Posted April 14, 2011

Ten years ago, after the police killing of a teenager named Timothy Thomas, Cincinnati erupted in what some called vicious riots and others a righteous rebellion. The uprising over a string of police killings of black men made Cincinnati the subject of a national discussion that took place from the pages of the NAACP’s The Crisis and The New York Times to NPR and Nightline. Cincinnati became synonymous in the public mind with racism and bigotry and the reputation lived on for years. Living down that reputation became the goal of City Hall and local business interests who worked to put the matter behind them, burying both the racism and the violence under the magnificent façade of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center and drowning out the lingering shouts of pain and protest with jazz, blues and country musical festivals on the riverfront. For the African American community and for many other Cincinnati residents, the real issue has been to confront racism, to challenge the ruling elite’s power, to raise consciousness, transform structures, and shift power. We are still working at it.

The immediate cause of the rebellion was a police shooting of an African American man; for the black community it was the last straw after a series of such killings and after years and even decades of police racism and violence. The injustice of the criminal justice system, however, represented only one aspect of the African American community’s experience of racism which also extended to social segregation, economic exclusion, and widespread alienation from the political system. Out of anger and indignation young African Americans rose up in an angry ghetto uprising, while other black and white activists joined together in political protests and a boycott of the city. Altogether the movements and protests of that year would change the city, result in a new political culture of criticism, dissent, and protest. And Cincinnati would be better for it.

Other recent accounts of the last decade on television and in the local newspaper have discussed the “riots” but have largely ignored or downplayed the role of the Black United Front, the March for Justice and the boycott of the city. Most of the major media have tended to self-congratulation on progress made rather than on a serious examination of the state of the city. This account is meant to challenge and correct those accounts.

Returning to these issues today raises many questions. Where are we today, a decade later? What did we learn from the events that led to the rebellion of 2001? What did we learn from the rebellion, the protests, and the boycott that followed? What was the political upshot of all of those events? And how has Cincinnati changed? Have police-community relations improved? Are Cincinnatians better off—or worse off—today than they were then? Have relations between whites, African Americans and other ethnicities improved? Is our city making progress? What can we do to make it a better place?

Before even turning to the events that took place in that period, it should be noted that the Black United Front represented the most important force for change in Cincinnati in this period. Rev. Damon Lynch III, the pastor of New Prospect Baptist Church in Over-the-Rhine, founded the Front and served as its president at the time. While Lynch himself might be described politically as a liberal, many of the Front’s members were admirers of Marcus Garvey and his black nationalist politics inspired the group. With the NAACP failing to provide leadership on race issues at that time, the Front fulfilled the role usually played by that organization and other traditional civil rights groups. It was the Front that picketed restaurants downtown for their racist exclusion of African American diners in 2000, returning to the tactics that had been used in Cincinnati in the 1940s and 1960s. It was the Front and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) which brought the lawsuit against the city before Timothy Thomas was killed that later resulted in the Collaborative Agreement. It was the Front and Lynch who a year before the uprising spread the word throughout the black community that the Cincinnati Police’s killing of black men was wrong and had to stop. Lynch’s New Prospect church held the funeral for Thomas. Lynch became the face and voice of the black community both in Cincinnati newspapers and on ABC’s Nightline. A few Front activists, overcoming the opposition of the more militant black nationalists in the group, became the link between the Front and the March for Justice.[1] And it was the Front and the March which sparked the boycott of Cincinnati. At every crucial moment of the struggle in 2000 and 2001, the Black United Front was in the lead.

THE FACTS: WHAT HAPPENED IN 2001?

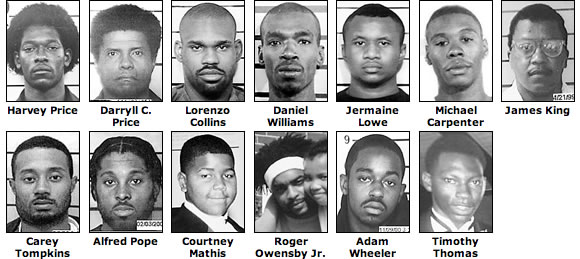

Cincinnati exploded in protest and rebellion in April and May of 2001 following the April 7 police killing of 19-year old Timothy Thomas, the fifteenth African American man under the age of 50 to be killed by the police between 1995 and 2001.[2] While several of those killed had drawn guns and shot at or shot civilians or police, others did not have fire arms or were killed while in police custody. Thomas, who had committed many misdemeanors and had several warrants for his arrest (but who had no record of violence) was nevertheless chased into an alley, shot and killed by a police officer. Thomas’s mother Angela Leisure showed up at City Hall accompanied by 200 other community members, almost all of them black, to demand that city and police officials explain why her son had been killed, but police and politicians dealt with her contemptuously.

Furious with the killing and the contempt, an angry crowd left City Hall and went across the street to the First District Police Station where they demonstrated and held impromptu interviews with the media. As night fell they marched into Over-the-Rhine, the inner city ghetto since made famous by the film Traffic, there word spread and the neighborhood seethed. When on the following day peaceful protestors attempted to march out of Over-the-Rhine and into the downtown district carrying signs with slogans such as “Stop Killing Us,” police prevented them, frustrations grew, and violence followed.

During the four days of rioting in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood that followed, windows of businesses were broken, stores were looted, fires were set, and people simply passing through the area were attacked.[3] Mayor Charlie Luken issued a curfew order that lasted two days, but it was generally only enforced in the inner city African American communities and downtown, while Mt. Adams entertainment district catering to well-heeled whites stayed open. The riots caused an estimated $3.6 million in property damage, much of it on the Main Street entertainment district, and 63 of those arrested were indicted on felony charges. Most of those charged with looting were not from Cincinnati. The Cincinnati rebellion of 2001 was the largest disturbance in the city since the ghetto rebellion of 1967 and the largest in the United States since Los Angeles riots of 1992 which began with the police beating of an African American man named Rodney King.

Police Shoot Mourners at Funeral

Many white Cincinnatians and suburbanites expressed surprise at the events. African Americans living in the city wondered why things had not blown up sooner. In workplaces and restaurants around the city there was a common conversation: White folks asked, “Why didn’t he stop?” when a policeman told him to, while black folks told stories of how they had stopped and been insulted and roughed up, and sometimes beaten and falsely charged, arrested and jailed.[4] For black Cincinnatians, the killing of Thomas and the other 14 black men represented only the most recent events in a decades-long history of police racism and violence. The Black United Front and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) had been working together for some time before Thomas’ killing to find the legal means to restrain the Cincinnati police. Yet even African Americans, cynical as they were about the city, were shocked by the string of killings ending in Thomas’ death.

Thousands turned out for Timothy Thomas’s funeral, filling and then surrounding the New Prospect Baptist Church in Over-the-Rhine. Kweisi Mfume, national president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), flew in to speak at the funeral, calling Cincinnati “ground zero” for race relations in America.[5] As the hundreds of mourners, mostly African American, left the memorial service and wandered through the streets, some weeping, a squad car of Cincinnati police pulled up, pulled out shotguns, and shot at mourners, including one child with so-called “bean bags.” It was the ultimate insult and indignity.

