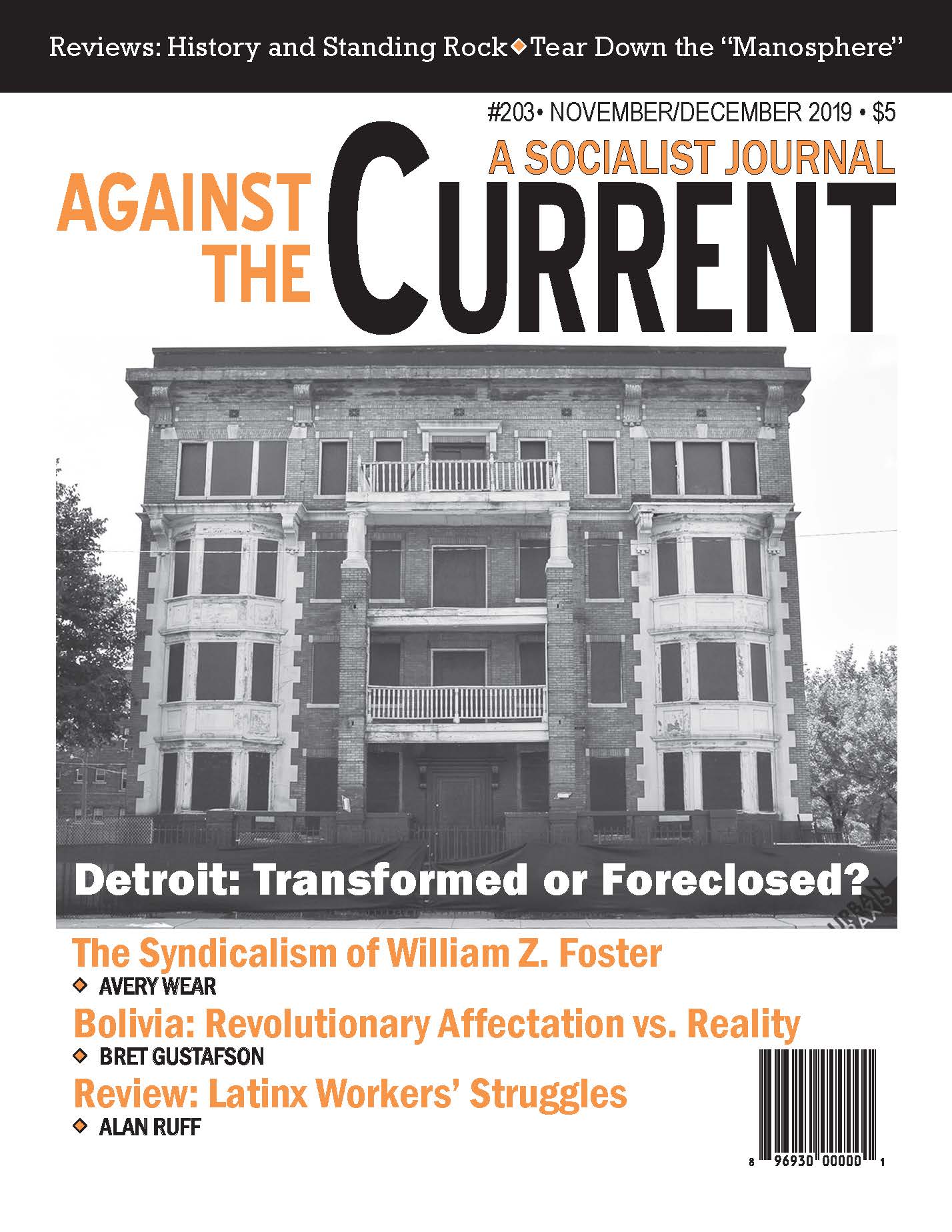

Against the Current, No. 203, November/December 2019

-

Impeachment and Imperialism

— The Editors -

Detroit Foreclosed

— Dianne Feeley -

An Overview of Detroit's Affordable Housing

— Dianne Feeley -

Thoughts on Bolivia

— Bret Gustafson -

Viewpoint: Defeating Trump

— Dave Jette -

Which Green New Deal?

