of the participants during the General Strike was that capitalism is broken, the start of recuperation is already there – into a recall campaign against Mayor Quan, and into making other reformist demands. We need to learn from Madison and other struggles how this recuperation occurs and to struggle against it.

Occupy Oakland needs to better address issues around race and gender. While the camp is exceptionally diverse, the General Assembly too often centers the voices and concerns of white men, and then, following that, men in general. The Feminist Bloc grew out of a Women and Trans and Queer group, and hopefully from there, we can broaden the discourse to include reproductive labor, sex work, and domestic work, as well as the hyperexploitation and oppression of queers and trans people under capitalism.

We need to avoid aiming for a unified message or cohesion. The main strength of the Oakland General Strike was that it was the Multitude coming together and struggling in common, individuals and groups with their own experiences and their own personal position realizing common needs and goals. Trying to form a unified vision or demands for Occupy Oakland, rather than the fulfillment of its members’ needs and wants by expropriation and direct conflict with capital will doom it to both a counterrevolutionary character and to fail to ever regain anything resembling the energy of November 2nd.

Salar Mohandesi asks whether Occupy Oakland has now become a model for the Occupy movement nationally, concluding that there’s something problematic in that approach.

There is a tendency that will argue that the best way to deepen the movement here would be to do exactly what they did in Oakland: brace for a spectacular confrontation that might ultimately advance the movement further. The strategy is simple, teleological, formulaic: if we wait until the November 15 eviction, then there will be a confrontation; if there is a confrontation, then we can gather more support; if we have more support, then we can be like Oakland. Though it’s certainly not the only sentiment, it does seem to be gaining some ground. There is talk at Occupy Philly about “fortifying” the occupation in anticipation of a crackdown….

To look to Oakland for inspiration is one thing; to fetishize it into an immutable paradigm is quite another.

Don’t tell the folks in Dallas, who are moving ahead with plans for a general strike there.

6) Miscellaneous

Jaime Omar Yassin writes about the way in which the buildup to the general strike and the activities of the day itself transformed consciousness in Oakland.

Words fail, I was simply moved by the reality of all these people coming down to engage in an ‘illegal’ action that just a week ago would have been considered radical and subversive, but today was filled with happiness, community, respect and love. And the power of such a mobilization to silence and dispel the police, the power of people to write the rules of public space. That’s something I’d never thought I’d see in my lifetime.

He also has a couple of good pieces criticizing mainstream media coverage of the strike and characterizing the occupation for a hearing at City Hall.

Brad Johnson relates the feeling of there being something ineffable about the day.

Labor Notes covers the day from a union perspective.

Reclaim UC puts the general strike into perspective on a timeline, going back to the death of Oscar Grant and the community response that ensued.

Concluding thoughts

Where does this review of a messy debate leave us? What’s interesting about this moment is that the movement is vital enough that calls to exclude groups of activists or split the movement are meeting a good deal of resistance. There seems to be a fairly broad consensus about finding ways to work together. There probably does need to be some middle ground between “anything goes” in terms of diversity of tactics at every action and an expectation that all tactics will be democratically decided by a general assembly. We need to be able to talk to each other about tactics, instead of refusing the conversation or threatening to call the cops on activists who get out of line. The latter extreme is very unrealistic, and the former extreme risks creating a situation in which the movement narrows to those who are willing to confront the police, usually a dwindling number. At the same time, advocates of “non-violence” have sometime put forth their demands using a form of common sense which turns out to be pretty ahistorical. Most social uprisings are messy and involve a wide range of actions, from deliberate praxis carried out collectively to direct action of small groups to spontaneous, sometimes seemingly “illogical” outpourings that usually seem out of step with reality but very rarely have the gift of addressing the spirit of the moment in a way that no plan executed by a steering committee could. Advocating only this kind of pure propaganda of the deed is surely a recipe for burnout and isolation, but imagining a movement where all tactics are submitted to central control probably involves a fallacy similar to the one described by the Voyou piece above.

What is the way forward? As the piece asking whether Occupy Oakland is a model for Occupy Philly suggests, there’s no easy answer. The good news is that each occupation around the country is potentially a site for innovation and experimentation. A wave of city-by-city general strikes, even if they don’t quite conform to the old notion of a general strike? A wave of building occupations? Let 99 flowers blossom and let 99 schools of thought contend amongst the 99 percent! (The 100th, which I take it would be subsuming the occupations into lobbying or campaigning for Obama, should be rigorously exposed as the escape clause for the 1% that it is.)