The March for Justice

Throughout the rest of April and May groups met throughout the city in community centers and churches to discuss the killing of Thomas, the long string of killings of African American men, and as they did other issues came to the fore. Politicians’, business peoples’ and religious leaders’ attempts to foster reconciliation and a return to social peace as rapidly as possible led many to ask questions about economic and political power in the city. Things were not returning quickly enough to the status quo ante. Mayor Charlie Luken announced the creation of a privately funded organization, the Cincinnati Community Action Now (CAN) commission, “to help improve racial equity, opportunity and inclusion.”[6] Like all such “blue ribbon” panels, it was meant to present the appearance of concern and relieve the public conscience while leaving the essentials of the system intact. Rev. Damon Lynch III, pastor of the New Prospect Baptist Church and the man seen as the voice of the Over-the-Rhine community, accepted appointment to the commission, though he was later removed by Mayor Luken for his support of the boycott of the city.[7]

A few months earlier a new grass roots group had formed to challenge national, state and local economic policies—the Coalition for a Humane Economy (CHE). While not primarily concerned with race issue, when Thomas was killed, CHE activists immediately turned to organizing a response. The group involved community organizers such as Susan Knight and Steve Shoemacher, but also veteran black activists such as boxing coach Jackie Shropshire and his friend Henderson Kirkland, both members of the Black United Front. Some Stonewall activists as well as other LGBT activists also joined this new movement in solidarity with the black community. Out of this came the organizing committee for The March for Justice.

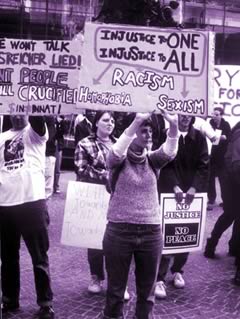

The March for Justice became the place that scores of activists—black and white, gay and straight—meeting each week in different churches around the city could work together to plan a protest as well as to develop a strategy to fight for justice. In planning meetings that sometimes attracted as many as 150 people, organizers projected a massive, legal and peaceful protest meant to challenge the city’s ruling elite, the business community, City Hall, and the police. As the 25-member steering committee planned for the march, the Cincinnati Police Department attempted to intimidate them, announcing that police with live ammunition would be prepared to deal with the protestors.

The March for Justice went ahead despite the threats and on June 2, 2001 attracted about 2,500—black and white, young and old, people from all walks of life—who marched in protest around and through the center of the city and passed in respectful silence the place where Thomas had been killed.[8] Finally the marchers gathered on Fountain Square, intermittently opening and closing their umbrellas in the spring rain, and shouted for Police Chief Tom Streicher, Jr. to resign.

Looking for a Lever: The Boycott

The March for Justice, where perhaps 80 percent of the marchers had been white, had impressed some leaders of the African American community who were looking to build the numbers and power to change Cincinnati. A group of black ministers led by longtime civil rights activist Rev. J.W. Jones asked for a meeting with March for Justice organizers to discuss strategies for pressuring the city’s establishment.[9] A coalition between the mostly white organizers of the March and the black ministers resulted in a new justice movement that began to look for some lever that would make it possible to force change. Soon activists from that coalition and other groups hit upon the idea of a boycott of Cincinnati as a way of pressuring the City’s economic and political decision makers.

Cincinnati as a whole was already being boycotted because of its record of discrimination against gay and lesbian groups. The LGBT community reacted in indignation and anger against Article XII, a city law which made it illegal to protect sexual orientation. In 1992 Cincinnati City Council passed a human rights ordinance which included sexual orientation, which in turn led conservatives on the Council to engineer a City Charter amendment to repeal protection for sexual orientation. Voters approved that amendment in 1993. The gay and lesbian community and its allies then organized a boycott of the city which led almost immediately to the cancellation of conventions and cost hotels and other tourist industries an estimated $40 million or more in contracts. [10]

In addition to the gay boycott of the city, the Black United Front had begun picketing and boycotting restaurants in September 2000 because 14 of 34 downtown restaurants had closed during the Coors Light Festival in July of that year to avoid serving black customers. The call for the picketing and boycott of the restaurants led the Justice Department to come to town to mediate the issue.[11] The following year when the Ujima Cinci-Bration and Coors Light Festival took place, as a result of the Front’s protest, there were no such problems; restaurants stayed open and served African American diners.[12]

Rev. J.W. Jones, the African American ministers, and the mostly white civil rights activists of the March created the Coalition for a Just Cincinnati (CJC) which initiated the new boycott campaign. Jones and the original CJC accepted the fact that African American and gay and lesbian citizens were both fighting injustice and discrimination, and accepted the idea of tacit alliance between the two groups. Others such as those in the Black United Front were uncomfortable both with the idea of black and white unity around the boycott and particularly with acknowledging any commonality with the gay and lesbian community. Stonewall Cincinnati was equally uncomfortable with entering into an alliance with the Front. Three leaders—two white and one black—who called for active solidarity with the African American community’s struggle were voted off the Stonewall board.[13]

These tensions—black/white and gay/straight—would lead to the fragmentation of the civil rights movement of 2001, though they did not completely paralyze it. The Cincinnati boycott of the early 2000s combined the tactics of the Front, boycotting the downtown restaurants and hotels, with the gay strategy of calling for convention and festival boycotts. The CJC took this one step further by calling for a boycott of the city by performers and entertainers – the “performers of conscience” campaign. Together these approaches would cost the city millions.

Cincinnati: Economic Apartheid

The boycott was not simply about police racism and violence. It was also about economics. Those involved in the March for Justice and the Black United Front argued that Cincinnati had not only a criminal justice problem but an economic and social justice problem. Over-the-Rhine, the neighborhood where Thomas had been killed, was a blighted community in every sense of the word. Back in 1950 it had been home to 30,000 people, 99 percent of them white, many descendants of the original German inhabitants who had come in the 19th century. During the 1960s African Americans from the West End had moved into the neighborhood together with whites migrating out of the Appalachian mining communities of Southeast Ohio, West Virginia, and Kentucky. Still the turnover in the community continued and by 2000 there were only 7,600 of whom 80 percent were black. Unemployment was high and median family income was only $8,000 per year. Many of the 5,200 habitable units in Over-the-Rhine could not meet the building code and were in dilapidated conditions. Among those buildings were another 500 standing vacant.[14]

While Over-the-Rhine was much poorer than most African American communities, still in many black neighborhoods in Cincinnati, such as Avondale for example, there were high levels of unemployment and too much poverty. Various federal, state and local development programs intended to help struggling communities failed to do so, with millions of dollars going to downtown development meant to attract suburban shoppers or to wealthier Cincinnati communities such as Hyde Park. These conditions led activists infuriated by the killing of Thomas and the others to link the criminal justice issues to an agenda of economic and social justice. The slogan became: “End the economic apartheid in Cincinnati.”

