Dianne Feeley

Posted December 27, 2021

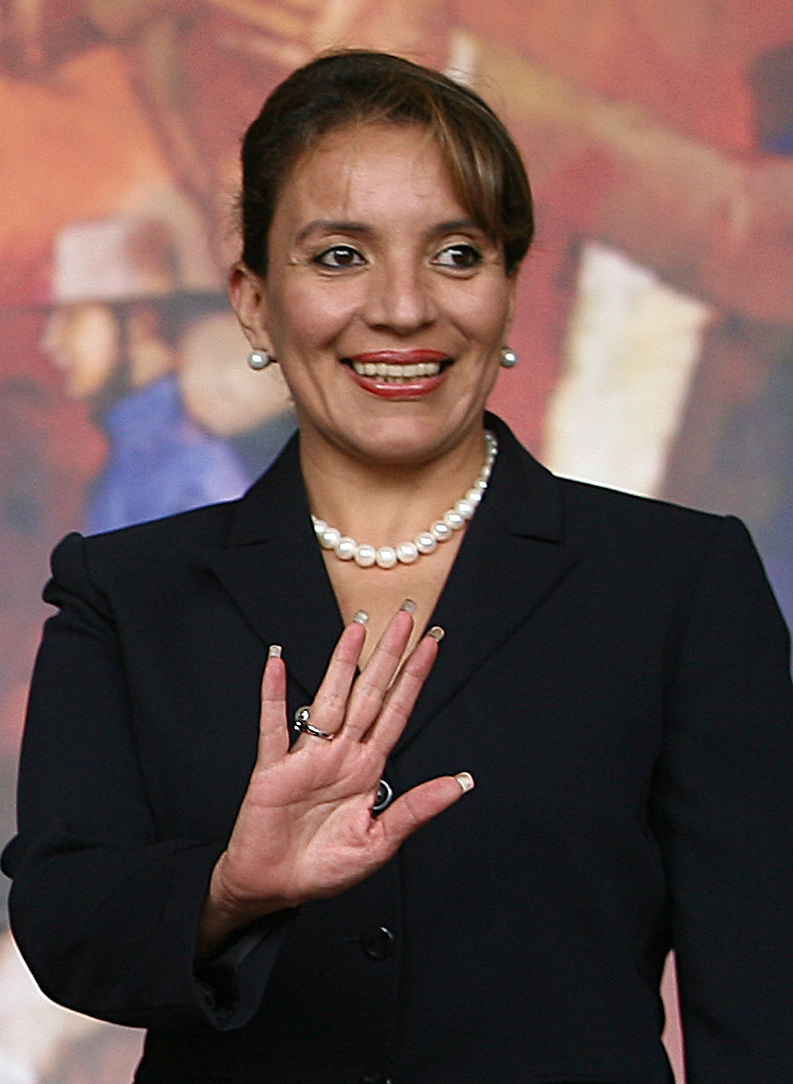

Sixty-eight percent of Hondurans turned out to vote in the November 28, 2021 elections, with 53.4 percent supporting Xiomara Castro for president. She will become the country’s first woman president, but more importantly her election is a break from the last 12 years of authoritarian regimes.

This impressive victory after the 2009 U.S.-backed military coup — followed by three stolen elections — is a tribute to the tenacity of the country’s social movements. Calling sitting president Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH) a narco-dictator, Xiomara Castro campaigned on a platform to end corruption, privatization and repression. She seeks to cut through the gordian knot of laws that has aligned the Honduran Congress and Supreme Court with the authoritarian executive branch and its military.

She also seeks to develop a foreign policy independent of Washington and to challenge the country’s draconian abortion law. But what is possible?

The Backstory

A vibrant and wide-ranging mass movement — comprised of workers’ struggles, Indigenous protests against the development of mining and hydroelectric dams, women’s and LGBTQ demands for equality before the law, and peasant/Indigenous struggles against landowners — formed at the beginning of the 21st century and now celebrates Castro’s electoral victory.