— Howie Hawkins -

Howie Hawkins' Statement on Presidential Run

— Howie Hawkins - Radical Labor History

-

Introduction: William Z. Foster and Syndicalism

— The ATC Editors -

William Z. Foster and Syndicalism

— Avery Wear - Reviews

-

Voices from the "Other '60s"

— David Grosser -

New Deal Writing and Its Pains

— Nathaniel Mills -

Latinx Struggles and Today's Left

— Allen Ruff -

Tear Down the Manosphere

— Giselle Gerolami -

Turkey's Authoritarian Roots

— Daniel Johnson -

Remembering a Fighter

— Joe Stapleton -

History & the Standing Rock Saga

— Brian Ward - In Memoriam

-

In Memoriam: Hisham H. Ahmed

— Suzi Weissman -

In Memoriam: William "Buzz" Alexander

— Alan Wald

Avery Wear

IN THE 1930s, U.S. union membership leapt forward, general strikes and sit-downs won strings of victories, welfare and labor laws were passed, and the mass-production heart of the economy got organized. Anti-capitalists in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and Communist Party proved the value of marginalized methods: direct action, mass democracy, and struggle against race and sex discrimination.

But “Labor’s Giant Step” was not just a break from the past. The 50-year-old American Federation of Labor (AFL), not just the new insurgent Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), provided organizational scaffolding for the advance. And the CIO itself, despite its rebellious ranks, stayed under John L. Lewis’ established leadership. This conflictual mix of radical and conservative reflected both the prior accumulation of forces on each side, and decades of emerging strategy on the Left.

Many accounts rightly point to the revolutionary Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) as pioneer of the tactics and incubator of the personnel vital to the breakthrough. Marxist and socialist parties played important roles as well. An almost forgotten strand, however, includes the syndicalist period of William Z Foster.

At first glance Foster’s long career — forming a series of short-lived union reform groups, heading two big organizing drives that ended in defeat, ultimately leading the Communist Party into 1950s decline — promises no great lessons. Yet Foster’s circle did more in the 1910s and ‘20s to develop strategies that bridged the old and the new than did much larger forces.

Foster’s packinghouse and steel campaigns blazed a path to the successful unionization of basic industry; he developed a method for revolutionary work inside unions; and he began an organizational tradition for that work that continues today. Foster prefigured united front methods, rank and file caucuses, and revolutionary organizational forms before they had names.

The syndicalism associated with Foster, despite apparent failure, was a key bridge from a workers’ movement rendered archaic by capitalist restructuring, to one audaciously resurgent.

Industrial Transformation and Turmoil

Unions formed in the United States even in the eighteenth century. (Foner vol. 1, 70. References are listed at the conclusion of this article — ed.) But the modern labor movement dates from the 1880s — the decade of the Haymarket martyrs, the Knights of Labor, and Samuel Gompers’ Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions, later renamed the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

Unlike the Knights, who organized across industry regardless of specialization, the AFL practiced old fashioned craft unionism. AFL unions also looked backward in their frequent refusal to admit Black, women and/or immigrant workers. For these reasons, IWW members derisively termed the AFL the “American Separation of Labor.”

Craft unions, with their membership of skilled and better-paid workers, had often successfully leveraged their members’ monopoly on job knowledge in the age of small-shop manufacturing. But by the 1890s that age was ending due to technological advances. The reorganization that accompanied the concentration and centralization of capital led to the creation of modern corporations.

“Scientific” management, involving deskilling of tasks and intensified supervision, undermined the skilled trades and swamped craft employees in the factories with semi- and unskilled workers. Twenty million people immigrated to the United States from 1880 to 1920, feeding manufacturing’s growing demand for unskilled labor.

With a fast-expanding national market and a fledgling U.S. empire abroad, most of the twentieth century’s corporate giants formed in this period. General Electric, US Steel, the meatpacking oligopoly and others at first made deals with the craft-unionized minorities in their new plants. But starting in the recession of 1903, they flexed their muscles.

Corporate employers’ associations and small-town middle-class Citizens’ Alliances routed strikes and broke the unions in heavy industry. Two of the once powerful craft unions reduced to impotence were the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen, defeated in a strike in 1904, and the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers, similarly routed in 1909.

