Alan Wald

Posted March 12, 2024

Writers and Missionaries:

Essays on the Radical Imagination

By Adam Shatz

New York: Verso, 2023, 357 pages,

$29 hardback.The Rebel’s Clinic:

The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon

By Adam Shatz

New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

2024, 451 pages, $32.00 hardback.

ARE YOU THE kind of socialist activist looking for easy answers to questions about revolutionary violence, or who hungers for uplifting political biographies of icons of radical commitment?

If so, Adam Shatz is a writer you should probably shun. His two recent books are testaments to a fierce curiosity that evokes the more perplexing and incongruous aspects of intellectuals and their social responsibility, often with a unique emphasis on anticolonialism.(1)

Zealots, beware! It is his unblinking assessments of authors and activists, and the courage to zig where most choose to zag, that have become Shatz’s signature method in a quest to reveal the intricacies of theory and practice of avant-garde cultural figures in Europe and the Middle East.

Yet Shatz’s unsettling appraisals may be just what we require at this fraught political moment. They speak to several issues turbo-charged by the 7 October 2023 bloodshed in Israel, and the industrial-scale genocidal onslaught that has followed. His well-versed approach may help clarify long festering debates about what constitutes meaningful socialist commitment to Palestinian liberation and the indispensable eradication of Zionist settler-colonialism.(2)

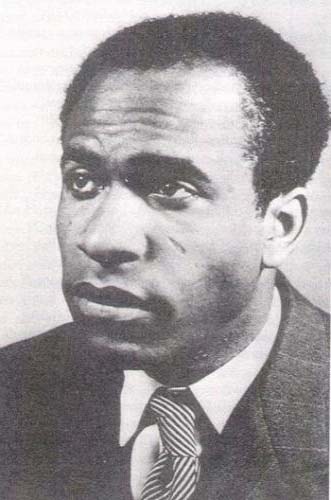

Adam Shatz is a middle-aged Jewish American radical journalist who came to political consciousness under the impact of the First Intifada (1987-93), and then educated himself by reading Jewish anarchist Noam Chomsky, Trotsky biographer Isaac Deutscher, and Palestinian radical scholar Edward Said.

Best-known today as the U.S. editor of the London Review of Books, he is also a contributor to prominent left-leaning intellectual publications such as the Nation, New Yorker, and New York Review of Books. Nevertheless, Shatz has no hesitancy about sharing information and offering interpretations that might upend practically any partisan narrative.

Writers and Missionaries, his scintillating collection of essays from Verso publishers, might be read as an appetite-whetter that explores a range of complex motivations and enigmatic affinities of a selection of writers, many of them leftwing. Then comes the main course, which takes his enterprise to a whole new level: The Rebel’s Clinic, a gobsmacking life story of Afro-Caribbean Marxist psychiatrist Frantz Fanon (1925-1961).

Fanon and Algeria in Context

It is when he turns to Fanon that Shatz situates the passionate calling of the biography’s beguiling protagonist in the context of the punishing paradoxes of the Algerian anticolonial resistance to French domination, and especially the staggering amount of violence during the decade of war (1954-1962).

A defiance of French colonial brutality was obligatory, and colonization is by and large to blame for the perhaps 1,500,000 Algerians who were killed along with 26,000 French soldiers and 6000 Europeans. Yet too many of the pitiless deaths of civilians were due to internecine factional struggles among the Algerians.

Some sources estimate that 12,000 militants were killed in an internal purge, and another 70,000 in clashes between parties. This practice of liquidating rival nationalists was even carried over into the Algerian population in France where it took another 5000 lives in the so-called “Café Wars” — bomb attacks and assassinations in coffee shops.(3)

Unquestionably, for socialist-internationalists Algerian independence was a legitimate cause if there ever was one, with French Trotskyists and anarchists the honorable initiators of European support.(4) In spite of that legitimacy, the victory was followed over decades by hundreds of thousands of more deaths of Arabs and Berbers due to the domestic tyranny of the post-colonial elite that had its roots in earlier repressive behavior.

Algeria today is a human rights disaster marked by restrictions on free speech and religion, mass arrests and torture, and a failure to implement laws to prevent feminicide.(5) Unless one is an absolute determinist or fatalist, such a past record should cause today’s solidarity activists to ask conscientious questions.

The issue is not the validity of armed resistance in itself, but the policies, programs, ethics and culture of any revolutionary or nationalist organizations presently in contention to lead an anticolonial social transformation.

Certainly, the need to take action against colonial oppression can be exigent, and attention-grabbing exploits of armed resistance often demonstrate courage as well as conviction. All the same, daring feats recurrently overshadow attention to political program and a group’s history. A military success does not necessarily assure future liberation, and building a better society remains the real goal.

Can solidarity activism offer a blank check to any organization that comes to the fore in the name of “resistance”? All revolutionary acts advancing liberation should be supported, but what qualifies? Is every kind of rebellion productive? Should one organization alone be allocated a monopoly over the struggle?

From the outcome in Algeria and numerous other countries during the Post-colonial Age, we know that national liberation is demanded but that specific political movements can go utterly wrong.