Beginning in 2003 social movements came together in a broad coalition against the Central American Free Trade Agreement and the neoliberal policies the International Monetary Fund and World Bank demanded as part of a structural adjustment program. The National Coordinating Committee of Popular Resistance (CNRP) organized a series of general strikes and national days of action.

Elected in 2005 as a member of the Liberal Party, President Manuel Zelaya eventually responded by raising the minimum wage, blocking privatizations and proposing a referendum on whether to rewrite the Constitution. This last action infuriated the country’s elite, and the military refused to deliver the ballot boxes for the referendum. When Zelaya indicated he wanted to push ahead on the referendum, the military unceremoniously escorted him out of the National Palace in his pajamas and put him on a military plane to Costa Rica.

Despite the repression unleashed by the coup, the popular movement immediately took to the streets, demanding the return of the democratically elected president and a constituent assembly to write a new Constitution. The daily demonstrations were met in the streets with tanks.

While the United Nations, many Latin American countries, the European Union and the Organization of American States (OAS) denounced the coup, the Obama Administration and its Secretary of State Hilary Clinton would not even use the word coup to describe the overthrow. Clinton, in her autobiography Hard Choices, claims that Zelaya’s removal, supported by Congress and the Supreme Court, was conducted legally, writing: “Certainly the region did not need another dictator, and many knew Zelaya well enough to believe the charges against him.”

After three attempts, Zelaya succeeded in sneaking back into the country, taking refuge in the Brazilian Embassy. Thousands flocked to the area. The military responded with water cannons, tear gas grenades and bullets, arresting hundreds and setting up makeshift detention centers in sports fields. Others were disappeared.

Despite the CNRP demand to postpone the November elections, they went ahead. Aside from a delegation from the U.S. Republican Party, there were no international observers. The National Party’s candidate Porfirio Lobo was elected president. He put an end to any mediation of land conflicts and, working with Congress president Juan Orlando Hernández, moved ahead with privatizations.

A reign of violence, corruption and terror against opposition and especially Indigenous activists defined the coup government. Later we learned that a network connecting public officials and businessmen with drug traffickers was woven into daily dealings.

The crisis brought a breakdown of the 100-year-old two-party system, whereby the Partido Nacional (National Party) and the Partido Liberal’s (Liberal Party) took turns governing. By 2011 the Liberatad y Refundación party (LIBRE) arose to become the popular movement’s electoral arm and prepared itself to contest the election two years later. LIBRE ran Xiomara Castro, Zeyala’s wife, for president, but with the election apparatus in the hands of the National Party, Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH) was declared the winner.

JOH was a fitting inheritor of the post-coup government. As president of the Congress, he replaced four out of the five Supreme Court justice with his loyalists. It has since been revealed that he and his party embezzled the country’s social security reserves to finance his election campaign.

When the scandal came to light in 2015, the popular movement took to the streets in torch-lit marches, roadblocks, occupations and a general strike. More than 500 protests spread across the country, in rural as well as urban areas. The three demands were for JOH’s resignation, criminal prosecution of the officials implicated in the scandal, and creation of an International Commission Against Impunity in Honduras, like the one that had been stablished in Guatemala.

The massive protests were able to force the president to set up an investigative body in 2016, but without the necessary independence and mandate.

Post-Coup Government Giveaways & the Murder of Berta Cáceres

Living in the poorest country in western hemisphere after Haiti, Hondurans opposed the government’s selling the country’s natural resources. The best-known struggle has been waged by the Indigenous Lenca people in defense of their land and rivers.

The government provided Desarrollos Energéticos SA (Desa) with an illegal permit to build the Agua Zarca dam on the Gualcarque River. Longtime environmentalist and feminist Berta Cáceres, co-founder and director of the Consejo Cívico de Organizaciones Indígenas Populares (COPINH, Civic Council of Popular Indigenous Organizations), built broad support for the resistance campaign. By early 2016 the surveillance and harassment of COPINH escalated to death threats, and on March 2 assailants murdered Berta Cáceres in her home. As the recipient of the world’s leading environmental award, the 2015 Goldman Prize, she was well known nationally and internationally.

