Posted July 13, 2011

By Dan La Botz

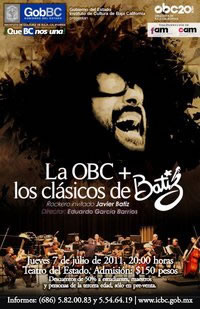

Javier Batiz, the great Mexican rock-and-roll guitarist, played and sang last week in a concert that embodied and gave voice to everything that is most wonderful about Tijuana and the U.S.-Mexico border region. Batiz, who since he was thirteen played in the bars and nightclubs of Tijuana, performed this time with the Baja California Orchestra (OBC) before a sell-out crowd of 1,100 in the auditorium of Tijuana’s Center of Musical Arts in a concert that sometimes contrasted, sometimes juxtaposed and occasionally synthesized the styles of blues, rock, jazz and classical music. This is the Tijuana that most Americans don’t know, the border—where I grew up—that represents not a political wall that divides peoples and cultures, but two-way cultural bridge that unites them.

Javier Batiz, the great Mexican rock-and-roll guitarist, played and sang last week in a concert that embodied and gave voice to everything that is most wonderful about Tijuana and the U.S.-Mexico border region. Batiz, who since he was thirteen played in the bars and nightclubs of Tijuana, performed this time with the Baja California Orchestra (OBC) before a sell-out crowd of 1,100 in the auditorium of Tijuana’s Center of Musical Arts in a concert that sometimes contrasted, sometimes juxtaposed and occasionally synthesized the styles of blues, rock, jazz and classical music. This is the Tijuana that most Americans don’t know, the border—where I grew up—that represents not a political wall that divides peoples and cultures, but two-way cultural bridge that unites them.

Batiz’s concert exemplified the bicultural world of the border—or perhaps better tricultural, for in addition to the Mexican and the American, the border has its own culture as well. Batiz performed favorites from his repertoire of blues, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll, song both by others and of his own composition, from the traditional “House of the Rising Sun” (the Spanish version), to Otis Redding and Jerry Butler’s “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long,” to his own “Montañas.” Listening to Batiz run up and down the neck his electric guitar with the greatest virtuosity one could hear echoes of Jimmy Hendrix and B.B. King, but also infusing it all Batiz’s own highly personal and passionate style.

Echoes and Resonances

Germán “Tin Tan” Valdés

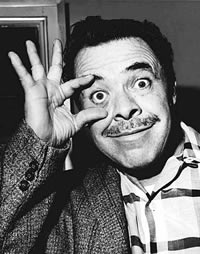

There were so many cultural resonances in Batiz’s performance from so many quarters, not only the great African American blues and rock musicians, but also the great Mexican performers. While the orchestra and the members of Batiz’s band who played with them were dressed in black, Batiz himself was dressed all in white and wearing a calf-length, sleeveless vest. One could not help but be reminded of the great northern border performer Tin Tan (Germán Valdés) of Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, dressed in pachuco style with his zoot suit, an artist whose tremendous musical talent, sharp wit, and audacious in-your-face style first validated the border culture and its pocho Spanish in the 1940s.

While playing his guitar Batiz has all the authority and presence of a great artist, but between numbers he is the club entertainer who minces about the stage, bent over, shouting out challenges or making jokes sotto voce to the audience, and one cannot help but think for a moment of Cantínflas (Fortino Mario Alfonso Moreno Reyes), the actor whose great films of the 1940s, 50s, and 60s portrayed the experiences of those millions of Mexican peasant migrants to Mexico City and the other growing cities of Mexico (including Tijuana) with all of their struggles, hopes, and anxieties. And, of course, once we have Cantínflas in our minds we cannot help but think of Charlie Chaplin. So, if you are an Anglo, imagine Charlie Chaplin on stage playing the guitar like Jimmy Hendrix and you will have an inkling of what this concert was like.

Then, in one of the marvelous juxtapositions of this concert Batiz paused and conductor Eduardo García Barrios and the OBC played Igor Stravinsky’s “Ragtime for Eleven Instruments” (1917-1918). Who better than the Russian-French-American Stravinsky to exemplify cross-cultural synthesis and what better piece than “Ragtime” with its combination of classical, jazz and the emerging new music of early twentieth century in the Europe of war and revolution. And then back to Batiz again, the vato of the border, sometimes playing with his own back-up band—José Villa on bass and Ramón Cortéz or wife Claudia Madrid on drums—or sometimes backed up by the 20-piece OBC, something like Ray Charles in those records of the 1960s. What a concert, and where else but Tijuana?

Tijuana

We might think of the diversity and multiculturalism of Tijuana as something particularly modern, the result of globalization, mass migration, and the communications revolution, but of course, multiculturalism as old as humanity itself. The Kumeyaay (Kumiai or as the Spaniards called them Digueño) people, descendants of the Asians who had migrated across the Bering straits thousands of years before, were living in Baja California when Cortéz crossed the gulf that bears his name to invade their territory. Later, from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries, most of Baja’s inhabitants migrated from the neighboring state of Sonora. Tijuana, the isolated little border town of a few hundred at the turn of the last century and virtually inaccessible from Central Mexico until the 1950s, grew up into a modern metropolis as an extension of the economic power of the United States. The U.S. Navy’s early decision in the 1910s to expand its facilities in San Diego, making it one of the important ports of the Pacific Fleet, led to the growth of San Diego and also therefore to the growth of Tijuana. Los Angeles area businessmen and racketeers first invested in Tijuana, constructing the racetracks, bars and bordellos that served American tourists. By 1928 work had begun on the great Agua Caliente Hotel and Casino and then shortly afterwards the Agua Caliente Race Track, attracting thousands of tourists from San Diego and Los Angeles.

Many of those who worked in the Tijuana clubs were Eastern European Jews who had migrated first to New York City where they worked in Vaudeville, then to Hollywood to get into the movies, and, when that failed, moved on to Tijuana where they became the singers, dancers, and comedians on the stages of the city’s clubs. Not surprising, then, that one of Tijuana’s oldest neighborhoods is the barrio Dinnerstein. Entertainers from England, France and Spain sometimes trod the boards in Tijuana too. In those early days Mexicans weren’t allowed to work in the city’s nightclubs and bars, except in the most menial positions. As historian Jorge Bustamante has noted, the musicians and other hotel and restaurant workers formed unions in the 1930s first to demand the right to perform on stage and then to fight for housing, leading to the construction of Colonia Libertad. Chinese immigrants, who had been in northern Mexico since the late nineteenth century, migrated from Chihuahua to set up their shop in Tijuana.

Spaniards, mestizos, the indigenous, Americans, Chinese, and Eastern European Jews who immigrated in the 1910s and 1920s formed Tijuana’s population until the 1930s. During that same period, millions of Mexicans had migrated to work in the United States, mostly in the fields of the Southwest, but also in the steel mills of Chicago and on the Pennsylvania Railroad. With the coming of the Great Depression, local police and social workers and ordinary Americans drove 500,000 Mexican immigrants from their homes and communities, sending them by railroad back to Mexico. Many of them, waiting for a change in the economy and in American attitudes, decided to stay on the border, in Tijuana. So the city was filled with Mexicans who had lived in the United States, many of whom spoke English.

The Condes of Tijuana

I was invited to the concert by my friend Lucila Conde, whose brother, Jorge Conde, would be singing with Batiz in the concert. The Condes grew up in the old downtown of Tijuana, where their family had a jewelry shop, the Central de Joyas. The parents, Jorge Guillermo Conde Otáñes and Laura Mabel Zambada Valdez, had met because of their common interest in music. Laura Mabel was a singer in the Follies Vergier and for the Mexico City radio station XEW, “The Voice of Latin America,” which in the 1930s, 40s and 50s presented the most talented musicians and singers to audiences in Mexico and beyond. Jorge, Sr. was a travel agent and musical composer, who followed his wife on her tours throughout Mexico as together they wrote music. Two of their most famous songs, “El sapito” recorded by the Hermanos Reyes and “El mahometano” recorded by Fernando Rosas, achieved national recognition. Not surprising then that some of their children would have an interest in music. Their daughter Rosina Conde, poet and novelist, often gives reading of her work where she also sings ballads and boleros, and Jorge Conde, Jr. has since he turned 50 begun to sing with Batiz.

My friend Jorge came on stage in the middle of the concert to sing, performing the Doc Pomus (Jerome Solon Felder) song “Lonely Avenue,” which became a great Ray Charles hit in 1956. Jorge was in his element, singing in the style of Charles’ soft and sexy blues, swaying and snapping his fingers to the heavy beat of the drum and base and backed up by a three young singers. Batiz meanwhile could not be kept on the stage but migrated toward his public. Ignoring the conductor, he wandered off stage, down the stairs, into the front row to get close to the customers, so to speak, the club entertainer in his element.

Before the concert, Lucila and I, and her two daughters, Maya and Marlies, went by Jorge’s house, a modern little apartment at the foot of Cerro Colorado in the outskirts of Tijuana. Jorge had cut his hand while trimming a bougainvillea in the backyard and was trying to staunch the bleeding while his wife Jitka ironed her dress and Jorge’s shirt, and supervised the dressing of their daughters Tamara and Laura in preparation for the concert. Once the ironing was done, amidst the domestic hubbub, Lucila, Jorge, Jitka and I sipped becherovka, the Czech liqueur. Jorge met his wife, Jitka Crhová, when they were both working as interpreters at a political meeting in Europe. In 1992 Jitka, a polyglot who speaks her native Czech, Spanish, English, Russian fluently and has studied several other languages as well (and holds a Ph.D. in linguistics) took a position as a professor of modern languages at the University of Baja California. Together, Jorge, Jitka and their children may be said to represent one part of that Tijuana that most Americans don’t know, a highly educated and cultured middle class that arose in the late twentieth century as a result of the growth of commerce and industry on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Batiz’s Tijuana

