Posted April 7, 2009

In our times, it is rare that art and politics come together well. Too often what we classify as “art” is either aesthetic rich and content poor, or some sort of insider joke, something made valuable mostly by its inability to be understood by anyone but the members of selective, small cultural and intellectual circles.

Likewise, in our era political statements are too often crude and artless, lacking not only aesthetic sensibility but also immediacy and emotional power.

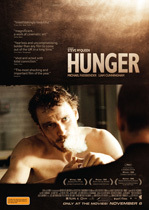

“Hunger,” by filmmaker Steve McQueen and playwright Enda Walsh, is art at its finest, a moment where form and content are woven together. The film is an account of the prison struggles in the late 1970’s-early 1980’s waged by imprisoned IRA members to demand status as political prisoners and enact prison reform. At its center is the figure of IRA leader and martyr Bobby Sands, who died in 1981 after 66 days on hunger strike.

“Hunger,” by filmmaker Steve McQueen and playwright Enda Walsh, is art at its finest, a moment where form and content are woven together. The film is an account of the prison struggles in the late 1970’s-early 1980’s waged by imprisoned IRA members to demand status as political prisoners and enact prison reform. At its center is the figure of IRA leader and martyr Bobby Sands, who died in 1981 after 66 days on hunger strike.

Hunger, while being unapologetically political, avoids the common failings of much political art. It neither waters down the realities of the political struggle nor lapses into preaching. It is both personal and political. The struggles of the prisoners, who at different points refused prison clothes for blankets and refused to bathe or have their hair cut (the so-called “dirty protest”) are anything but glorified. The filmmaking is brutal in its accounts of the boredom, the filth and the violence of the prison protests. What does emerge is a powerful account of the personal sacrifice IRA members underwent to achieve their aims, the unshakable discipline of the IRA, and the raging inhumanity of the official response by authorities.

IRA violence is not glossed over. In one memorable scene, a prison official, visiting his elderly and senile mother, is shot point-blank by an IRA assassin, covering the mother with blood. In all of these moments the filmmaking ultimately honest, particularly in its portrayal of violence; instead of the victor, the camera shot is on the dead and those who have been physically and emotionally brutalized.

Neither is Sands’ death glorified. The easy answer of a martyr’s story is missed, instead the moments of Sands slipping into death are both brutal and intensely personal. The final shots are not of Irish flags, or marches, or even of other human beings. Instead they are memories from Sand’s youth, alone in the forest, stressing if anything the intensely individual experience of death, even while Sand’s mother watches.

This film has won a number of awards, including the prestigious Camera d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. It is a pity that Hunger is not screened more widely in the United States, the nation with the world’s largest and greatest per-capita prison population, where we so recently have created our own Caribbean Gulag. Perhaps the discipline and intensity it portrays would be out of place in a nation lulled to sleep on the intellectual junk-food diet of reality TV. Perhaps for this reason, if no other, Hunger should be seen by Americans.

[Christian Roselund, a friend of Solidarity’s New Orleans branch, wrote this review]

Comments

2 responses to “Hunger – Art and Politics come together [movie review]”

Going to have to see this one.

Patois, the 6th Annual New Orleans Human Rights Film Festival is currently underway, running through April 5. It includes dozens of inspiring shorts and full length films. Check it out!- Robert C.

http://patoisfilmfest.org/