Comments

4 responses to “After the Oakland General Strike, tactical debates emerge: Let 99 Flowers Blossom”

Hi Binh,

Good to have you commenting here. I agree with your assessment of the TAS action: not bad in principle or strategy, but tactically disastrous. Unfortunately the shitstorm that followed has tilted the debate in a direction where that level of discussion becomes difficult and it’s a binary “Do you defend or attack the TAS occupation?” deal. A well planned, overnight occupation of the kind you describe that could gone public the following morning, when larger crowds could have defended it, would have moved things forward and potentially overshadowed the Black Bloc foolishness earlier in the day rather than being linked to it. (Adam would know better than me, but I believe the folks behind TAS were not, strictly speaking, the same crew that had trashed Whole Foods and the banks earlier that day).

Probably the overall forward-moving dynamic of Occupy Oakland and the whole movement will overshadow the errors that were made and provide time and space for further efforts (similarly to an earlier well-publicized screwup when John Lewis was symbolically shunned by Occupy Atlanta; subsequent evolution of the occupation there has made that mostly irrelevant now).

I think there’s a similar stubbornness in many occupations that you point out with Philly: many participants view the physical occupation, including details like the exact space that was originally chosen, as a “line in the sand” and are preoccupied (no pun intended) with holding it rather than giving a little to flexibility. Many of these dynamics are very similar to what those of us in Wisconsin this past February were able to observe with the nearly sacred role of the Capitol occupation in the movement there.

Finally someone on the socialist left who is talking about the sharp debates within the anarchist movement about this! In the 90s, there was very little difference of opinion in their camp on these types of actions because of “diversity of tactics.” Now that we have a real mass movement, the calculus has changed; a lot of people feel (rightly) that if we screw this up, we, the 99%, are royally screwed for a long time to come, hence the impassioned tone of the debates.

I was glad to see the author did not take up Todd Chretien’s argument in Socialist Worker that the Traveler’s Aid Society (TAS) takeover was a mistake because it didn’t go through the General Assembly. The fact of the matter is that is not how this movement works — autonomous groups call their own actions, and occupiers get on board (or not). If every smallish group with their own idea for an action has to get G.A. approval it will never happen and G.A.s will become even more of a bureaucratic nightmare than they already are.

The problem with the TAS action was: 1) they didn’t sneak into the building and begin building fortifications inside to truly occupy and hold the space 2) after taking the building, they set up (ineffective) barricades on the street in front of the place, and then set them on fire, attracting police attention and 3) they got a lot of people outside the “Black Bloc” involved in an exciting action that was ill conceived, poorly executed, and an avoidable failure (they didn’t keep the space). I suspect this was the first time the planners had ever tried to seize a building, so some of these mistakes were due to inexperience, which is unavoidable (the only folks who don’t make mistakes are the people who don’t do anything or take any action).

Now, this business with Occupy Philadelphia “fortifying their encampment” is a bit much. The city has a million dollar construction project scheduled to take place there in a week or two, something planned years in advance, that will create JOBS for construction workers, and the Philly G.A. is vowing to stay put no matter what. This runs the risk of re-creating the activists vs. hard hats divide that plagued the 60s movement. The sad thing is there is a park very close by where they could move the occupation to continue the movement. Instead, it looks like they are going to get involved in a counterproductive and foolish conflict with the city and possibly the unions because they are too inflexible to move a couple hundred feet.

I don’t have time to write a more detailed response, but this article was incredibly timely and helpful, Adam. I’ve really been having trouble sorting out my ideas about this, and feel much clearer after reading this.

From what I can gather from many other “Occupy” sites, there are similar conversations going on around the country – but of course not as developed, because the level of activity is lower and there are not the well developed political trends found in the Bay Area.

Not being from there, I wonder how much of this debate has picked up where discussions from the 2009 student movement left off? Or are there entirely new players in important roles now?

It’s also important to note that there are at least a few infiltrators in the Black Bloc although, I agree, that’s not entirely the case – there’s a sizable number of people who actually promote these politics: