Luke Pretz

March 29, 2018

Over the last six months Solidarity members in the Kansas City area have helped to build a space for anti-capitalist organizations to meet, discuss and collaborate. The Kansas City Grassroots Network (KCGN) has had its share of false starts, yet the initiative has also organized events that no one group or collection of individuals could accomplish on their own.

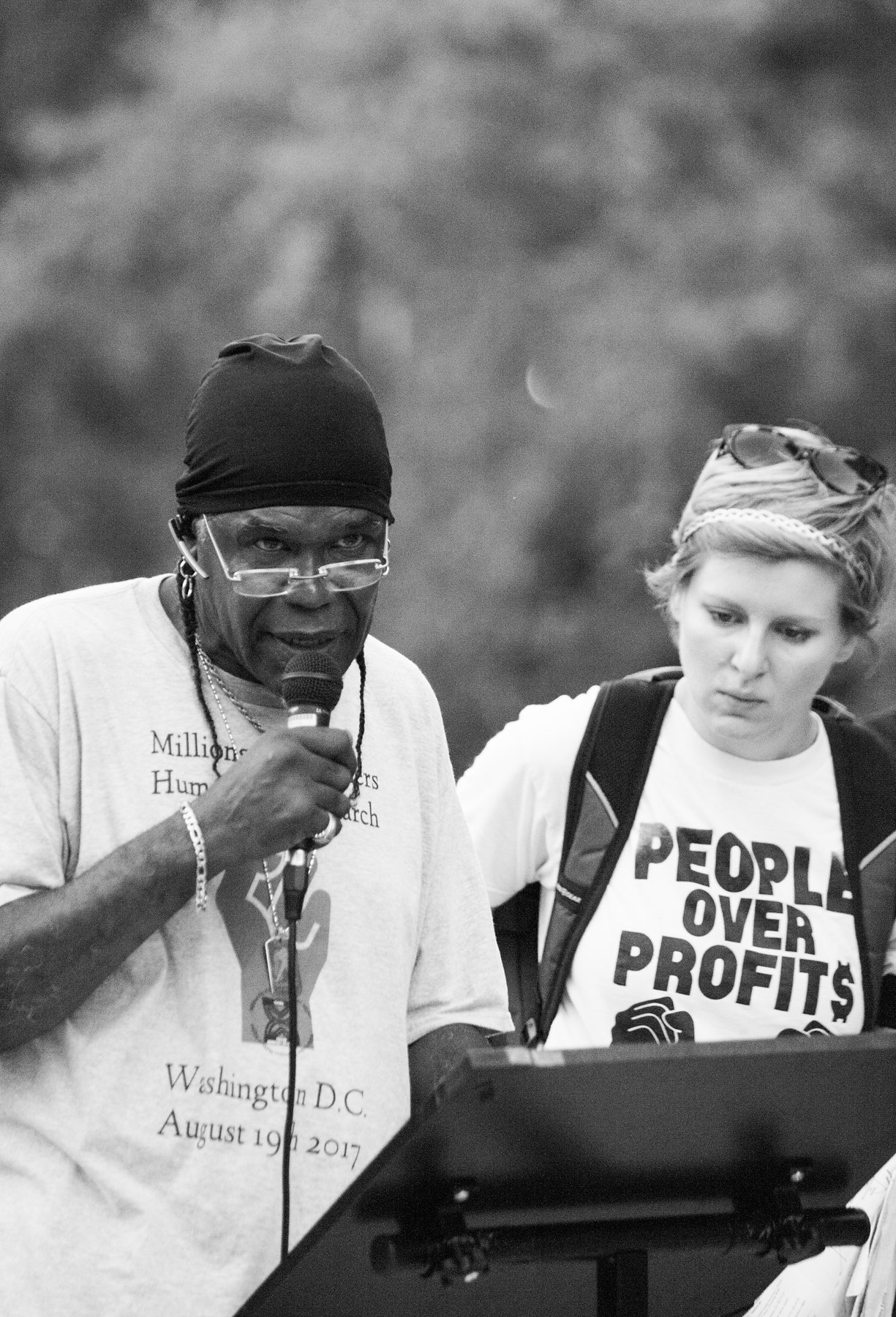

Counter-demonstrators at white supremacist Act for America rally in Kansas City. Photo courtesy the author.

Counter-demonstrators at white supremacist Act for America rally in Kansas City. Photo courtesy the author.Most importantly KCGN has provided a space for low risk dialogue, opening a window of opportunity for regrouping and refounding the left in this city. Many challenges lie ahead: ideological and strategic differences present formidable obstacles. These obstacles are compounded by the fact that KCGN’s participant organizations still lack a shared vocabulary for discussing and understanding the issues around which they seek to collaborate. Yet my focus in this report will be on KCGN’s accomplishments, which demonstrate the fundamental strength and promise of the initiative.