Several groups were eventually involved in the boycott of the city resulting from Thomas’s killling—Coalition for a Just Cincinnati, Cincinnati Black United Front, Coalition of Concerned Citizens for Justice, and the LGBT group Stonewall Cincinnati. Though they failed to unite, still the boycott had an impact, costing the city $10 million in its first year and turning away celebrities such as Bill Cosby, Barbara Ehrenreich, Whoopi Goldberg, Wynton Marsalis, Wyclef Jean, the O’Jays, the Temptations, and Smokey Robinson.[15] The boycott was so effective that in 2001 the Cincinnati Arts Association, the group which organized local concerts, sued boycott organizers for over $500,000 dollars.[16] The boycott organizers were ably defended by local attorney Lucian Bernard with national support from two attorneys with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF). The activists responded by suing the city, claiming that the government was infringing on their rights, and the matter was settled out of court. Some activists also received death threats for their involvement in support of gay rights.[17] The African American boycott continued for several years before finally petering out sometime in the mid-2000s.

The Legal Avenue: the Collaborative Agreement

Shortly before the killing of Timothy Thomas, the Black United Front and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) had brought a federal suit against the Cincinnati Police. The plaintiffs and the city reached an agreement—called the Cincinnati Collaborative Agreement—which, without blaming anyone, would attempt to change the police-community relations.[18] Thousands of Cincinnatians participated in focus groups and discussions which helped to inform the Collaborative Agreement.

Within a year, the U.S. Justice Department, which had been reviewing the Cincinnati Police Department, became involved in the Collaborative Agreement. Together the various parties agreed that the agreement would promote: “community-police oriented policing” to promote improved police-community relations; changes in the Police Department’s use of force policies; creation of an independent citizen’s complaint process. The final agreement was signed by President George W. Bush’s Attorney General John Ashcroft.

In response to the suit’s attempt to restrain them, the criticism they had received in the media, and the hostility of the African American community, police engaged in a several months slowdown that lead to a decline in arrests and a rise in violent crime.[19] Simultaneously, the establishment leadership resisted the Collaborative Agreement and the Justice Department’s intervention. While Mayor Charlie Luken initially attempted to thwart the process by refusing to pay attorneys, Police Chief Streicher resisted the monitoring of his force, and Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) union head Keith Fangman did his best to sabotage any plans for reform. The Police Department’s refusal to cooperate with the monitors finally led Judge Susan Dlott to suggest that she was ready to charge the obstructionists with contempt and jail them. The combined weight of Judge Dlott, the Justice Department, the ACLU and continuing pressure from the black community through the Black United Front and the NAACP which had also joined the suit kept the process going forward. The agreement served to inhibit the Cincinnati Police Department’s racist and trigger-happy practices and to end the string of killings of black men.

The Cincinnati National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

In the midst of this struggle over racial justice, on August 23, 2004, corporate Cincinnati opened the $110 million National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, celebrating past struggles against racism even as it ignored or attempted to stifle the contemporary fight for freedom. Jim Borgman, cartoonist at The Enquirer, captured the moment in his cartoon which depicted a wealthy white man shouting “Free at last!” as Cincinnati sloughed off its racist reputation by opening the magnificent National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. Some African Americans were not so thrilled. Activists from the Black United Front and the March for Justice responded to the opening of the center by setting up on that same date on Fountain Square their own “People’s National Underground Railroad Freedom Center,” a display of photos African American and white abolitionists, civil rights activists, and radicals and manifestoes of anti-racist movements. Some of those activists would for years afterwards boycott the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center.[20]

One interesting aside in all of this was consternation, bewilderment and amusement at learning that among others the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center celebrated Carl Lindner, owner of American Financial Group and the city’s richest man as a hero. He was listed as a local freedom fighter for supposedly for having integrated his Masonic Lodge. Many Cincinnatians remembered that Lindner was a former owner of Chiquita Brands International (the successor to the United Fruit Company) whose company had been accused in the Cincinnati Enquirer in May of 1998 of a string of abuses, including mistreating workers and violating their right to unionize, contaminating the environment, bribing foreign government officials, and permitting cocaine smuggling by the company’s ships. Chiquita denied the accusations and won a reported $14 million and other concessions for not suing the newspaper. [21] Chiquita might have won that legal battle, but United Fruit/Chiquita’s long history of skullduggery in Latin America could not be cleansed from the public memory. Carl Lindner’s name appeared on the list of heroes not because he had fought for freedom, but because he paid a lot of the bills, and everyone knew it.

As Damon Lynch III put it in 2003, the boycott organizers had never asked for a museum on the river, they had demanded jobs and housing in the neighborhood.[22]

Resolution?

What was the resolution of the police killings and the uprising against them? In 2003 the City of Cincinnati paid $4.5 million to 16 plaintiffs in what was the largest legal settlement in the city’s history. “The fact is, my son is never coming back,” said Angela Leisure, the mother of Thomas. “But my son isn’t the only son in Cincinnati.” The money could not relieve the pain of the families who grieved for their dead, but it could serve as a warning to the City and the Police Department that racist and violent behavior would be expensive. [23]

The Cincinnati Collaborative Agreement which resulted from the law suit brought by the Black United Front and the ACLU and later joined by the NAACP, and which led to Justice Department intervention, continued in effect for eight years (including a one year transitional period in 2008).[24] While almost everyone is in agreement that the Agreement led to improvement in police practices and in police/community relations, almost no changes were made in local laws and ordinances. Police Chief Tom Streicher, on whose watch the killings took place, was never fired. The city never created an independent police review board with subpoena power, a point considered by many to be the touchstone of healthy police/community relations.

Such progress as was made was not a result of the wisdom coming down from City Hall and the Police Department, nor from Proctor & Gamble, Krogers, Chiquita, Western Southern Life, and the other corporations headquartered in Cincinnati. Change came from the bottom up from the Black United Front and the Coalition for a Just Cincinnati and their boycott.[25] That is one of the most important lessons of the whole experience.

What Happened to the Movement of the Early 2000s?

When we look back, we can see that for two or three years, in response to the killing of Thomas, activists in Cincinnati had created a number of social and political organizations and built a large social movement. Hundreds of activists were involved and could sometimes move thousands. Why did that movement decline?

Damon Lynch, who had been appointed to and then canned by the CAN Commission in 2001 and later ran and lost a campaign for City Council in 2003, gave up leadership of the Black United Front.[26] Dwight Patton, who succeeded him as president in 2004, was a more ideological black nationalist and not a leader capable of working with white activists, rejected alliances with the gay and lesbian community, and was not capable of moving in the city’s elite and liberal circles as Lynch had. Subsequently the Black United Front gradually ceased to play the leadership role that it had in 2000 to 2002.

By 2002 Rev. J.W. Jones became too sick to continue to hold the Coalition for a Just Cincinnati together and then died, leaving the organization without a personality who could bridge the differences among the members. A power struggle over the leadership of the Coalition for a Just Cincinnati which had become the driving force of the boycott ensued. That split was followed by a second fracture eight months later over one CJC member’s participation in a demonstration with an anti-Semitic character. When the dust cleared, a group of the former CJC activists still committed to a black with white, gay with straight human rights perspective created Cincinnati Progressive Action (CPA), a mostly white activist group with a couple members of color.

