by Jase Short

August 12, 2013

Traditionally there are two major styles of presenting a science fictional future. In one mode, class distinctions and conflicts over racial and national oppressions have melted away into a bright, technology-driven progress with sleek, clean spaces dominating the presentation. In the other mode, technological progress continues to leap ahead of social progress and all of the accumulated oppressions of past civilizations continue to dominate the daily lives of the vast majority in a world presented as something like a toxic slum. Neil Blomkamp’s new tale of planetary inequality falls squarely in the latter category.

Recalling the best Science Fiction of the 1970’s with its sharp political edge and dystopic flavor, Blomkamp’s Elysium manages to be a thoughtful fantasy reflecting the current state of the world and a thoroughly enjoyable sci-fi action film all at once. Delving into issues spanning health care, immigration, ruling class factional struggles and more, Elysium paints a picture of the future by exaggerating the features of our own world. In fact, when asked by Entertainment Weekly if the film represents what Blomkamp thinks Earth will be like in 140 years, he responded, “No, no, no. This isn’t science fiction. This is today. This is now.”

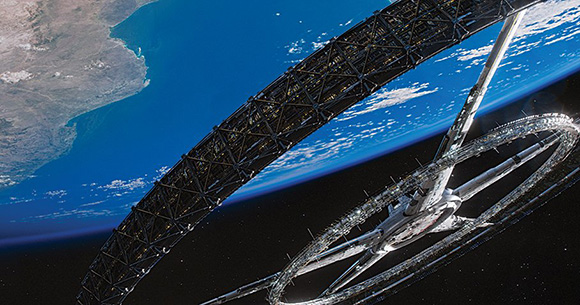

The basic premise: the year is 2154, the population of Earth is ravaged by economic and ecological catastrophes. The wealthiest have taken refuge on a giant space station orbiting Earth run by robot butlers and guards, offering them clean air and almost magical healthcare technology. One can no doubt see the contours of the current world system within this framework, both within particular countries and between the core capitalist states and their oppressed periphery. Indeed in order to capture this dynamic, principal photography was done in the poverty-stricken Iztapalapa district in Mexico City to capture the scenes of 2154 Los Angeles, while Elysium station was captured almost entirely by CGI and filming in both Vancouver and the wealthy Huixquilucan-Interlomas suburbs of Mexico City.

The casting of Matt Damon in the lead role implies two strategies by Neil Blomkamp. It is immediately obvious that on one level the casting of Damon was a marketing strategy: in a time in which only sequels or established story lines are green-lit by big studios, attaching a big name actor to a new story is a sure-fire way for studios to ensure that they recoup their profits.

On the other hand, the choice of Matt Damon represented a clear attempt to solidify the film’s political credentials. Damon has starred in several political roles, including his roles in Good Will Hunting (with a screenplay by Damon, and in which he infamously describes why he would never work for the imperialist U.S. government), the anti-War on Terror film Syriana, and recently the anti-apartheid Invictus.

The Hollywood actor has distinguished himself from his peers by openly criticizing President Obama: “I’ve talked to a lot of people who worked for Obama at the grassroots level. One of them said to me, ‘Never again. I will never be fooled again by a politician.’ You know, a one-term president with some balls who actually got stuff done would have been, in the long run of the country, much better.” Damon is also famous for his speech in 2011 defending teachers against Democrat-sponsored education “reform” at a Save Our Schools rally in Washington D.C. That speech is particularly memorable due to the viral video in which he angrily mocks the libertarian Reason.tv for their coverage of the teachers’ struggle.

That Blomkamp is interested in a left-wing science fiction with relative creative control is no secret in the film industry. Responding to the Danish website Filmz on why he turned down an offer to direct the third installment of the blockbuster Star Trek reboot, Blomkamp said, “Would I be able to make the ‘Star Trek’ film I want? Probably not, and therefore I have no desire to make it.” In an interview with filmschoolrejects.com, Blomkamp explains why he did not push for the “PG-13” rating that could have scored more profits, “I’d rather work on a two million dollar film where I can do what I want instead of a 700 million dollar film that’s not what I want.”

In fact, his previous film District 9 was received by mainstream audiences as a serious critique of racism, conjuring images of apartheid, the Israeli occupation of Palestine (and the American occupation of Iraq) as well as the oppression of immigrant populations. Though critics on the left received the movie as racist in its portrayal of “the Nigerians,” gangs run by Nigerian immigrants in South Africa who stand in for all of Nigeria to many audiences, the mainstream response to the film was focused on the ways in which the treatment of the aliens mirrored oppressions in the real world. In a sea of Michael Bay hack pieces and shallow superhero films, this was seen as an attempt to restore the critical edge to science fiction.