Politically Effective Resistance

Issues arising from the Algerian political aspect of Fanon’s career explain why Shatz’s volume has received considerable attention in the press following the events of October 7. That was the day when the Islamist Palestinian group Hamas launched its own audacious act of anticolonial rebellion against a long-violent Israeli state by breaching the imprisoning sixteen-year blockade of Gaza.

Joined by other factions and individuals, the Hamas-led raid spun into acts of gruesome counter-violence against everyone encountered, including defenseless and helpless victims. Scores of civilians, not just Israeli and other Jews (many attending a Peace music festival), but foreign workers and Arabs (especially Bedouin) were slaughtered or taken hostage, and women likely raped and tortured.(6) Israeli soldiers became prisoners of war.

Many aspects of the bloody clash are still in dispute; Israeli state propaganda should not be automatically believed, especially since there have been lies about beheadings of babies and cover-ups of Israelis killed by crossfire of the IDF (Israeli Defense Force).

Nonetheless, October 7 was immediately exploited as a pretext for a dramatic intensification of Israel’s ongoing genocidal assault on the far greater number of defenseless and helpless Palestinians in Gaza.(7)

The whole lacerating sequence soon catapulted the problem of what constitutes politically effective resistance to colonial oppression to the foreground of debate and discussion. How to achieve liberation in an asymmetrical situation of extreme inequality is especially problematic, more than ever when a stateless population faces a powerful state and the weaker side can’t fight with normal military means.

Among the anticolonial Left there was no disagreement about reaffirming support to the just cause of Palestinian liberation. Condemnation was focused on the Israeli carpet-bombing and invasion of Gaza that swiftly exposed the monstrous inhumanity of present-day political Zionism. Mass action for a permanent cease-fire became the immediate project, along with demanding the end of U.S aid to the Israeli state.

In distinction to liberal Zionists who may have been distressed by “excesses” of the Netanyahu government but who refused to address the root cause, socialist-internationalists persisted in making their long-standing argument for the thorough transformation of the ethno-religious Israeli state.

This solution must occur through the abolition of apartheid and colonial privilege, replacing these with a new multinational state or federation that secures the democratic rights and security of all people from the river to the sea. But how would that objective be achieved and who would carry it out?

Are the ideology and strategy of Hamas to be publicly embraced, passed over in silence, or cagily massaged by characterizing October 7 as a “military action” with “tactical” matters left to be discussed later?

What to make of the past history of Hamas rule in Gaza with no free political discussion, no freedom of the press or assembly, repression of gender equality, and antisemitic propaganda? Is there really a case for its liberating potential?

Along with mobilizing for action against Israeli state genocide, how does one also address these matters to build the critical-minded socialist movement needed here? Shouldn’t our stance be one that that maintains the right of anticolonial resistance but also listens to and learns from veterans of anticolonial struggle, and an assortment of Palestinian activists, to advance beyond errors of the past?

Of course, Shatz’s books were written before October 7 and hardly provide a blueprint for present-day policy.(8) He is emphatically opposed to racism, colonialism and “actually existing Zionism,” and not unsympathetic to the right of armed resistance. Nevertheless, his research and writing (including many previously uncollected pieces) raise issues about troubling dimensions of heartfelt political commitment as well as the long-term consequences of revolutionary action.

Shatz accomplishes this not by political directives (I don’t know many of his specific views), but by excavating and probing the concrete circumstances of actors and social movements, often raising questions that haven’t been asked by others.

That’s why his work can be poison to those who are curiously incurious about the nuanced realities and shape-shifting nature of class and anti-imperialist struggles as they evolve over time, not to mention the frequently messy lives of even those who are heroically pledged to a liberatory future.

Shatz launched his career with certain principles that he has not abandoned; but through the years he has become increasingly a listener, especially to those with first-hand involvements and standpoints outside the United States and often the West.

Beyond this, Shatz is also a writer who has mastery over a dizzying array of topics such as modern Jazz, Marxist and postmodern theory, anthropology, creative literature, film, cooking, and much more. Since all Shatz’s work entreats us to think harder, I find it beneficial to start with a consideration of his essay collection before moving on to the more ambitious Fanon biography and the topic of anticolonial politics.

Realistically Imperfect Individuals

While Shatz edited a 2004 volume, Prophets Outcast: A Century of Dissident Jewish Writing about Zionism and Israel, demonstrating the disastrous consequences of Israeli state policy, Writers and Missionaries is the first selection of his own work.

The seventeen chapters are mostly from the London Review of Books starting in 2003 and are divided into four main parts that address complicated intellectuals from the Arab world, as well as African American writers in Paris, French cultural superstars, and various problems of commitment. The collection is capped off with an amusing but somewhat out-of-place memoir of Shatz’s culinary obsessions, “Kitchen Confidential.”

