by Ryan Haney

January 8, 2017

Refinery Town: Big Oil, Big Money and the Remaking of an American City will be available from Beacon Press on January 17th, 2017.

Steve Early’s Refinery Town is a compelling read on multiple levels. It paints an interesting portrait of Richmond, CA (pop. 110,000), a Bay Area city that is home to a massive Chevron refinery. It also works as a journalistic deep dive into contemporary municipal politics, with a cast of reformers and establishment actors clashing over approaches to problems in a city wracked by disinvestment, toxic waste, corruption, and crime.

Refinery Town excels as a case study for activists looking to build power at the local level through grassroots organizing and independent electoral work. Early, a longtime labor activist and journalist who moved to Richmond five years ago, counts himself among the reformers. His book is an invaluable documentation of their journey and a testimony of what might be possible in other cities.

Company Town

Early provides a useful background on the social and economic history of the city, from the construction of the Standard Oil (now Chevron) refinery, through the immense wartime shipbuilding operations that drew thousands of African American migrants from the South, to the eventual deindustrialization of the city beginning in the 1970s.

Central to Early’s historical background are the struggles of workers for union representation at the plant and the struggles of African Americans for equality in jobs and housing. Though great strides were made on both of these fronts, Early contends that Chevron was still able to fix the terms of the political game in Richmond—terms favorable to the maximization of their profits, and to a lesser extent the pockets of the political movers and shakers enabled by the support of Big Oil.

Unfortunately, the “company town” set-up accomplished little for regular people in Richmond, who suffered greatly as the rest of the industrial base disappeared, leaving superfund sites, poverty, and crime to take place. By 2003, the city had a miserable reputation and a $35 million budget deficit that had been carefully hidden by the outgoing City Manager.

Rise of the Richmond Progressive Alliance

More positive developments were also emerging in the early 2000s, though. A new group calling itself the Richmond Alliance for Green Public Power managed to defeat a Chevron-proposed power plant on the grounds that it would increase pollution in the city. There were also stirrings in the rapidly growing Latino community of Richmond, with a day laborer association successfully pressuring the Richmond Police Department to cease harassment of its members at an area Home Depot.

Emboldened by these victories and eyeing a 2004 election where five City Council seats would be up for grabs, area activists formed the Richmond Progressive Alliance (RPA). The RPA held a “People’s Convention,” where 300 residents set policy goals on issues that had long been ignored by elected officials, and fielded two candidates, including future mayor Gayle McLaughlin. McLaughlin, a relative unknown who was a longtime activist and member of the California Green Party, landed in fifth place and won the first seat for the RPA.

The bulk of Refinery Town is devoted to the story of how the RPA built on this victory and subsequent elections, growing its representation in City Hall (now up to five of seven councilors are RPA members) and its organization at the grassroots. It’s a story that, until now, had been largely relegated to the local news and Early’s own reporting on the pages of Labor Notes, Beyond Chron, and other left-wing media.

Perhaps it shouldn’t surprise us that the story hasn’t been told in the corporate media. After all, the RPA has been a fierce opponent of corporate power, especially Big Oil, from day one. Their candidates are required to refuse corporate donations and are held accountable to a platform drafted by Greens, socialists, and left-leaning Democrats who didn’t feel represented by state or county party structures.

Their accomplishments are certainly newsworthy by any measure:

- RPA pressure on Chevron netted the city hundreds of millions in tax revenue that would have otherwise lined the pockets of millionaire executives;

- Their work on refinery modernization gained more stringent worker and public safety than the company was initially willing to offer;

- They passed a measure to “ban the box,” fighting employment discrimination against formerly incarcerated people;

- As mayor, Gayle McLaughlin supported an overhaul of the once notoriously oppressive Richmond Police Department–today the department is a national model for “community policing”;

- The RPA introduced a measure to raise the city’s minimum wage to $12.30, the highest minimum in the state when it passed.