As I participated in developing the KCGN two concepts were central to my thinking: Regroupment, “the fusing together of the revolutionary left around a broad set of rudimentary principles”. And refoundation, the incorporation into revolutionary politics of analysis and strategies developed by a new generation of radicals not necessarily grounded in traditional socialist politics. Even if these attempts at ongoing coordination and collaboration do not produce any official regroupment, they are no doubt essential in the development of a thoughtful and non-sectarian left.

Brief History of the Left in Kansas City

As in many places in the United States, Kansas City has seen an upsurge in activity along the entire political spectrum since the 2016 presidential election. Here, this upsurge was primarily instigated by small groups and individuals inspired by recent national social movements. This activity tended to be short-lived; it emerged against the backdrop of longstanding poverty and racism, in a city where local politics has been dominated by developers and the rich.

Meanwhile, the local radical left had become severely atrophied and highly atomized since the late 1970’s. A pattern of surge and dissipation is familiar here. In the first decades of the 20th century, Kansas City was home to a variety of early leaders of the US communist and socialist movement, notably James P. Cannon, Herb March, Charles Fischer and Earl Browder. In the 1930’s there were significant labor uprisings in Kansas City meat-packing plants. To a certain degree these labor struggles managed to unite a racially diverse working class. However, the organizational gains made by socialists, communists and labor radicals rapidly dissipated as they came under the pressures of state repression and increased racial division exacerbated by discriminatory policies of city development.

In the 1960’s anti-capitalist struggle bubbled back to the surface, largely led by black power organizations like the Black Panther Party, whose local chapter was established in 1969. In the 1970s the Kansas City Revolutionary Workers Collective, a Black Marxist-Leninist organization in line with the emergent New Communist Movement, was formed. Both organizations followed the trajectory into dissolution much like their respective national movements.

There has been little sustained organizing in this city for the past twenty-five years. This is due in part to circumstances not of our making and in part to a strategy of organizing along narrow ideological lines. In terms of the circumstances that are not of our own making, the primary obstacle to building and maintaining an active left is the high degree of racial segregation that exists to this day along geographic, occupational and institutional lines. The persistent segregation in Kansas City has created a situation where social movements and radical organizing often remain highly localized and struggle to escape the geographic and racialized context from which they emerge. The tendency for organizations and groupings to prioritize party building on narrow ideological terms rather than the building of an active and growing mass, and necessarily broad, anti-capitalist movement. The strategy of building sects has resulted in organizations that are unable to realize sustained mass activity and exist in self-imposed isolation and alienation from broader social movements.

This long period of inactivity is unfortunate; the absence of a robust Left makes it difficult for the newly radicalized to find outlets to put their politics into practice. For those who are returning from inactivity or new to the city, the prospect of starting from scratch is daunting. Yet, a nearly clean slate presents opportunities as well: to learn from past attempts to advance class struggle in Kansas City, to incorporate those lessons, and to experiment more freely with new strategies.

Origins of the Grassroots Network

The Kansas City Grassroots Network formed in spring of 2017 following a lot of activity surrounding the presidential election. The initial idea for the grouping of radical organizations was brought forward by the queer feminist organization Squad of Siblings. The initial members included: the Kansas City Industrial Workers of the World, Kansas City Green Party, Democratic Socialists of America-Kansas City, Food Not Bombs, the Progressive Youth Organization, Serve the People – Kansas City, and the Kansas City Solidarity branch.

Our intent and goals were not particularly clear at first. There was a general sense that our individual efforts to build up a radical alternative would be overshadowed by liberal coalitions and groups like Indivisible that were trying to channel politics into the Democratic Party. We agreed on what differentiated us from other political groups in Kansas City: we are all dedicated to an anti-capitalist perspective and to prison abolition.

Our first joint project was a counter-protest of a white supremacist rally led by the Islamophobic group Act for America. In the process of collaborating, we developed an understanding of what our organizations were each best equipped to do and how our approaches could complement one another. We organized within our respective groups in advance of the counter-protest and reached out to Islamic community organizations, anti-racist organizations, and the broader community.

On the day of the counter rally we managed to bring out a crowd of over 200 people, despite short notice, overwhelming police presence, and the presence of an armed right wing militia, called the 3 Percenters. Our speakers connected the dots between Islamophobia, racism, imperialism and the capitalist system as a whole, and they won the attention of local television and print news media, which ran extensive quotations from the proudly eco-socialist Kansas City Green Party. More importantly, the Kansas City Grassroots Network organizers won the trust of activists unaffiliated with the group. When the police took down the barricades, the counter-protesters remained, thus ensuring that the white supremacists affiliated with Act for America left knowing that we were not intimidated by them .