If, like me, you like your biographical portraits to be of realistically imperfect individuals whose fascinating flaws are effusively fleshed out, you will be speedily seduced by Shatz’s direct and engaging style: “But speaking truth to power, and aligning oneself with the oppressed, is less straightforward than it seems.” (10)

For starters, Shatz never clubs the reader over the head with a prowess at erudite allusions or an excess of cerebral witticisms. His portraits proceed with a galvanizing panache, far more than just journalistic competence: “the weapons of truth-telling could not protect the dreamer from his illusions, and defend him against his assassins, who had real weapons…” (11)

Shatz’s studies also exhibit a capacity to offer clear and compelling synopses of an extraordinary amount of historical background and often recondite intellectual material. Some of his subjects, regrettably, are poorly known in the West, such as the Lebanese-born scholar Fouad Ajami (1945-2014), the Algerian journalist Kamal Daoud (b. 1970), and the assassinated Jewish-Palestinian actor/director Juliano Mer-Khamis (1958-2011).

These biographical investigations are largely derived from personal interviews in Middle Eastern countries as well as close readings of the written work. Far from aiming to present a catalogue of weaknesses and hypocrisy, Shatz sets out “to explore the difficult and sometimes perilous practice of the engaged intellectual: the wrenching demands that the world imposes on the mind as it seeks to liberate itself from various forms of captivity.” (7)

Other subjects are world-famous if not always widely understood, such as the structuralist anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2008), deconstructionist philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), semiotic literary theorist Roland Barthes (1915-1980), and novelist and film-maker Alain Robbe-Grillet (1922-2008).

I can’t claim expertise in all these figures but can attest to the lucidity with which Shatz unravels their achievements and activities. Lévi-Strauss, he demonstrates, cannot be understood without acknowledging his deep distaste for his status as a public figure. Robbe-Grillet, whose career was marked by a great renown and very few readers, was captive to a “literary imagination” serving as “a playpen for his criminal passions and victimless crimes.” (233)

On the other hand, the Black radical expatriate writers portrayed in the section called “Equal in Paris” are my specialty, so I can verify Shatz’s eerie accuracy apropos the quality of their work and the complications of their political thought.

The ordeal of Richard Wright (1908-1960) and his fraught relations with other African American writers has rarely been depicted with such subtlety and sympathy, and the “radical humanism” (166) of pro-Algerian William Gardner Smith (1927-74) is reclaimed with an intimate understanding of the challenges of exile.

Most intriguing, perhaps, is what Shatz provides about three French radicals who boil over with incongruities: documentary producer Claude Lanzman (1925-2018), New Wave filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville (1917-73), and the existentialist philosopher and activist Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980).

The last comes in for an engrossing treatment in a two-fold narrative of Sartre’s unhappy estrangement from the Egyptian intellectual Left, which suffered from its own “conflicted attachment to [Egyptian President Gamal Abdel] Nasser.” (302)

Shatz’s chronicle of Sartre’s failed balancing act between what seemed like hardcore values and the emotional force of a current friendship is a startling and edgy marvel. I am reminded, once again, that even though we radicals believe in the objectivity of our choice of ideology, its expression can also be tweaked by psychological and personal needs.

Not every subject of Writers and Missionaries could be called radical in a political sense, but Shatz sees all as expressing a “radical imagination” through “a style of thinking that seeks to penetrate the root of a problem and expose ‘what is fundamental.’” (9) This formulation, along with his guiding distinction between “Missionaries” and “Writers,” which came to him in a conversation with Trinidadian-born novelist V. S. Naipaul, remains a bit nebulous to me.

Perhaps this phrase and those terms are less clarifying for the general reader than they are functional for Shatz himself, as mechanisms to herd his heterogenous selection of writings under a common rubric. The volume’s all-male cast of characters is a more notable deficiency in an otherwise extraordinary survey.

Fanon: Fusion of Life and Work

Shatz’s genius at recovering the multifariousness of authentic people from the gray mists of ignorance, prejudice, or hagiography, is on full display in The Rebel’s Clinic. With Fanon we confront an all-embracing radical political commitment that means the fusion of one’s life and work in a common goal.

First, Fanon’s writing and psychiatric practice are put in the context of his biography, and then his biography is put in the context of his developing engagement in revolutionary struggle. This sometimes contradictory progression is explained as a kind of palimpsest of stages, a long and fitful evolution wherein each new development doesn’t erase but challenges and stretches what came before.(9) Such a narrative reads like a mystery that only gets more intriguing as it unfolds.

The skeleton of biographical facts about Fanon is well-known from numerous previous book-length studies, one of which I reviewed for the Marxist journal International Socialist Review fifty years ago.(10) Born to a middle-class Afro-Alsation family on the island of Martinique, then a French colony in the Eastern Caribbean Sea, Frantz Omar Fanon attended school there until he volunteered to fight fascism in General de Gaulle’s Free French Forces in 1944. He served in North Africa and then in Europe, where he was wounded and received the Croix de Guerre.

During a sojourn back in Martinique he befriended the poet and Communist activist Aimé Césaire (1913-2008), from whom he absorbed an interest in Negritude (the movement accentuating pride in one’s African heritage). He then attended medical school in Lyon, where he was profoundly affected by the lectures of phenomenological philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961).

In these years his consciousness of French racism deepened as he came to see it and colonialism as noxious betrayals of the Enlightenment ideals that had inspired his military service.