More symbolic, but no less significant, is the solidarity the elected officials and members of the RPA have built for area labor unions, environmentalist organizations, anti-poverty groups, and even with the people of Ecuador, who have long fought the toxic presence of Chevron.

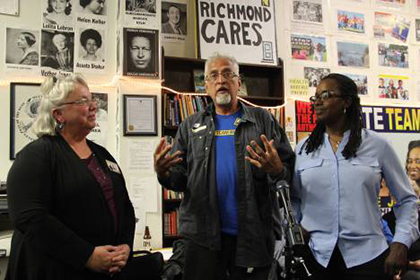

Pictured, left to right: Gayle McLaughlin, Eduardo Martinez, and Jovanka Beckles, three members of the Richmond Progressive Alliance who now serve on City Council. Photo by Tom Goulding, Richmond Confidential.

The RPA also managed to pass a powerful anti-foreclosure program, utilizing the power of eminent domain to keep residents in their homes—unfortunately, this program was effectively killed by legislation signed by President Obama in 2014 that prevented any federal role in financing mortgages of homes taken through eminent domain.

As we get into the most recent years of the RPA experience, Early offers us a very close look inside the strategic maneuverings of the RPA leadership as they respond to various challenges. For example, a controversial police shooting under the watch of a reformer police chief that the Alliance had supported created significant strain with allies in the Bay Area. Another controversy developed during the 2014 elections, when the group faced a decision on whether or not to keep an RPA candidate in a mayoral race where he might have split the anti-Chevron vote.

What’s important about these anecdotes, for those of us outside of Richmond, is to learn from the real world pressures that will inevitably challenge any experiment in independent politics. How much should one sacrifice principle in favor of preserving electoral gains? Which battles should be fought, at what time, and on whose terms? How does a scrappy, volunteer-run, left-wing coalition manage strategic relationships to its “right” within municipal institutions, while privileging its partnerships with grassroots organizations whose role it is to put constant pressure on those same institutions?

There are no easy answers, of course, but the experience is invaluable in itself. Because the RPA is not just an electoral coalition, but a grassroots membership organization, these issues are openly debated and resolved democratically. The lessons generated from that experience are generalized among the membership, rather than confined to party functionaries and professionals. Early’s transcription of these experiences onto the pages of his book greatly enriches the national discussion on independent politics.

Lessons for Independent Politics

With so many Sandernistas still hungry for a politics free of corporate influence that can expand the horizon of what’s possible, Refinery Town could not have come at a more opportune moment. Sanders proved how a social democratic platform, much like that of the RPA, resonates with working people and youth across the country.

The army of activists built through his campaign is still out there, armed with practical experience and rightfully wary of corporate influence within the Democratic Party. Furthermore, the failure of Clinton’s campaign to defeat Trump and an emboldened far right underscores the importance of articulating a working class politics, as Sanders did, that builds solidarity to defeat the one percent.

Senator Sanders himself wrote the forward to Refinery Town, claiming, “to change US politics, we need more cities like Richmond, California.” And it’s not at all hard to imagine how successful replications of the Richmond experience could one day “trickle up” into state and congressional politics, causing real trouble for the servants of capital in both parties.

But before that can happen, it will take people passionate about declaring their independence from corporate influence getting together and not just talking, but strategizing about building power that flows from the grassroots and is capable of expressing itself in government. The experience of those involved in both “realignment” strategies and third party approaches to independent politics will be essential to the conversation, as will new formations like LeftElect (in which Gayle McLaughlin and other RPA members have been involved).

It will also take getting Refinery Town into the hands of fellow activists and union members who may not yet be convinced that there’s a more promising path than continuing to support “lesser evils” or abstaining altogether from electoral politics. After the depressing victory of Trump, the story of the RPA may be exactly the inspiration they need to dream big again.

Ryan Haney is a labor activist and Teamster, based in Dallas, Texas. He spent some time in Richmond in 2014 assisting with the RPA campaigns that elected three of their members to the City Council.