Building Momentum and Digging Deeper

In the months since the counter-rally the Grassroots Network has continued to meet regularly. One of our most successful actions was a de-carceration rally and tour of the Jackson County prison system led by Missouri Citizens United for Rehabilitation of Errants, a criminal justice reform organization. The tour and rally was led by a formerly incarcerated person who had gone through Jackson County’s criminal justice system. We stopped at the jail, courthouse, processing facility, the juvenile court house and a number of other buildings.

Speakers at the decarceration rally. Photo: Suzanne Corum Rich

Speakers at the decarceration rally. Photo: Suzanne Corum RichAt each stop our tour guide spoke about the ways that the prison system was corrupt and biased against the interests of working class people, especially people of color and women. Each participating group was allotted time to speak; at the end of the day organizations exchanged contact info and discussed next steps.

Inspired by the success of our last few actions, The Kansas City Grassroots Network now seeks to build towards longer-term campaigns. We have started to deepen our discussions about what we are, where we agree, and where we may still disagree. These conversations have strengthened the commitment of member organizations to the project. Conversations have focused on broad points of agreement, such as what the liberation of oppressed nations, LGBTQ persons, women and other oppressed groups means and looks like materially. Those conversations have helped to dispel a lot of the myths surrounding ideological traditions. This hardly means that we have found that anarchists, democratic socialists, unaffiliated leftists, Marxist-Leninists, Maoists, Trotskyists, and those who are still developing their politics are all the same or that the differences are meaningless. Rather, many of us have come to see that there is a path forward based around a broad set of revolutionary points of agreement and that we can act together despite these differences. In fact, a number of organizational representatives, including myself, have come to understand that our different ideological perspectives combined with our common commitment to working in concert with one another present a wide and complementary set of tactical and strategic paths.

One of the biggest challenges that KCGN has faced is the free movement of groups in and out of the network. This issue has cropped up because we have not established any membership criteria beyond agreement on the points of unity: there are no clear expectations of participation.

With intermittent participation in the network, organizations can be left out of logistical conversations about upcoming events and campaigns that are in development. While there are immediate consequences of missing logistical conversations there are also longer run consequences that arise out of missing conversations about ideological and strategic differences. Missing such conversations means missing opportunities for developing a shared vocabulary that prevents future misunderstandings. More importantly, missing conversations that dig deep into the differences among us misses an opportunity to uncover the ways that apparently contradictory strategies can be combined to form a more cohesive whole. In response, we have sought ways to continue collaborating even if in a more limited capacity. We regularly check in with absent organizations and make good faith attempts to find out what they are planning and how KCGN can help.

KCGN is now developing a campaign focused on ending cash bail and more broadly, pre-trial detention and the abuses committed by the police and the Kansas City criminal justice system. In the process of developing a set of demands and a plan to realize them, new and more complicated questions have come up around the nature of movement building and challenging power. Many of these differences in analysis are remarkably similar to those of past attempts at left collaboration, such as single versus multi-issue campaigns and whether or not and in what ways do we include liberal organizations. Our responses to these internal challenges have changed over the course of the last year. Rather than walking on eggshells in the hopes of preventing a collapse of the network, we have begun to directly engage in good faith. When differences arise, we ask ourselves “does this preclude us from working towards the same goals?” and “can our differences in strategic outlook coexist in pursuit of those goals?”

Summing up

Helping to build and sustain the Kansas City Grassroots Network has been an overwhelmingly positive experience. Individually, it has restored my confidence and optimism for the revolutionary project to which I have dedicated much of my adult political life, a project based on the construction of a broad working-class movement in opposition to capitalism and the oppression that is part and parcel of that system. The Grassroots Network has been a success in organizational terms: we have constructed a non-sectarian anti-capitalist movement.

We are demonstrating to ourselves and to many in Kansas City that leftists of different stripes can collaborate on a regular basis, developing stronger and less adversarial relationships with one another. Because of our ongoing and deepening commitment to a shared vision, we have begun to create a common vocabulary that fosters conversations rather than conflicts and creates the basis for unity in action. Most importantly, this project has illustrated that opportunities exist for building a more unified left and has helped to plant the seeds for new attempts at intentional collaboration and conversation.

Luke Pretz, a member of Solidarity, lives and works in Kansas City, Missouri where he is active in the Kansas City Green Party and radical popular economics education.