After publishing Black Skin, White Masks in 1952, he married radical journalist Marie-Josèphe “Josie” Dublé (1930-1989), and relocated to Algeria as head of the Blida-Joinville Hospital. Drawn quickly into support of the Algerian Revolution, he found himself treating victims of French torture and sometimes the torturers, to whom he responded with inordinate compassion.

After two years Fanon was forced to resign his position when his political affiliation with the FLN (National Liberation Front, formed in 1954 in a split from the MTLD, Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Liberties) became known. He then relocated to Tunisia where he held an editorial post on the FLN newspaper El Moudjahid.

Having now become a representative and public spokesman for the FLN, he attended political and literary congresses, even after he was seriously injured by a land mine along the Algerian-Moroccan frontier in 1959. This was the year he published A Dying Colonialism, a virtuoso analysis of the Algerian war for independence.

In 1960 he was appointed Ambassador of the Algerian Provisional Government to Ghana but was diagnosed with leukemia and traveled to the Soviet Union for therapy. In 1961 he went to Washington DC for treatment at the National Institutes of Health, dying on the eve of the publication of his masterpiece, The Wretched of the Earth.

The Rebel’s Clinic, however, is much more than just a portrait of Fanon. In the process of recounting Fanon’s evolution, Shatz situates many intellectual figures who interacted with him and influenced his writing.

In addition to several already discussed, some of the most noteworthy include the abovementioned Sartre; the Catalan psychiatrist and anti-Stalinist Spanish Civil War veteran Francois Tosquelles (1912-94); the French Freudian psychoanalyst Jean Oury (1924-2014); the Senegalese poet and first president Léopold Senghor (1906-2001); the Algerian-born French author Albert Camus (1913-1960); the French feminist Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986); the French journalist and political activist Frances Jeanson (1922-2009); the French pro-FLN doctor Pierre Chaulet (1930-2012); the French psychoanalyst Octave Mannoni (1899-1989); the French psychiatrist Jacques Lacan (1901-1981); the French publisher Francois Maspero (1932-2015); and the French-Tunisian essayist Albert Memmi (1920-2020).

Although his admirable qualities of discipline and dedication were paramount, Fanon himself was not a man without vanity, and he had several disturbing traits. One was a dangerous attraction to strong men in the revolutionary movement, the type who disparage emotions and sentimentality, and too often conflate a personal drive for power with the good of the struggle.

Another was a troubling homophobia, reflected in Fanon’s skepticism that homosexuality could have existed in his native Martinique. (206) And then there was a male chauvinism, exhibited in the possibly abusive treatment of his wife, Josie.(11) She had become a capable and committed revolutionary editor, to whom Fanon dictated much of his work.

Fanon has been panned by feminists for his portrayals of colonized women, and Shatz notes that he slighted de Beauvoir, who seems to have inspired his ideas with The Second Sex (1949) but whose influence was never openly acknowledged. (89, 97)

As a member of a disciplined cadre group, the FLN, Fanon remained silent about the strangulation murder of his mentor, Abane Ramdane (“the architect of the revolution”), by jealous rivals who later said he died in battle.

Fanon was then duped by the Angolan CIA agent Holden Roberto and played a questionable part in the downfall of Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba. Nonetheless he held up rather well overall, in spite of having to endure the mental strains of being a marked man under threat of assassination.

Specialists in Fanon, and well-informed readers of books and articles about him, may not find copious new factual material in The Rebel’s Clinic. Moreover, certain matters that radicals hold to be of political importance are not mentioned, such as the claim of Marxist scholar Peter Hudis that during a Paris residence prior to Lyon, Fanon “obtained and studied the works of Leon Trotsky as well as the proceedings of the Fourth International.”(12)

Violence, Perils and Promise

The virtue of Shatz’s book is that its thought-provoking arguments are reasoned out with a savvy cogency, craft, and assurance that draw on decades of distilled research. A good deal of Fanon’s formidable impact on contemporary thought is reviewed by Shatz with admirable lucidity and concision.

Fanon’s influence on psychiatry is immense among those who understand personal pathologies as political symptoms and advocate varieties of social therapy that consist of group settings. His understanding of Black alienation as a form of amputation or imprisonment under colonialism has long been celebrated, as has been his argument that colonized people internalize feelings of inferiority and aspire to emulate their oppressors.

More recently Fanon has become established as a major interlocutor in post-colonial discourse analysis (PCDA), especially regarding the presentation of historical events from the standpoint of the colonized and delving into matters such as the connections between language and social structures of power. Such developments lead Shatz to proclaim that, in the new millennium, Fanon would be “reborn as a French theorist.” (370)

When it comes to the question of Fanon and anticolonial violence, the focus of this review essay, it is imperative to recognize that Shatz is hardly the first biographer and commentator to observe the existence of ambivalences and contradictions throughout Fanon’s work.

The competition to be the latest ”Fanon Whisperer” has been steep, and many books and articles have deplored the tendency of partisans to latch on to certain sensational passages about violence in the first chapter of The Wretched of the Earth. These may be used to rationalize acts of brutality of which they approve, or which they don’t wish to acknowledge for what they are, while most of the rest of this book, as well as Fanon’s writings as a whole, are ignored.