The premise, musical score and design all recall the sequence of science fiction films spanning the 1970’s through the early 1980’s that paint a bleak picture of a future corporate dystopia, including Soylent Green (1973), Logan’s Run (1976), Alien, (1979) and Blade Runner (1982). New composer Ryan Amon even opens the film with a direct homage to the traditional sounds of 1970’s electronic music, setting the mood for the rest of the film.

In terms of storytelling, Elysium is quite simply a kind of working class fantasy about a wronged man who heroically rights the wrongs of the class system. Regrettably, the fantastic film work involved in this production stops at the level of the world building and then enters into a more traditional form of story-telling. Nevertheless, it accomplishes this traditional tale using less common plot devices and openly left-wing themes.

Damon’s character Max is an ex-convict on parole who works at a military-industrial factory. Ironically, Max works on an assembly line constructing the very police robots that so often oppress him. Suspected of wrong doing while waiting in line for the bus to work, Max is ruthlessly beaten by the robo-cops and commanded to visit his parole “officer.” Max then journeys to the overwhelmed, unsanitary disaster that passes for a local hospital (quite different from Elysium station’s immaculate “re-atomizer” pods that fix every broken bone, every facial disfiguration and every kind of cancer imaginable) to be patched up. When he finally makes it to his parole “officer,” it turns out that it is a rude automated speaker attached to a somewhat comical looking human form. Max experiences what most people do with their parole officers: a lack of empathy and a hard-nosed assumption of the parolee’s guilt.

The plot is then driven forward by the unsafe working conditions and cruel management of the industrial plant where Max works. He is commanded to enter a potentially radioactive space in order to keep his job, and when he does he is subjected to a lethal dose of radiation poisoning. Max’s epic journey to reach the Elysium station’s healthcare technology then drives the rest of the film.

Aside from unequal access to healthcare services, the film also deals with the machinations of ruling class factions struggling for their own hegemony of the state apparatus, in this case control over Elysium station and its automated system of rule. President Patel, masterfully portrayed by Faran Tahir, represents the liberal, humanitarian wing of the ruling class. He is outraged when Defense Secretary Delacourt (Jodie Foster) orders the destruction of ships carrying undocumented migrants to Elysium station and instead wants them to be quietly seized and deported. Delacourt, on the other hand, sees this as weakness, plays the rhetorical “we must protect our children” card to justify her ruthlessness and employs dirty war tactics to carry out her will in the typical fashion of a “deep state.”

On top of this conflict between what is essentially liberal-humanitarian class rule and neo-conservative class rule, the last quarter of the film introduces an almost fascistic twist by the agents of the dirty war, which carries the same resentments against the elite as the oppressed masses of Earth coupled with a sadistic will-to-power agenda which smacks of opportunism. The struggle over who will control the state apparatus is ultimately a struggle over deciding who will gain access to the miraculous technology of Elysium station, particularly its coveting healthcare services. Without spoiling the end of the film, it is important to note that in the form of Max and a gang of futuristic migrant-smugglers the masses enter the struggle as well.

Robotic police officers and drone weaponry dominate the repressive state apparatus of Elysium station, providing a terrifying image of what our future could hold. The horrors visited upon the victims of police brutality today are magnified by an automated system of capriciousness, mirroring the guilty-by-profile approach of modern day policing, from the stop and frisk policies of New York to the whole range of other forms of permanent police violence against communities of color. However, the struggle over the automated state apparatus is also a struggle over the programming of the drone warriors themselves.

Elysium is an excellent modern day fantasy epic. It represents what is likely the best political standpoint possible in a $90 million dollar Hollywood blockbuster. The casting of a white, big named actor in a role that clearly should be reserved for a person of color (just watch the film and note Max’s immediate circle) is just one of many regrettable sacrifices demanded by the Hollywood profit machine. In spite of the fantastic world building and themes of social critique, it is an action film in which a solid half of the film is dominated by CGI spectacles.

On the whole, there is much to be praised about this film and the social reality it represents, particularly for committed advocates of social justice. In a genre currently dominated by fantasies of privileged billionaires saving the world (Iron Man, The Dark Knight), it is a welcome change of pace for a band of working class individuals to do the saving instead. Come for the action, stay for the social critique. The film has been referred to by Newsmax as “sci-fi socialism” and “political propaganda,” by The Hollywood Reporter as “politically charged flight of speculative fiction” and described by Variety as such:

[One of the] more openly socialist political agendas of any Hollywood movie in memory, beating the drum loudly not just for universal healthcare, but for open borders, unconditional amnesty and the abolition of class distinctions as well.

With endorsements as powerful as that from such notable partisans of Hollywood drivel, what’s not to like?

Jase Short is a member of the middle Tennessee branch of Solidarity, and on the editorial board of Against the Current. He is an avid fan of sci-fi and monster films.

Comments

One response to ““Elysium”: A Working Class Fantasy”