The most important factor, however, was the desire of City Hall and local business interests to move forward with their political ambitions and business plans. The point after all, is to make money. As early as January 2002 Mayor Luken suggested that it just wasn’t fair that poor people were monopolizing some of the city’s best real estate. In discussing his State of the City address he had said that the announcement of his new Vine Street Project would “be a signal that Over-the-Rhine is a neighborhood for all, not just people at the lowest income level.”[27] So that’s what happened, City Hall and business began to make it clear that they wouldn’t let poor people stand in their way.

WHERE ARE WE NOW?

Where are we now, ten years later? We might begin by looking at the criminal justice issues and what has happened to Over-the-Rhine by turning to take a broader look at the city and the region.

Criminal Justice

While there seems to be a broad agreement that the Collaborative Agreement and Justice Department intervention in Cincinnati led to some improvement in police behavior, still we continue to have very disturbing incidents in our community that show the justice system’s persisting racism and violence, as well as the impunity of police officers. In October 2009, John Harmon, an African American man who works for a downtown marketing company, was heading home to Anderson Township just after midnight. He is a diabetic, and, when sugar levels fell low, he weaved in his lane. Hamilton County Sheriff’s Deputies saw him and, presuming he was a drunk driver, stopped him. A news report described Harmon’s experience:

What happened over the next two minutes and 20 seconds should never happen to anyone, Harmon said.

Deputies broke the window of Harmon’s SUV, shocked him seven times with a Taser, cut him out of his seatbelt and wrestled him to the ground, severely dislocating his elbow, and causing trauma to his shoulder and thumb.

The deputies’ actions prompted a state highway patrol trooper to pull one deputy away from Harmon because he was so concerned about how Harmon was being treated. That trooper alerted his bosses to the deputies’ actions.

Even after learning the incident was a medical emergency, deputies charged Harmon with resisting arrest and failing to comply with a police officer’s order.

“I thought for sure I was going to die,” Harmon said. “I remember praying to God, ‘Help me through this.’”[28]

Incredible as it seems, Hamilton County Prosecutor Joe Deters said that there would be no criminal charges filed against the Sheriff’s Deputies involved in the mistreatment of Harmon.[29]

The Harmon case is not the only example, and not the most horrifying. A few months before a police officer on duty in Over-the-Rhine accidentally drove his police cruiser over Joann Burton, a homeless woman sleeping under a blanket in Washington Park.[30] While no one thinks the officer’s action was intentional, still the killing of this woman certainly constitutes manslaughter (homicide without malice of forethought). Yet Prosecutor Deters decided that no criminal charge would be filed against the officer responsible.[31] Police officers and sheriff’s deputies in our area can continue to mistreat and even kill residents with impunity, despite the rebellion and reforms that took place in 2001.

At Burton’s funeral at New Prospect Baptist Church in Over-the-Rhine, a family member said that “Her time had come and God had called her,” but in his funeral sermon Pastor Damon Lynch III objected, saying that her death arose from and embodied the struggle between the wealthy and the powerful on the one hand and the poor and struggling on the other. “There is a land-grab going on,” said Rev. Lynch. “There are folks who don’t want the folks who are here to be here anymore.”[32] Washington Park, where Burton was killed, has been the center of an on-going thirty-year struggle between the low-income residents of Over-the-Rhine and the bankers, realtors, and developers who have sought to gentrify and transform the neighborhood into a community of young professionals and those of the “creative class.”

The Struggle for Over-the-Rhine

Since the late 1970s banks, realtors and developers have fought the Over-the-Rhine People’s Movement and neighborhood residents for control of some of the city’s most valuable land. City Hall and the wealthy wanted to displace the Appalachian and increasingly African American population from the area so close to downtown and use historic preservation and economic investment in the neighborhood to attract more upscale residents. Buddy Gray (he always spelled his name buddy gray), the leader of the movement, opposed historic preservation as a tool to increase property values and drive out the current occupants. He fought for more and better housing for the neighborhood’s existing residents rather than for economic development for the yuppies to come.

City Hall and business organizations waged a campaign against him. Businessman and politician Jim Tarbell—whose massive figure painted on a building in the neighborhood, dressed in top hat and tails today salutes the dwindling numbers of residents—was Gray’s most vehement opponent. Business groups put out posters and bumper stickers reading “No Way Buddy Gray,” in an attempt to make the city’s leading community organizer and poor peoples’ advocate a pariah. On November 15th, 1996, Gray was shot and killed by a friend, a mentally ill homeless man, one of many he had helped, who had somehow gotten hold of a high caliber pistol. Many believed that someone had put the man up to it and that Gray had been assassinated, though since the police believed they had caught the culprit no extensive further investigation was carried out.[33] As the Cincinnati Enquirer headline put it, “Over-the-Rhine now up for grabs.”[34] The grab was on.

The Over-the-Rhine People’s Movement gradually transformed itself during the 1980s and 1990s from a movement into a set of institutions: the Drop Inn Center for the homeless and ReSTOC to restore buildings for local residents. Meanwhile, however, with its buildings deteriorating and with few jobs in the central city for the residents, many residents began to leave the neighborhood. With the African American population declining the area became ripe for racial turnover and gentrification. Within a couple of years, businesspeople opened almost 20 bars and restaurants on Main Street that attracted one million mostly white visitors a year. During the 1990s the neighborhood’s low rents also brought in 10 internet start-ups. The 2001 ghetto rebellion and riots together with the bursting of the dot.com bubble ended that decade of gentrification.

By the 2000s, crime had increased as drug dealers worked out of corner grocery stores or stood on the streets peddling drugs to black and white customers from the city and the conservative white suburbs. Along with the drugs came increased violence including a rise in shootings and in homicides. By 2000 the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood population had fallen to 7,638—of whom 5,876 were African American.[35] Local media—TV, radio and the newspapers—constantly ran stories on the crime and violence in Over-the-Rhine, and City Hall and business interests seized on the new situation to make a final and successful push to take control of the community.

Operation Vortex and 3CDC

In 2003, City Hall and downtown business interests created a new not-for-profit organization—Cincinnati Center City Development Corporation or 3CDC—to develop Fountain Square, the Banks, and the southern reaches of Over-the-Rhine.[36] With the City Planning Department closed, 3CDC became the de facto agency overseeing economic development in the near downtown area. During this period local schools and parks were closed, a reflection of the declining population and fewer families, but also a deterrent to any future families moving in. Working with local investors, 3CDC then bought up local properties along Vine Street, the heart of the neighborhood—bought them, and then closed them. Where once thousands had paraded up and down Vine shopping at local stores and visiting with neighbors today there is a virtual ghost town—except for the block or two nearest downtown where several bars, restaurants and boutiques have opened. 3CDC, working with local investors, also oversaw the rehabilitation of local apartments, turning them from family dwellings into a virtual upscale youth hostel for students and young professionals.