In 2018 seven men, including two trained by the U.S. military in Fort Benning, Georgia, were convicted of the murder. Over the course of the trial, evidence showed that the men received orders from Desa executives. In July 2021 Desa’s president, Roberto David Castillo Mejia, was found guilty of being the intellectual author of the crime.

Castillo is a perfect illustration of the corruption and violence that descended upon the country. A graduate of West Point’s International Cadet Program, Castillo saw his opportunity and developed an empire, building eight corporations in Honduras and two in Panama.

Without experience but using his connections, Castillo received contracts from state agencies, many of which appear illegal, and sought to attract capital, beginning with drug-trafficking operations. He then went on to obtain international investments. These included export credit agencies and development banks in Norway and Finland, as well as multilateral development banks, even the World Bank.

Castillo as a businessman used his contacts to spy on and interfere with Lenca opposition to the dam project, employing the Ministry of Security, police, the military and the judiciary, in addition to his own employees and ex-employees. He perfected the military skills he learned at the U.S. taxpayers’ expense. (See Violence, Corruption & Impunity in the Honduran Energy Industry: A Profile of Roberto David Castillo Mejía on the School of the Americas Watch website. If you have trouble downloading the file, keep trying.)

The Smell of Corruption

In 2017 JOH decided to run for a second term, which is not allowed under the Constitution. But with the Supreme Court, the election apparatus, and the military in his pocket, he proceeded. Once again, LIBRE contested, this time running the popular TV sportscaster Salvador Nasralla, who seemed to be winning on election night. With 60 percent of the vote counted Nasralla had a five-point lead when a “power outage” shut down the voting system.

When power was restored, all too predictably JOH was in the lead. Outraged, protesters set up highway barricades and paralyzed the country’s transportation system. The government then suspended constitutional guarantees, and the military imposed a 6PM to 6AM curfew. Yet the demonstrations continued, and the OAS suggested that the election be rerun.

The electoral authorities, however, barreled ahead and declared Hernández the winner. U.S. President Donald Trump congratulated him as the marches, roadblocks and the nightly demonstrations banging pots and pans continued. Over the course of a 10-day period approximately 30 people were killed and 1350 arrested for curfew violations.

The popular movement continued to respond with massive street marches, road occupations and even outbursts of anti-government slogans during soccer matches in stadiums, demanding an end to the Partido Nacional’s looting of the country with their slogan, “Fuera JOH” (“Out JOH”).

During these years, many Hondurans — suffering the horrific cumulative impact of neoliberal policies, drug trafficking, political repression and the violence it all brought — sought refuge in the United States. By 2019 the U.S. border patrol apprehended 250,000 Hondurans. The next year hurricanes Iota and Eta hit, killed at least 100 and displaced 100,000. The government response was completely inadequate — as has been their response to the COVID crisis.

With JOH’s fraudulent re-election, the corruption and violence deepened, but so too did the popular movement’s understanding of the regime’s rottenness. Protests, now led by healthcare workers and teachers, challenged impending privatization legislation. Through their Platform for the Defense of Health and Education, they built a movement which had representation in every part of the country.

By the end of April 2019 demonstrations launched by the Platform spread throughout the country. They were so swift and massive that Congress shelved the planned privatizations. This emboldened the movement, and the following month there was a complete shutdown. Police went after protesters with teargas and live ammunition; at least five were killed and 30 sent to the hospital.

That fall JOH’s brother, Juan Antonio Hernández, was found guilty in the U.S. Southern District of New York on four counts, including conspiracy to import cocaine into the United States, and sentenced to life in prison. This confirmed the drug-trafficking and money-laundering charges against JOH, his family and the National Party. In fact, the trial included evidence that JOH took a million-dollar bribe from Mexico’s drug lord “El Chapo” Guzman and that the Minister of Security, Julian Pacheco Tinoco, was implicated in drug trafficking.