Workers resisted the “new industrial discipline” with or without, and sometimes against, the unions. A “New Unionism within basic industry” emerged as a decade of worker unrest began in 1911. (Montgomery, 101) Between 1911 and 1920 union membership grew by more than 250%, from 2.3 to five million workers. (Wolman, 2)

Each year of U.S. involvement in World War I saw more than a million workers striking — more than had ever struck in any year before 1915 — peaking in 1919 with more than four million workers on strike. (Montgomery 97. The rest of this section draws on Montgomery’s essay — AW)

This defied the AFL’s official wartime “no-strike” pledge. In 1920 7.4% of strikes, and 58% of strikers, acted without union sanction. According to historian David Montgomery, this “New Unionism” fed off a twin revolt of skilled workers defending their control of the work process, and of unskilled and immigrant workers for better wages and against scientific management. (The IWW and the Socialist Party opposed the war; many of their leaders were jailed.)

These struggles in the new mass production industries, often involving AFL unions, were in many cases led by socialists and revolutionaries. But lacking a fully formed industrial and political leadership reflecting the new militancy, most strikes “ended in total defeat.” (Ibid., 94)

Nor was membership growth consolidated — from its peak of five million in 1920, union membership had declined to 3.4 million by 1929. (Bernstein, 84) The old craft exclusionist and racist policies of the AFL, not to mention its commitment to a business union model, weighed heavily.

Left union strategy

Anarchists and Marxists helped lead the 1880s labor movement, especially in Chicago, where the International Working Peoples’ Association (IWPA) built a mass eight-hour day movement admired by revolutionaries worldwide. From at least the time of the Knights of Labor, socialists recognized the necessity for industry-wide unions to confront the emerging factory system using broad class (not mere craft) struggle.

Eugene Debs’ short-lived American Railway Union (ARU), which led dramatic mass organizing drives and strikes in 1894-5, showed the potential of the industrial form of organization (despite the ARU’s dangerous failure to break with segregation). But the ARU experience also committed Debs and others to bypassing the craft-oriented AFL to start new unions — what was termed “dual unionism.”

Daniel DeLeon of the Socialist Labor Party (SLP) initially argued the alternative proposition that revolutionaries should “bore from within” existing unions. For DeLeon, unions should not only lead the fight against capitalism, but also should take over the administration of industry and government after revolution. (Kipnis, 13-16)

Though such notions would become foundational to the international movement known as syndicalism, the fiercely “orthodox” Marxist DeLeon differed from syndicalists in insisting on propagandizing through independent socialist participation in bourgeois elections. William Z. Foster claimed to have read all of DeLeon’s pamphlets, calling him “the Father of American syndicalism.” (Barrett, 31)

But DeLeon changed course before giving “boring from within” a real historical test. In 1895 he led the SLP out of the AFL after losing a convention leadership fight. The SLP began attacking the AFL as a corrupt counter-revolutionary organization of “labor fakers.” They formed their own union federation — the Socialist Trades and Labor Alliance — which lasted for ten years of revolutionary purity and utter futility.

The SLP faded after Debs’ Socialist Party (SP) entered the field in 1900. (Kipnis, 104) The SP grew into the first mass party of U.S. socialism. SP members of its Right and Center wings, like Max Hayes and Morris Hillquit, worked to influence the AFL from within. Their reformist goals were to pass union resolutions favoring social ownership of the means of production, and endorsements for SP electoral candidates.

Pursuing these aims meant, for the SP right and center, accommodating to the backward policies of the AFL. The SP’s influential Left wing, including Debs and Western Federation of Miners’ leader “Big” Bill Haywood, reacted against this. In his speech at the IWW’s founding, Debs said the AFL’s role was to “chloroform the working class while the capitalist class go through their pockets.”

Debs and Haywood enthusiastically supported the founding of the IWW in 1905. DeLeon and Haymarket anarchist Lucy Parsons joined them.

Foster and the IWW

Founded in 1905 amid enthusiasm for the first revolution in Russia, the IWW declared in the preamble to its constitution, “Instead of the conservative motto of ‘a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work,’ we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword ‘abolition of the wages system.’”

In addition to gaining the support of the leading worker revolutionaries of the day, the new organization also attracted the established Western Federation of Miners and United Metal Workers’ unions. All wanted a militant alternative to the class-collaborationist AFL and set out to create “one big union” to embrace the whole working class.