Still the crime and violence and just the presence of poor black people proved an obstacle to further investment. So, in 2006 Cincinnati Police created “Operation Vortex,” an intensive policing program ostensibly intended to bust the drug dealers and dampen the violence in Over-the-Rhine, but also serving to drive not only criminals but other residents out of the neighborhood. In the summer of 2006 Vortex officers arrested over 1,000 people in 25 days.[37] Not surprisingly Vortex officers were more likely to stop African Americans, but, interestingly, they were more likely to find contraband on whites.[38] The ACLU filed suit against the City, charging it with violating the collaborative agreement by “improperly employing arbitrary arrest sweeps in the City.”[39]

Operation Vortex, together with 3CDC’s buy-‘em-and-board -‘em-up approach, represented a virtual scorched earth policy, turning Vine Street into an urban ghost town in the midst of the city. Despite continued resistance from the Drop Inn Center and other Over-the-Rhine organizations, the battle to save the neighborhood for its residents has been lost as so many of them have left in the last decade. The economic crisis of 2008, however, meant that, with little money available for credit and the economy stagnating in the Great Recession, most of the boarded up buildings have stayed that way with no gentry, no yuppies to occupy them. No one can claim to be the winner here.

THE BROADER PICTURE

We would make a mistake if we confined our thinking about these issues to Over-the-Rhine, for it is in its poverty and its suffering an extraordinary place. We should place that community and issues of criminal justice in the broader picture and take a hard look at the state of our city. What is the state of Cincinnati today and how does that determine the outlook for criminal justice and civil rights as well as economic and social justice?

Population and Unemployment

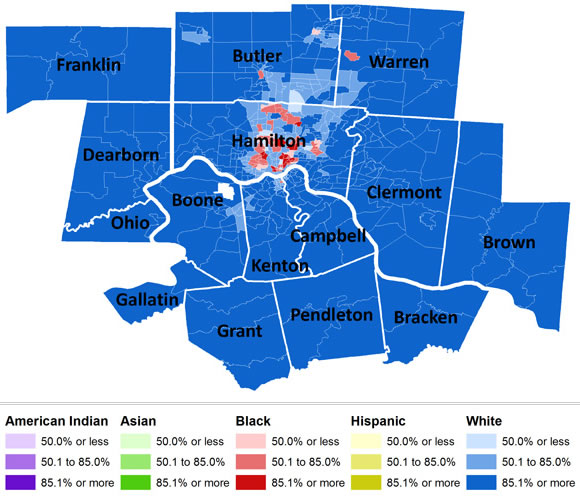

We should begin with the basics. Cincinnati’s population declined between 2000 and 2010 by 10 percent to settle at less than 300,000, while Hamilton County’s population also declined, though by only 5 percent.[40] Most recent statistics on racial demographics indicate that the city is about 53 percent white and 43 percent African American.[41] In 2011, Salon, the online magazine, found Cincinnati to be the eighth most segregated city in the United States.[42]

Why is the population declining? The city’s economy is not growing and workers can’t find jobs here; consequently many residents are leaving and few new ones are coming to live here. While this is principally an economic question, the city’s long history of discrimination against African Americans and gays and lesbians remains a factor, despite whatever gains have been achieved. The anti-immigrant policies of Sheriff Richard K. Jones of nearby Butler County help to discourage Latino immigration which has buoyed up so many other Midwestern and Southern cities. We have a city which, because of the deep class and racial divides and a long history of separation and exclusion, does not provide the synergies of diversity but rather still presents the stark black and white contrasts of apartheid.

The fundamental problem in Cincinnati as throughout Ohio and the entire United States is the problem of jobs. While the unemployment rate fell in March 2011 from 8.9 to 8.8 percent, it actually rose for African Americans from 15.3 to 15.5 percent as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Unemployment in the Cincinnati-Middleton Metropolitan Area is, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 10.8 percent, meaning that black unemployment here must be in the range of 17 percent. While African Americans in Cincinnati face such high unemployment rates, we cannot have economic and social justice.[43]

Organized workers in Cincinnati, whether in private industry or public employees, are under attack as at no time since the 1920s. The Republicans have succeeded in passing Senate Bill 5, virtually eliminating collective bargaining for public employees in the state—and a proposal to make Ohio a “right to work” state, that is to eliminate the union shop and destroy collective bargaining in the private sector as well, won’t be long in coming. Everywhere workers are facing pay cuts, demands that they pay more for health care, and are seeing their pensions reduced. The social safety net—Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security—are also under attack. Throughout the country both Republicans and Democrats are talking retrenchment, austerity, and belt-tightening. Cincinnatians, their belts already too tight, will be asked to tighten up a couple of notches more.

Ohio’s minimum wage was raised in January of this year to $7.40, the wage of some 270,000 workers in restaurants, retail work, housekeeping and other organizations according to Policy Matters Ohio. Everyone recognizes that the minimum wage is not a living wage. The minimum wage forms the floor for the entire wage structure of the state, and therefore other workers’ wages are also far too low. Many Cincinnati employers pay the minimum wage, and some don’t even pay that to immigrant workers who are routinely cheated out of their legal wages. The per capita income in Cincinnati is about $20,000 while household income is about $29,500. The city’s low incomes mean that for decades Cincinnati has been among the poorest cities in the country. In 2010 it was the third poorest city in the United States.

Since the economic crisis began, Cincinnatians have been losing their homes to foreclosure, or, in the case of renters, been put out as their landlords lost their buildings. While business elites and politicians talk about the economy rebounding in Hamilton County foreclosures continue and Sheriff’s sales actually increased. In 2010 there were 2,940 such sales, 300 more than the previous year. [44] Another source says that foreclosures have declined, but filings are still well above 1,000 per month.[45] Any way one looks at it, many Cincinnatians are facing the possibility of losing their homes or apartments and some of them will join the ranks of the homeless. Officially, the city has about 500 homeless people while another 500 are in transitional housing. The numbers are supposed to have fallen since last year, but even if they have fallen a few percentage points, the problem remains.[46]

Poverty

Over 25 percent of Cincinnati’s residents live below the poverty level, according to the citydata.com, while the rate for Ohio as a whole is 15.2 percent. Even worse, 12.1 percent of Cincinnatians have an income equal to only half the poverty level, as compared to 7.0 percent for the whole state.[47] Nor are things likely to change soon unless the citizens of Cincinnati and throughout Ohio take action.

Workers in Cincinnati, black and white, are under attack. The Federal government, which employs about nine thousand workers in the Cincinnati metropolitan area, has frozen wages for the next two years.[48] Republican government John Kasich and the Republican dominated legislature plan to cut state government and lay off state workers. This will affect thousands in the Cincinnati area. With the passage of Senate Bill 5, Ohio’s 360,000 state workers have lost their collective bargaining rights, making it more difficult for them to fight for higher wages and better benefits. The City of Cincinnati, which has 6,000 workers, has since the crisis began, laid off scores and plans to lay off hundreds of workers. The NAACP reports that 74 percent of those laid off in 2009 were African American.[49] So with the private sector failing to grow and government cutting back, unemployment will not improve very fast or very much and wages will remain stagnant or more likely fall. Poverty will continue in Cincinnati.