When in 1965 the United States ended the Bracero Program that had brought millions of workers to labor in American fields since the 1940s, Mexico and the United States agreed to create a tax-free industrial zone along the border. U.S. corporations saw an opportunity for cheap labor and Mexico the opportunity for economic development and jobs for its burgeoning population. By the 1970s construction began on what would eventually be hundreds of industrial plants called maquiladoras that stretched along the Mexican border from the Gulf to the Pacific, employing over one million workers. The creation of the maquiladora zone would lead to an influx of hundreds of thousands of people to the border region, swelling its cities, and above all Tijuana. The growth in population and the economic importance of the border transformed it as infrastructure was created: not only highways and industrial parks, but also colleges and universities. Tijuana became not only a magnet for peasants seeking better paying jobs in factories in the city, but also for managers, technicians, and professionals working either in industry or for the government. Together the mangers and industrial laborers, the professionals and the new service workers transformed the little border town of Tijuana into a modern city.

Batiz grew up with Tijuana, playing for its expanding and youthful population. In 1954, when Batiz began playing, Tijuana had about 75,000 inhabitants, while today it has almost two million with five million in the metropolitan area stretching from Tijuana to Mexicali to Ensenada. The centers of Tijuana then, back in the 1940s and 60s, were the tourist strip of bars and trinket shops on Avenida Revolución and the Mexican business shopping district on Avenida Constitución. The American middle class and working families who shopped by day on Revolución never wandered over to the next block where the Mexicans worked or into the neighborhoods where they lived. Wealthier Americans made it to the Agua Caliente Race Track and to the nightclubs and better restaurants, but theirs too was a quite limited picture of Tijuana. The U.S. sailors and marines who frequented the bars and brothels stumbled drunk back across the border, and then back to the base. They never knew another Mexico. All of those groups at different moments formed parts of Javier Batiz’s audiences, they and Tijuana’s cosmopolitan population of mestizo and indigenous immigrants from all over the country as well as immigrants from China, the United States, and Europe. (My favorite example of cultural and linguistic synthesis in that era was the Nuevo Kentucky Chinese Restaurant on Avenida Revolución.) Like rock and roll everywhere, Batiz’s was the music of youth, working class and middle class youth, alienated from the old music and the old values of their parents, the youth who came of age with it, and are now Batiz’s age (and mine), or who grew up into it and now, underage, sneak into the clubs to hear it.

Batiz’s town, Tijuana, has not had an easy time of it. For years, Tijuana’s residents lived with the stigma that their city was the vice-district for the U.S. servicemen. Tijuana was beleaguered. Americans simultaneously exploited Tijuana and condemned it as an open city where anything goes. Mexicans from Mexico City and Central Mexico denigrated the North of Mexico as the place where culture ends and the barbecues begin (Donde termina la cultura y empieza la carne azada.) The border was held in especially low esteem by Mexicans as region of crime and corruption, moral decay and social degradation. Americans ridiculed border residents for speaking Spanglish and Mexicans condemned them for speaking pocho.

For decades Tijuana was the stepping off point for undocumented immigrants crossing into the United States until the border walls drove them further East into Arizona’s dangerous deserts. More recently, Tijuana, like other border cities, has suffered both from the powerful drug lords and from President Felipe Calderón’s war against them in which 40,000 have died, dozens of those in Tijuana. No wonder then that when in the midst of the concert Batiz paused to tell the audience how proud he was to play before “my beloved and beautiful Tijuana,” for which he had written the song “Montañas,” the audience, pleased for once to hear their beleaguered city spoke of in such tender loving words by one of its great cultural icons, cheered and applauded.

What a presence, what an entertainer Batiz is, with his great head of kinky black hair at shoulder length, his thick Zapata mustache and scraggly beard, his great toothy smile, alternately the proud artist and the self-deprecating comic. At one point during the concert Batiz paused and said that this a great time for him, “I am 67 years old, and,” gesturing to his wife, Claudia Madrid, “married for 30 years, and have been performing on stage for 54 years.” At the age of 16, in 1957 Batiz created his first rock-and-roll band, “Los TJ’s con Javier,” founding Mexico’s rock-and-roll movement. By 1968 Batiz was playing in the Terraza Casino in Mexico City’s Zona Rosa, which during those same years hosted other stars such as Jim Morrison of the Doors. Batiz served as teacher and example to players such as Carlos Santana and Fito de la Parra of Canned Heat. Most recently he was honored with the Creador Emerito 2011 by the Mexican National Council for Culture and the Arts. He is the subject of a forth-coming documentary by Francisco Javier Padilla with the title “El Brujo,” (the Black Magician), so-called because of Batiz’s magical playing style.

The concert, which had been punctuated throughout by applause, culminated in an uproarious standing ovation and cries of “¡Bravo!” and “¡Otra!” Like the others, I felt proud when Batiz spoke about his “beautiful and beloved” Tijuana, proud to have grown up on this border, even if a mile or two north of it. With all of the reports of the violent drug wars, the killings and kidnapping, the Mexican Army’s violation of human rights, and the rest of it, it was wonderful to experience this concert, an apotheosis of the border’s great musical culture.