To this day, one sees decontextualized Fanonian references to violence as a “cleansing force” that frees the colonial rebel “from his inferiority complex and his despair and inaction; it makes him fearless and restores his self-respect.” Another common quotation from Fanon is that “it is precisely at the moment he [the native] realizes his humanity [through a violent action] that he begins to sharpen the weapons with which he will secure his victory.”(13)

There are certainly more than a few phrases like these that stand out like daggers in The Wretched of the Earth. Yet to grab onto such sentences, as zealously as a religious person recites favorite passages in a holy book, is simply to co-opt Fanon as symbolic capital for a politics that he may have abhorred.

Much in Fanon remains open to multiple interpretations, but there is no doubt that the totality of his dispersed views on anticolonial violence adds up to the paradoxical assessment that the violence of the colonially oppressed is fraught with as much peril as promise.

Many nuanced views by Fanon are indicated by specific statements that Shatz brings to light. Moreover, the horrific trajectory of the revolution in the years after the 1962 victory completely contradicted Fanon’s prediction of a “new Humanism” in Algeria.

In brief, what he meant by “New Humanism” was a restructuring of relationships distinct from European liberal imperialism, one that emphasized decentralization, new subjectivities and cultures (not fundamentalist and traditional ones), and also a rejection of the one-party states already appearing in revolutionary societies in Africa.

Fanon’s failure to recognize that his FLN was producing precisely what he opposed suggests that he was subject to romanticization and naiveté, too readily succumbing to a pressure to conform — traits we dare not repeat today.

Here are a few examples of the book’s elucidations. According to Shatz, the word “cleansing” in the above quotation is a mistranslation of “disintoxicating” (155), which is not quite the same in meaning.

Yes, to stand up physically to one’s oppressor can be liberating and empowering, an action famously dramatized in Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life (1845) where the future abolitionist strikes down the slave-breaker Edward Covey.

However, Shatz believes that Fanon’s emphasis on this stage in a violent revolt was not intended to advocate a long-lasting cure-all. Rather, it described a perilous but necessary step in the journey toward decolonization and reclaiming identity. That’s because there is plenty of evidence in Fanon’s writing to show that violent behavior is damaging and easily turned in the wrong direction.

Moreover, although Fanon understood that violence was inevitable in the colonial situation, he also argued in The Wretched of the Earth that violence should not be taken as a political strategy and that all members of the French settler population should not be seen as existential enemies:

“The people who, in the early days of the struggle, had adopted the primitive Manichaeism of the colonizer — Black versus White, Arab versus Infidel — realize en route that some Blacks can be whiter than the whites, and that the prospect of a national flag or independence does not automatically result in certain segments of the population giving up their privileges and interests…The people discover that the iniquitous phenomenon of exploitation can assume a Black or Arab face.” (156)

Shatz points out that Fanon publicly lied about the FLN’s responsibility for the June 1957 massacre of 300 Muslim inhabitants of the Melouza village, a community allegedly sympathetic to the rival rebel group MNA (Algerian National Movement, successor to the MTLD). But Fanon also made a general statement against atrocities in A Dying Colonialism:

“(B)ecause we want a democratic and renovated Algeria, because we believe one cannot arise and liberate oneself in one area and sink in another, we condemn, with pain in our hearts, those brothers who have flung themselves into revolutionary action with the almost physiological brutality that centuries of oppression nourish and give rise to.” (195)

Beyond this, it is clear that Fanon’s emphasis on the necessity of violence was primarily connected with his view that de-colonization must be seized, not given, and there are instances where Fanon advised specifically against the violence of hate and revenge, arguing that any violence must be disciplined and targeted.

On the other hand, none of this adds up to a clear policy for practice today, and certainly not one as well-defined as the Freedom Charter of the ANC (African National Congress) about the centrality of non-racialism, and the limits of violence as articulated by Nelson Mandela.(14)

Challenging Questions

What can we conclude from this investigation? Atrocities and acts of terrorism have always happened when there is an armed struggle against colonial oppressors who have committed far greater atrocities, and this has never derailed socialists from support of a just cause.

While Hamas cannot be reduced to a “terrorist organization” — it carries out social service functions and has a religious dimension — it has surely committed terrorist acts (starting with suicide bombings) according to the common definition: violence and intimidation against civilians for political ends. And so has the Israeli state, a hundred times more.

Marx himself regarded violence and terrorism against oppression as “inevitable” and “as useless to discuss as an earthquake.”(15) That’s why radicals don’t renounce the Haitian revolution against the French (1791-1804), or Nat Turner’s Rebellion against slavery (1831), or even the Mau Mau Rebellion against British rule in Kenya (1952-60) that killed thousands of their fellow Africans, on account of horrific violence against civilians.

Yet it is a separate matter for socialists to strategize or champion civilian murders, indiscriminate terrorism, and atrocities. Such conduct cannot be perfunctorily accepted as effective or even just necessary in advancing the cause of a new society. This includes the relegation of such deaths and brutalization to a minor issue in the way that imperialist powers commonly refer to “collateral damage.”

To me, there is nothing mysterious or hard to grasp about recognizing substantial civilian casualties as an issue to be frankly deliberated.