Where there is poverty, of course, there will be crime. CQ Press reported in 2009 that Cincinnati was the 19th most dangerous city in the United States.[50] While crime statistics are notoriously unreliable, still there is no doubt that Cincinnati has a high crime rate.[51] The inner city, where the population is mostly African American has the highest crime rate.[52] As the NAACP, Cincinnati Progressive Action and others in the community have argued, crime results from poverty, racism, lack of educational opportunities, and the lack of rewarding and well paying jobs.

Health and Education

More small children die in Cincinnati than in other parts of the state, and in our city’s poorer neighborhood, more children die than in other neighborhoods.[53] A study a few years ago found that infant mortality was 2.5 times greater for African Americans than for whites in Cincinnati, and the city’s rate higher than the county’s.[54] The City’s WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) program has helped to reduce infant mortality.[55] Now the city is planning to cut back its clinics and layoff health workers while school nurses may also be laid off, suggesting that children’s health will continue to suffer in Cincinnati.

The Cincinnati Public Schools claim to have made great gains in graduation rates, graduating 83 percent of entering ninth graders in 2010. At the same time the achievement gap between African American and white graduates has been closed, with whites scoring only 4.3% higher on graduation exams than African Americans.[56] Now schools are facing a $30 million dollar budget shortfall and administrators foresee the possibility of significant teacher layoffs. What will that mean for our children’s education?

Cincinnati’s New Immigrants

While for years racism and discrimination focused on African Americans, more recently Latino immigrants have also borne the brunt of such treatment. Cincinnati’s Latino community is now more than a decade old and has somewhere between 30,000 and 70,000 from Mexico, Guatemala and Peru, many of them undocumented workers who came to escape poverty and find work here to support their families back there. Most have found work in construction, meat packing plants, hotels and restaurants and many others jobs. Since immigrating, many have married either other immigrants or U.S. citizens, had children, who are, of course, U.S. citizens, and settled down into life in our city and suburban areas. Their kids go to the public schools and the parents belong to churches and social clubs. They have come to form an important new group in our city.

Ray Garcia, 4, wait with his mother, Maria Garcia, to hear news about his uncle who works at Koch Foods. Photo: Cameron Knight

While they make a significant economic contribution to our community, Latino immigrants are constantly faced with problems because of their legal status, but also because of their color, culture and language. In 2007, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers raided the Koch processing plant in the suburb of Fairfield and detained 160 undocumented immigrants. Most of the men were deported, while the desperate women and their bewildered children were allowed to remain for the time being with dates for deportation hearings sent a few months off.[57] That was under President Bush, of course. Under President Barack Obama, ICE has actually increased and expanded its deportation of undocumented immigrants by something like 30 percent, leading to the breakup of many Latino families.[58] In 2010, the Obama administration deported 387,790 immigrants, a record number; some were dragged off their jobs or out of their homes in Cincinnati.

Butler County’s Sheriff Jones has become notorious nationally for his aggressive stance against undocumented Latino immigrants. His deputies have been accused by critics of racial profiling and hostility to the Latino immigrant community. Jones policies have led some Latino immigrants to move out of the area and to other states.[59] While Jones has received the most attention, Sharonville Police have also made life difficult for Latino immigrants. Local Latino rights activists accuse them of racial profiling and harsh treatment of immigrants. While Cincinnati Police and Hamilton County Sheriff’s Deputies have not persecuted Latino immigrants, still any undocumented immigrant stopped for a routine traffic violation may find himself removed from the County Jail by ICE and quickly processed and deported—leaving spouse, children and friends behind. While concerns about discrimination in Cincinnati have focused on African Americans, we should remember that Latinos too have suffered with persistent racial profiling and discrimination from local police.

While we have talked here about Latino immigrants, we could also point out similar problems for the many African immigrants here, mostly West Africans from countries like Mauritania, and Arabs from Palestine/Israel or other regions in the Middle East. These immigrants too often experience problems at the hands of the authorities and also face discrimination and bigotry from other residents. The problems race and ethnicity have not gone away and in some ways they have become more complicated.

THE IMPORTANCE OF MOVEMENTS FOR CHANGE

What all of this makes clear is that what really counts in Cincinnati, that is improvements in the well being of all, and especially in the wellbeing of those who have the least, will only come with struggle. All of the gains of the past, the abolition of slavery, the organization of the labor unions, the winning of women’s rights, the civil rights movement, gay and lesbian liberation have only been won—insofar as they have been won—through developing a critical consciousness, through organization, and though struggles with the powers-that-be. We look then briefly at what may be the most important change that has taken place in Cincinnati in the last ten years, the change in political culture.

The Impact of the 2001 Events on Society and the Movements

One of the legacies of the protests of 2001 was a change in the political culture of Cincinnati. During the 1980s, social movements and political protests in Cincinnati were small and marginal. During the 2000s that changed, and social protest movements in Cincinnati came to number in the thousands, a reflection both of the change after the 2001 ghetto rebellion, and of the deepening of the country’s social and political crisis.

The new decade in America had been opened a little early by the Battle of Seattle of 1999, protests by labor unions and environmentalists in November of that year against the World Trade Organization’s ministerial conference held in that city. Thousands who had come to protest peacefully and to engage in direct action to stop the conference confronted mass repression by the city’s riot police but longshoremen, teamsters, and steel workers locked arms with environmentalists and refused to yield an inch. Inspired by the Battle of Seattle, Cincinnati activists had formed the Coalition for a Human Economy (CHE) and organized protests here against the Transatlantic Business Dialogue. Cincinnati police responded with repression, severely limiting assembly and speech, and arresting anyone—including passersby—dressed in black.[60] As mentioned above, CHE activists then joined the protests over Timothy Thomas’ killing. The Cincinnati’s ghetto rebellion of 2001, while caused by completely different issues, could be seen as part of the same rising trend in social protest.

This new spirit of rebellion was suddenly interrupted by the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, leading to a rapid rise in patriotism, militarism, government surveillance and repression, along with anti-Arab racism and anti-Muslim bigotry. The rightward shift, led by the media and the politicians, quickly cut off the rising wave of protest in places as different as Seattle and Cincinnati. Nevertheless, on October 7, 2002 thousands of Cincinnatians, joined by many hundreds from other cities in Ohio and around the Midwest, turned out for a protest in front of the Cincinnati Museum Center where George W. Bush announced his plan to make war on Iraq. Five thousand protestors, held back by mounted police officers, chanted and shouted their opposition to Bush’s war.[61] The spirit of protest returned once again to the city.

Another upshot of the events was Christopher Smitherman’s election to the Cincinnati City Council in 2003. Smitherman, a businessman and economic conservative, ran on a program of “fiscal responsibility, racial reconciliation, and improved community-police relations.” Modest as that sounds, what made Smitherman different than other local black councilmen and women was his desire to both learn and speak the truth. His outspoken demands for both economic accountability and racial fairness made him unpopular with some of his colleagues and especially with the powers-that-be. He was not reelected in 2005. Two years later, however, he won the election for president of the Cincinnati Chapter of the NAACP and began to turn it into a more vital organization. He spoke out and organized against racial discrimination in the justice system and opposed attempts to build a new and larger jail for a city with a declining population.