For the 2021 election the National Party dared to run Nasry Asfura, a close associate of JOH, while an extremely broad movement united around Xiomara Castro. Nonetheless people weren’t sure that the election wouldn’t be stolen once again. Military police in riot gear roamed Teglucigalpa, while some downtown stores boarded up their windows. Yet the election results revealed Castro’s important victory early on.

Dana Frank, a keen observer of Honduras over the years, wrote in her New Left Review Sidecar article Honduran Dreams that perhaps the visit of Brian Nicholas, Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs, to meet with top officials the week before made it clear that another fraudulent election could not take place.

Honduras: Washington’s Traditional Ally

Although Washington throughout the Obama and Trump administrations supported the corrupt and illegal governments, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken quickly congratulated Xiomara Castro on her impressive win.

U.S. administrations throughout these years have continued to train the police and military, and didn’t seem (or pretended not) to notice the increase in drug trafficking. There were no sanctions when security forces murdered and disappeared those who defended democracy.

Why was the U.S. recognition extended to Castro? Her interest in developing an independent foreign policy, recognizing Venezuela, Cuba and China, does not match Washington’s vision. On the other hand, the Biden administration is mostly concerned about decreasing the number of Central American migrants seeking asylum from violence and corruption. Clearly another four years of a rapacious government shredding public healthcare and education would only increase the number heading toward the U.S. border.

When Vice President Kamala Harris, the daughter of immigrants, went to Guatemala and Mexico last June, she announced, “Do not come.” The administration is prepared to throw some money at, and find corporations to invest in, the Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras) to slow the flow of immigrants. But the authoritarian and corrupt governments in Guatemala and El Salvador — although happy to take the money — have little incentive to root out the causes of migration.

The program of the Biden administration is far from helping an economic model that reverses privatization and rebuilds public services. It has put together $1.2 billion in investments from companies such as PepsiCo, Microsoft, Mastercard, Peet’s and Cargill and announced that Parkdale Mills will spend $150 million to build a new yarn-spinning facility in Honduras.

Most importantly, Honduras is a strategic site of the U.S. Southern Command (Southcom), which operates out of Honduras’s Soto Cano Air Base, where the Honduran Air Force Academy is located. It coordinates closely with the Honduran military, which it trains and equips. The base was a key staging area for Washington during the 1980s contra war in Nicaragua. Its main job now is to ferret out drug trafficking, at which it has failed miserably.

While Washington is willing to acquiesce to Xiomara Castro’s win this time around, the relationship between the U.S. and Honduran military continues, as will the funding. It is also very unlikely that JOH and his closest cronies and family members will face trial in the United States.

For now, the incoming government may find its hands tied by those closer to home.

A Divided Government

Honduras has been ruled by three right-wing and corrupt administrations. If Trump in four years was able to adopt executive orders and change policy in a number of departments, imagine what a regime three times as long has been able to accomplish. The Honduran Supreme Court has been replaced, and corrupt networks of drug traffickers, the security apparatus, officials and businessmen have been consolidated.

LIBRE does not have a majority in Congress, which may mean gridlock. Added to this is the reality of a debt that will put the Castro government in the position of having to negotiate with the banks and other institutions that were happy to deal with JOH. Will she have the political space to say that the debts are odious and should not be repaid?

Those who fought for justice over the last dozen years need to stand firm in their struggle to defeat the elites. If they press their demands, backed by mass mobilization, change is possible.

Note: Many thanks to Dana Frank for her reporting on Honduras over the years, and for her recent analysis of the election in New Left Review Sidecar, Honduran Dreams, 14 December 2021. I also found Honduras A Decade of Popular Resistance by Eugenio Sosa and Paul Almeda in NACLA Report on the Americas, Winter 2019 helpful.