We know that socialists are not absolute pacificists. We maintain the right of armed self-defense, acknowledge the unfortunate likelihood that decolonization will not occur peacefully, and accept the possibility that, in military combat, individuals on one’s own side may go rogue and commit acts that one abhors.

Nonetheless, there are surely ethical matters to contemplate about targeting, or endangering, non-combatants.

During World War II, the United States took the stance that the civilians of Japan were worthy of mass annihilation by nuclear weapons because their government was committing crimes. Marxists and many others responded to this with horror at what Trotskyist leader James P. Cannon called “an unspeakable atrocity,” the intentional killing and injuring of “The young and the old, the child in the cradle and the aged and infirm, the newly married and the well and the sick, men, women, and children….”(16)

This “collective punishment” is surely what the Zionist state is carrying out at present, under the figleaf that “terrorists” are using tens of thousands of people as “human shields.” Should we now turn around and declare that “collective punishment” will bring about social justice so long as it is employed by anticolonial forces?(17)

Ethical and strategic questions are often intertwined. Atrocities carried out by rebels can produce political setbacks through the unification of the enemy and enabling it to deflect attention from its own violence. With greater resources for world-wide propaganda, the colonists can readily depict the resistance movement as barbaric and inflame its own population to perpetrate horrific reprisal.

Unnecessary brutality on the part of an anticolonial or radical movement can also create a malign culture with qualities that will destroy its future liberatory possibilities. For example, Shatz notes that the practices of the FLN — authoritarianism, top-down decision-making, killing rivals and villagers suspected of rival sympathies — played a role in post-independence repression.

Did atrocities and mass terror in the Civil War following the Russian Revolution really help the Bolsheviks, or did they pave the way to the further brutality of the Stalin regime?(18) It’s no secret that a militarized and violent state of affairs attracts people on all sides who use ideological claims but are motivated by sadism and a lust for power over others.

Sadly, it is not only defenders of the status quo who have the capacity to opportunistically compartmentalize abhorrent behavior. And yet socialists surely envision a different world, operating on different principles from those with bloodless responses to ordinary human suffering.

No doubt somewhere V. I. Lenin would be gasping in disbelief at the way that some contemporary Marxists are simplistically conflating “unconditional support” of a struggle with uncritical political backing of whatever political organization happens to be taking action.

I’m the furthest from a Lenin idolator,(19) but generations of socialists have been educated in what can be a useful distinction that is now being blurred, or at least parsed in unhelpful ways. Too often phrases from Lenin, like ones from Fanon, are evoked instrumentally, for polemical purposes.

Fortunately, we have access to a number of well-contextualized histories of Lenin and his disciples discriminating between an appropriate struggle and tactics that impede. Famously, Lenin was unforgiving in condemning the terrorist methods of the agrarian Social Revolutionary Party in Russia, even as he was thoroughly committed to proletarian revolution and understood that Czarist violence would eventually have to be met with counter-violence.

Decades later, Leninists in Great Britain were categorically in support of the Irish Republican cause but took their distance from the nationalist bombing campaigns that killed innocent bystanders. And when Leon Trotsky insisted on “unconditional defense” of the Soviet Union against imperialism, does anyone in his or her right mind think he then hushed up his merciless criticisms of its Stalinist leadership?

Moreover, “armed struggle,” supported by socialists under appropriate circumstances, can be exploited as a catchall phrase to cloud distinctions. There are many types of such activity and one can debate their appropriateness in various contexts.

Armed struggle can be the central strategy, as when an armed group tries to take over a government. There can also be an armed wing of a mass movement that provides self-defense. Or a Marxist party can have a special unit that engages in targeted military strikes.

As historian Ronald Grigor Suny explains, in the early 1900s both the Bolshevik and Menshevik factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party “were … critical of acts of terrorism,” but still open to “armed self-defense, assassinations of state officials and police spies, and expropriations of state treasure if it were tied to and contributed to the more important mass struggle.”(20)

From Shatz’s narrative of Fanon we can see the danger of adapting to an organization that began with a democratic and secular perspective but progressed to authoritarianism; one that evolved to the resurgence of patriarchal oppression and social conservatism, allowed the killing of internal and external critics, and worse.

Due to a misplaced organizational loyalty, Fanon ended up an unwitting propagandist for the political leadership that would ultimately destroy his dreams.

To be clear: No one knows what Fanon or Lenin would be saying if they were responding to current events. They lived in a different era, and a work like The Wretched of the Earth is more useful as an investigative resource than a how-to-do-it manual. At best, writings by Fanon and Lenin might provide conceptual frameworks that one can use in strategically appropriate assessments of unique situations.

The same goes for judging Hamas by the policy and practice of the FLN or ANC. One can talk in terms of analogies or comparisons, but the historical and political reference points are always distinct.

Many of us are not Third World experts and need to recognize that, in every case — Algeria, Palestine, South Africa — one faces a complicated situation. All deserve serious attention and discussion by use of knowledgeable sources that come from a range of activists who are from, or at least fully informed about, the countries themselves.(21)

To be sure, abstract Marxist formulae do not provide templates and instant answers. When workers of one nationality are participating in the state repression of another nationality, the issue of class unity becomes highly complicated.