Two years later in November 2004, Cincinnati voters repealed Article 12, the charter amendment banning protection on the basis of sexual orientation. On March 15, 2006, the Cincinnati gay, lesbian and transgender community, led by the group Equality Cincinnati and backed by some local corporations, finally won its 13-year-long battle when City Council re-inserted sexual orientation into the City’s human rights ordinance. The vote was 8 to 1 with only Republican, Christopher Monzel, voting against it. Cincinnati now had a human rights ordinance with protections against discrimination[l1] in housing, employment and public accommodation, whether that discrimination was made on the basis of sexual orientation, religion, gender, race, color, age, disability, marital status and ethnic, national, or Appalachian regional origin. The LGBT community in Cincinnati felt both proud of the achievement and safer and more comfortable in the city.[62]

In January 2004, in response to President George W. Bush announced plans for immigration reform, 650 Latino immigrants meeting at the Catholic Hispanic Ministry’s Su Casa center in Carthage held the first meeting of what came to be the Coalition for the Rights and Dignity of Immigrants, the first truly immigrant-led immigrant rights movement in Cincinnati. For several years CODEDI led the immigrant rights movement in Cincinnati. On May Day 2006 about 1,000 Latino immigrants, organized by CODEDI and Su Casa, or simply coming on their own, took to the streets to demand immigration reform. The Cincinnati demonstration formed part of a tsunami of Latino immigrant protests throughout the United States, the largest in Los Angeles, Chicago and New York. In some cities they became a virtual general strike as hundreds of thousands of Latino workers left their jobs to join the marches and rallies. The Cincinnati march represented a sort of coming out party for Latino immigrants who had not taken to the streets before to manifest their presence and their desire for change.

Just one year later, in October 2007, thousands of grocery workers affiliated with the United Food and Commercial Workers Union (UFCW) held a rally in Fountain Square to demand a decent contract from the grocery corporations, such as Cincinnati-based Kroger company that employed them.[63] And just a couple of weeks ago, on March 15, 2011 some three thousand union members and their supporters rallied on Fountain Square to oppose cuts in education and to oppose Senate Bill 5, the bill to effectively end collective bargaining by public employees in Cincinnati.[64]

Among the most important achievements of Cincinnati’s political opposition in recent years was the defeat of two proposals—first one from the Republicans in 2006 and then one from the Democrats in 2008—to build a new and larger jail. The NAACP, Cincinnati Progressive Action, and the conservative COAST organization led two successful campaigns against a new jail, and Cincinnati voters defeated the proposition both times.[65]

We could mention other developments in the city that show a change in political culture. Take, for example, the creation of the Amos Project, “federation of congregations in Greater Cincinnati dedicated to promoting justice and improving the quality of life for all residents. AMOS develops the leadership skills of low-income and working families to be active in public life.” While that is a modest enough goal, for a collection of churches, synagogues and mosques made up of people of different races it is a very good one.[66]

Or to take another example, Cincinnati’s labor unions working with the Catholic Hispanic Ministry came together with others in March of 2005 to create the Cincinnati Interfaith Workers Center. The Center has since then undertaken the education and organization of low wage workers and immigrants. Among others it has worked to organize day laborers and to help immigrants fight employers who cheat them out of wages owned them.[67]

Finally, we could mention the Blue-Green Alliance, a partnership between the Sierra Club and the Steelworkers, later joined by other organizations, with the intention of creating jobs while protecting the environment.

One cannot attribute this entire history of grassroots mobilization, political opposition and social protest to the events of 2001, since many of them responded to national and international developments. Yet, I have little doubt that the 2001 rebellion played a role in changing the cities political culture. Since that date, social protests here no longer number in the dozens or hundreds but have several times numbered in the thousands. This is significant. Social protests help to create a new political consciousness, they inspire individuals, they build organizations and they create and push forward leaders. The rebellion and the many meetings and marches afterward, as well as the boycott, served to legitimate social protest, and we are better for it. Yet we must continue to educate and to organize, to resist and to rebel.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

The author, Dan La Botz, is a Cincinnati teacher, writer and activist who was directly involved in the protests in April 2001. He was present at the initial confrontation at the City Council committee meeting on April 8; he then joined other protesters at the First District Police Station that same evening; and later he participated in peaceful protest marches in the midst of the Over-the-Rhine rebellion. He was present at Timothy Thomas’ funeral where police fired on peaceful mourners. Afterwards he helped to organize the March for Justice of June 2 and subsequently he helped to found the Coalition for a Just Cincinnati (CJS) which was one of the boycott organizations. During the late 2000s he worked with Spanish speaking immigrants in CODEDI and responded to the ICE raid at the Koch plant. In 2008 he wrote the pamphlet Who Rules Cincinnati? (or at http://danlabotz.com). In 2010 he was the Socialist Party candidate for the U.S. Senate from Ohio. His book A Vision from the Heartland: Socialism for the 21st Century discusses the economic, social and political issues of Ohio, including questions of racial justice).

I could not have written this article without the help of my friends Linda Newman and Tom Dutton and my partner Sherry Baron. I alone am responsible for the opinions and views expressed in this article.

NOTES

[1] Jackie Shropshire, Henderson Kirland, and Suthith Wickrema participated in both organizations.

[2] Dan Klepal and Cindi Andrews, “Stories of 15 black men killed by police since 1995,” Cincinnati Enquirer

[3] An acquaintance of mine, a longtime civil rights and poverty activist, was pulled out of her car and beaten up. She understood and forgave those who attacked her. Others who were beaten were less charitable.

[4] My wife told me of an African American professional in her workplace explaining these realities of life in Cincinnati to her white coworkers at that time.

[5] Kevin Aldridge and Mark Curnutte, “NAACP leader calls for justice”

[6] Kevin, Aldridge, “Cincinnati CAN: ‘Willingness to shake things up’,” Cincinnati Enquirer at:http://www.enquirer.com/editions/2001/05/02/loc_cincinnati_can.html

[7] Kevin Aldridge, “CAN Leaders: Firing Lynch was right call,” Cincinnati Enquirer, Dec. 5, 2001

[8] Lew Moores, “Peaceful Marchers Cry for Justice,” Cincinnati Enquirer

[9] The meeting between the March for Justice Organizers and the African American ministers actually took place at my home in Clifton shortly after the march. Among those in attendance were Rev. J.W. Jones, Rev. Stephen Scott, Jackie Shropshire, Rev. Land, Rev. Doc Foster, and Rev. Donald Sherman. For Rev. Jones’ biography see: Rev. James W. Jones at Cincinnati Historical Society. While Rev. Jones accepted the idea of an implicit alliance with the gay community, some of the others had been opponents of gay rights.

[10] Lew Moores, “Cincinnati gay-rights appeal already costing conventions,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, [date?], 1993

[11] Allen Howard, “Black group to boycott restaurants, Closings during Coors Light Festival caused ire,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, Sept. 2, 2000; James Pilcher, “Restaurant pickets: ‘No truce’, Blacks protesters say they are out to make a point,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, Sept. 10, 2000

[12] Randy Tucker, “Restaurants to stay open for fests,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, June 27, 2001

[13] The three voted off the board were Mike McCleese, Heidi Burlins-Green, and Roy Ford. All three were active in the March for Justice. See: Doug Trapp, “Stonewall Decides,” CityBeat, Sept. 5, 2002; Clayton C. Knight, “New Fissures Appear in Stonewall,” CityBeat, July 4, 2002

[14] Jonathan Diskin and Thomas A. Dutton, “Cincinnati: A Year Later but No Wiser,”

[15] Issue Paper: Cincinnati Boycott

[16] The Cincinnati Arts Association suit asked for $87,000 in damages and $500,000 in punitive damages. It was thrown out on first amendment grounds but the CAA appealed; organizers countersued the CAA for governmental infringement of their civil rights, since the governing board was largely populated by local city and county officials. The CAA’s appeal and the counter-suit were later settled out of court, but the boycott activists did not agree to stop boycotting or to stop asking performers not to come to Cincinnati. The defendants in the case were Rev. James W. Jones, Amanda Mayes, Linda Newman, Rev. Stephen Scott, Rev. Donald Sherman, Michelle Taylor-Mitchell and “John or Jane Does 1 through 20.” Associated Press, “State judge throws out art agency’s suit against Cincinnati boycotters,” First Amendment Center. See also: Maria Rogers, “Right to Boycott,” CityBeat, Jully 25, 2002.

[17] I received two death threats in this period, one from a group called Wendepunkt. The same death threat was received by the owner of a gay bar and a Cincinnati judge. The individual responsible was convicted and jailed for his threat on the life of the judge.

[18] Collaborative Agreement

[19] Sheila McLaughlin and Jane Prendergast, “Police frustration brings slowdown” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 30, 2001.

[20] Thomas A. Dutton and Rev. Daman Lynch II, “The National Underground Corporate Center to Railroad Freedom,” Sept. 26, 2004

[21] Chiquita Branks International, Wikipedia

[22] Kevin Aldridge, “Boycott demands consolidated” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 8, 2002.

[23] Gregory Korte and Dan Horn, “City settles 16 police suits for $4.5 million,” The Cincinnati Enquirer

[24] All of the reports on the agreement can be found at: http://www.cincinnati-oh.gov/police/pages/-5111-/

[25] See for example, Gregory Korte, “Deal answers some of boycott demands” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 5, 2002

[26] Gregory Korte, “Lynch to run for City Council” The Cincinnati Enquirer, Aug. 20, 2003

[27] Gregory Korte, “Luken focuses on Vine Street” The Cincinnati Enquirer, Jan. 11, 2002

[28] Sharon Coolidge, “Lawsuit: Diabetic ‘pummeled,’ shocked by Hamilton County deputies” Cincinnati.com

[29] Sharon Coolidge, “Deters: No criminal case against deputies”

[30] Quan Truong, Jennifer Baker and Carrie Whitaker, “Woman dies after Cincinnati police car hits here in Washington Park” Cincinnati.com

[31] Trina Edwards, “Officer who ran over woman will not face criminal charges” Fox19.com

[32] Mark Curnutte, “Homeless woman killed in park is buried” Cincinnati.com

[33] Adam Weintraub, Buddy Gray shot dead; client held, Cincinnati Enquirer, Nov. 16, 1996, at; Dirk Johnson, “Gunfire Silences a Voice for the Poor” The New York Times, Nov. 30, 1996

[34] Cameron McWhirter, “Over-the-Rhine now up for grabs” Cincinnati Enquirer

[35] Cincinnati City government demographic statistics

[36] See 3CDC’s self-description

[37] “Operation Vortex Tragets Crime-Troubled Streets” WLTW.com

[38] Rand Report, “Police Community Relations in Cincinnati” 2007

[39] ACLU press release

[40] Jay Hanselman, “Census data show population decline in Cincinnati, Hamilton County” WVXU radio

[41] U.S. Census Quick Facts

[42] “The 10 most segregated urban areas in America” Salon

[43] See localtrends.com interactive map at: http://www.localetrends.com/cincinnati-trends.php Because the figures shown in these maps are based on government statistics which underestimate unemployment they are not entirely accurate. Unemployment is actually higher.

[44] “More local residents losing homes to foreclosures” Local 12, March 29, 2010.

[45] “Cincinnati foreclosures continue down trend in February” Business Courier, March 16, 2011

[46] “Cincinnati’s homeless population falls 12%” Business Courier, March 24, 2011

[47] Cincinnati Ohio Poverty Rate Data

[48] Dan La Botz, “Obama’s Federal Wage Freeze Will Become Model” Labor Notes; Malia Rulon, “Fed has deep impact on local workforce” Cincinnati.com

[49] NAACP Press Release, October 10, 2009.

[50] “Cincinnati” Wikipedia

[51] See “United States Cities by Crime Rate” in Wikipedia

[52] See the interactive crime map, neighborhoodscout.com, or another at: cincinnati.com

[53] Peggy O’Farrell, “Childhood mortality uneven across the city” Cincinnati.com

[54] John Besl, “Infant death haunts us all” The Community Research Collaborative Blog

[55] Noble Maseru, Cincinnati Health Commissioner, “Cincy Health Department’s WIC program recognized nationally for decreasing infant mortality” The Cincinnati Beacon, April 9, 2010

[56] Cincinnati Public Schools, Districtwide Graduation Rate

[57] Andrea Hopkins, “Immigration raids Koch Foods Ohio chicken plant” Reuters, August 28, 2007

[58] Julia Preston, “Firm Stance on Illegal Immigrants Remains Policy” New York Times, August 3, 2009

[59] Jennifer Ludden, “Latinos Rattled by Ohio Sheriff’s Mission” NPR, June 19, 2006

[60] Valerie Miller, “TABD Conference, Protests End,” WCPO TV 9 (Scripps Howard) ; “Trade Forum Sparks Protest in Cincinnati”

[61] Dan La Botz, “Cincinnati: Protest in the Heartland”

[62] Eric Resnick, “Cincinnati Passes LGBT human rights ordinance” Gay Peoples Chronicle

[63] UFCW, “Cincinnati Workers and Supporters Rally by Thousands”

[64] Jay Warren, “Union members rally at Fountain Square”, WCPO, at

[65] Dan La Botz, “Troublemaker’s Journal, No Justice, No Jail” Wednesday, May 23,2007.

[65] The Amos Project

[65] Cincinnati Interfaith Workers Center

Comments

One response to “Cincinnati: A Decade since the Rebellion of 2001 – What Have We Learned, Where Are We Now?”

The statistics of the number of unarmed, innocent people killed by police should not be mixed with the statistics of people armed with guns who were in a confrontation with police.

Institutional racism is real. It’s a problem that’s not going away until everyone, especially the privileged white members of our society, look it straight on and address it. And it’s not a problem that is going away any time soon. But inflating the statistics with numbers of confrontations of police with armed aggressors obfuscates the facts, and inflames an already highly sensitive dialogue.