Much of the Israeli-Jewish working class, for example, is overwhelmingly privileged in relation to Palestinians due to Zionist conquest. Socialists traditionally call for an end to oppression based on bringing together the working class of an entire region, yet the racism of the Israeli Jews and Zionist ideology is a major stumbling block. That’s why calls for Jewish-Arab proletarian joint struggle seem at present to be as utopian as believing that a democratic socialist transformation of Arab states in the Middle East will come to the rescue.

There’s no point in hiding the truth that many facts confound such redemptive scenarios. On the other hand, material conditions change, populations are not a static essence, and consciousness alters. Our task is to historicize this tragic impasse, not to reify it.

Marx famously wrote in 1852: “The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living.”(22) This is true when it comes to the paradox of supporting anti-colonial violence.

We all walk along a well-trod moral tightrope with no one exempt from accusations of hypocrisy and double standards. If we fail to remain alert to the duplication of deleterious patterns of thought and behavior, a new generation will be molded by a record of previous failures and misjudgments. That means we must sometimes engage in a corrective scrutiny of our own political fidelities and ethical boundaries, in order to avoid repeating the past instead of going beyond it.

As an alternative, we must start by disallowing such taboos as the view that defense of social revolutions or anticolonial struggles tolerates no space for substantial criticism of policies (whether they be reformist, ultraleft, or needlessly cruel). Or that expressing compassion for all children and other non-combatant victims is tantamount to betrayal or “bothsidesism.” We know too well where that kind of thinking leads.

I can’t speak to this as an authority on ethics or morality, but there is some general guidance from Ernest Mandel, a veteran of the World War II underground resistance, in his 1989 Socialist Register article on “The Case for Revolution Today”: “The essence of revolution is not the use of violence in politics but a radical, qualitative challenge — and eventually the overthrow — of prevailing economic or political power structures.”(23)

We create ourselves by the decisions we make, and gain nothing by emulating the same mentality of those we oppose with their selective empathy, euphemisms and evasions. When it comes to undoing the legacies of imperialism, the new generation of socialists has no option but to rush toward the flame of resistance and continue the fight.

In this process, however, we also must defend the norms of reasoned debate, rejecting facile ideological amalgamations and denunciations, as we collectively formulate positive alternatives. Above all, we must learn from lives of Fanon, Mandela and many others if we are to advance to the culmination of the long arc of liberation from colonialism.

Notes

- Definitions of political terms are always subject to change and debate. For purposes of this essay, I am using “anticolonial” to refer to political opposition to colonial rule and “post-colonial” to mean the temporal period after direct control. “Decolonial,” more controversial in applications, originated in Latin American scholarship and involves a focus on the lasting traces and legacies of colonialism.

back to text - These debates can be found in dozens of publications, and the purpose of this essay is not to address any specific one. A sampling of views can be found in a series of articles published by Tempest magazine: Jonah ben Avraham, “Support Palestinians when they fight, Not just when they die,” 5 November 2023; Dan LaBotz and Stephen R. Shalom, “A Response to Jonah ben Avraham’s ‘Support Palestinians When They Fight,’” 24 November 2023; Sean Larson, “Against colonial narcissism: A response to Dan La Botz and Stephen R. Shalom,” 20 December 2023; and Dan LaBotz and Stephen R. Shalom, “Once More on Hamas: A Reply to Sean Larson,” 12 January 2024.

back to text - The most esteemed book about the war is Alistair Horne, A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962 (New York: New York Review Books, 2006). Horne presents his own figures for deaths on pp.537-38.

back to text - Unfortunately, the French Socialists supported French colonial rule and the Communists, at best, were ambiguous. The most thorough record of Trotskyist and anarchist involvement available in English is Ian Birchall, ed., European Revolutionaries and Algerian Independence, 1954-1962, Revolutionary History (2012), Vol. 10, no. 4.

back to text - See the recent Amnesty International report: https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/middle-east-and-north-africa/algeria/report-algeria/.

back to text - Exactly what happened regarding rape and sexual abuse of both Israelis on October 7 and Palestinians by the IDF and settlers is still under dispute. The full story may never be known, but independent agencies are investigating, and facts must not be denied. As I write, the latest report available is by Farnaz Fassihi and Isabel Kershner, “U.N. Sees Signs of Sexual Abuse in Hamas Attack,” New York Times, 5 March 2024: 1, 9. At the same time, I recommend signing the “Open Letter” against the weaponization of sexual assault: https://stopmanipulatingsexualassault.org/#home.

back to text - As many have observed, the history of European pogroms and the Holocaust were quickly exploited to make Israeli Jews appear victims as their state reigned down terror on the stateless in Gaza. For a brilliant refutation of this propaganda strategy, see Pankaj Mishra, “The Shoah After Gaza,” The London Review of Books, 7 March 2024: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n05/pankaj-mishra/the-shoah-after-gaza

To be sure, the Holocaust was real enough and it is possible that the details of the horrors of the pogroms in Eastern Europe are not as well known as they should be. For the latter, In the Midst of Civilized Europe: The Pogroms of 1918-21 and the Onset of the Holocaust (New York: Metropolitan, 2021), by Jeffrey Veidlinger, is a must read. - However, Shatz did publish a widely-discussed response to the October 7th events, “Vengeful Pathologies,” in the 2 November 2023 issue of The London Review of Books: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n21/adam-shatz/vengeful-pathologies.

back to text - A compelling alternative interpretation of Fanon’s trajectory can be found in Gavin Arnall’s brilliant Subterranean Fanon: An Underground Theory of Radical Change (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020). Arnall’s argument is that “Fanon’s metamorphic thought is ultimately split between two distinct modes of thinking about change.” (205)

back to text - Alan Wald, “Frantz Fanon, by David Caute,” International Socialist Review (November 1974): 42-43. [This journal, which was published by the U.S. Socialist Workers Party, is not to be confused with the more recent publication (1997-2019) associated with the International Socialist Organization —ed.]

back to text - This matter is discussed by Anthony Alessandrini in the 7 February 2024 issue Los Angeles Review of Books: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/ambivalent-fanonism-on-adam-shatzs-the-rebels-clinic/. One of the examples cited is that “The Beninese writer Paulin Joachim, an acquaintance of Fanon, told [Felix] Germain that he had seen Fanon hit Josie on a number of occasions….”

back to text - Peter Hudis, Frantz Fanon: Philosopher of the Barricades (London: Pluto, 2015), 20.

back to text - These quotations from Fanon appear in a recent essay by a writer scornful of any public criticism of Hamas’s actions: https://mondoweiss.net/2024/02/the-unthinkability-of-slave-revolt/.

back to text - Recent discussions of the ANC have appeared in Dissent, World Outlook, and the Minneapolis Star Tribune: https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/terror-and-the-ethics-of-resistance/; https://world-outlook.com/2024/01/25/the-palestinian-struggle-lessons-from-south-africa/ https://www.startribune.com/to-defeat-injustice-follow-mandelas-castros-example/600314042/ This is not to suggest that the practice of the ANC was always consistent with the theory. See “ANC Apologizes for Deaths in Anti-Apartheid Fight”: http://www.cnn.com/WORLD/9705/12/safrica.amnesty/index.html.

back to text - This is cited in an informative essay on “Marxism and Terrorism” by Gareth Jenkins in International Socialism 110 (April 2006): https://isj.org.uk/marxism-and-terrorism/.

back to text - This appeared in the Militant, 22 September 1945, and is available online: https://www.marxists.org/archive/cannon/works/1945/hiroshima.htm.

back to text - “Collective punishment” is usually facilitated by the loose use of labels to demonize a group; the Right has used “terrorist” but the Left has a history of terms such as “kulak,” “bourgeois,” and “counter-revolutionary” to stigmatize populations, and of course the Stalinists used “Zionist” to persecute and execute communist dissidents and others. Referring to the killing of civilians by both Hamas and the Israeli state, Canadian activist Naomi Klein eloquently made the point that all children have the right not to be slaughtered. Naomi Klein, “In Gaza and Israel, Side with the Child Over the Gun”: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/oct/11/why-are-some-of-the-left-celebrating-the-killings-of-israeli-jews.

back to text - For a recent discussion of the mistakes of the Bolsheviks by a Leninist, see the material on violence on Paul Le Blanc’s October Song (Chicago: Haymarket, 2017), especially pp. 219-254.

back to text - See Wald, “In Defense of Critical Leninism,” Against the Current, January-February 1987: https://againstthecurrent.org/atc006/in-defense-of-critical-leninism/.

back to text - Ronald Grigor Suny, Stalin: Passage to Revolution (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 372.

back to text - Mark LeVine, Director of the Program in Middle East Studies at UC Irvine, offered in Aljazeera some useful observations on differences between Algeria and Palestine. He suggests that a strategy of military overthrow of the Zionist state, aiming for the departure of the Jewish population from the region, “could lead to a redux of the Nakba, as many Israeli politicians are now screaming for.” See: https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/10/10/fanons-conception-of-violence-does-not-work-in-palestine.

back to text - See: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/ch01.htm.

back to text - Mandel certainly held that the rulers of society would use violence to protect their interests, and that armed self-defense will be required. Nevertheless, he observed: “No normal human being prefers to achieve social goals through the use of violence. To reduce violence to the utmost in political life should be a common endeavor for all progressive and socialist currents.” Ernest Mandel, “The Case for Revolution Today,” Socialist Register (London: Merlin Press, 1989), 159-184. While the organized Trotskyist movement is long past its sell-by date, some of its writings on terrorism and violence might be revisited with some benefit. George Novack, a leader of the US Socialist Workers Party when it was still on the Left, wrote a 1970 essay on terrorism. It focused mainly on the difference between individualist and mass action, but his call to “experience” and “reason,” and conclusion that “The Marxist attitude is based on grounds of revolutionary efficiency,” are useful watchwords. See: George Novack, “Marxism Versus Neo-Anarchist Terrorism,” International Socialist Review, June 1970, 14.

back to text

to be published in the May-June 2024, ATC 230