Through a general strike “the workers of the world (could)…take possession of the means of production.” Organizing on industrial instead of craft lines meant coping with “the ever-growing power of the employing class” by enabling “all its members in any one industry” to strike together. But it also meant revolutionary goals: “It is the historic mission of the working class to do away with capitalism…. The army of production must be organized…to carry on production when capitalism shall have been overthrown.” (IWW Constitution, Preamble)

IWW organizers, known as Wobblies, prioritized direct action. They leveraged their strength by sending their itinerant membership to wherever mass campaigns popped up. Struggles often took on the dimensions of local uprisings. Aiming to unionize the unskilled and the skilled together, they brought anti-racism into the highly fractured working-class cultures of the time.

For these reasons the Trotskyist ex-Wobbly James P. Cannon in his history of early American Communism wrote, “In action the IWW, calling itself a union, was much nearer to Lenin’s conception of a party of professional revolutionaries than any other organization calling itself a party at that time.”

Despite a promising start with some 40,000 members according to Vincent St. John, the IWW never seriously challenged the AFL for leadership of the union movement, nor did it (despite leading impressive strikes) succeed in bringing lasting organization into mass production. By the time William Z. Foster joined the IWW in 1909, it had lost its largest founding union, the Western Federation, and had suffered other splits.

Foster’s Early Years

Born in 1881, Foster grew up poor among pro-labor Irish nationalists in Philadelphia. (Much of the biographical information on Foster’s life comes from Barrett and from Johannngsmeier 1994.) In 1895 the street gang he belonged to (the Bulldogs) destroyed streetcars in support of strikers.

Starting in 1900 Foster was already living as an itinerant laborer. Between then and 1916 he traveled 35,000 miles hopping boxcars across the country. He worked “logging, sawmills, building, metal mining, railroad construction, railroad train service, etc.” He even worked for a winter on a cargo sailing vessel, sailing “one and a half times around the world.” (Foster 1970, 13, 12)

Foster lived and worked in Portland, Oregon from 1904-07. There he worked with the SP Left around Tom Sladden, who argued that unskilled workers, not middle-class elements, should lead the Socialist Party. Laid off in Portland, Foster found work on Seattle’s railroads.

Hermon F. Titus led SP Left factional struggles there, expelling middle-class advocates of electoral alliances with Democrats. Titus’s politics anticipated Foster’s evolution: won over by DeLeon’s advocacy of revolutionary industrial (as opposed to craft) unionism, Titus nonetheless joined the SP instead of the SLP, as he rejected the dual unionism of the IWW.

Titus and his followers walked out of the 1909 State SP Convention in Everett Washington, charging that right-wing reformists stole the leadership. The Party’s National Executive sided with the Right, so Titus, along with the Workingman’s Paper, split away.

Soon after, Foster went to Spokane, Washington, to cover an IWW free speech fight for Titus’ Workingman’s Paper. Day laborers had to buy mining and lumber jobs from contractors. Among other abuses, contractors sold non-existent jobs. The IWW organizing campaign employed a favored tactic: using street speakers to recruit, propagandize, and if necessary fill the jails to dramatize the lack of free speech rights.

In Spokane, Foster found thousands of workers in a defiant battle at the center of city life. (Foner vol. 4, 180) Several years in the SP, a vehicle (even for the Left wing) more for electoral than grassroots activity, had never exposed him to class struggle on this scale.

Police jailed him for 40 days on December 6, 1909 for watching an IWW soapboxer. Wobbly prisoners were energetic and well organized. They chose Foster for the three-man committee that negotiated the partially victorious settlement with the Mayor. (Foster 3/12/1910, 1)

“It was chiefly disgust with the petit-bourgeois leadership and policies of the SP that made me join the IWW,” Foster would later write. In joining he became a syndicalist, believing trade union action and not political parties led to revolution. “The paralyzing reformism of the SP (convinced me) that political action in general was fruitless.” (Foster 1970, 15)

He now believed in “the possibilities of direct action” as in Spokane, “especially the marvelous effectiveness of the passive resistance strike.” He wrote to the Workingman’s Paper that “it has convinced me that it is possible to really organize the working class.”(1)

So committed was Foster to these new principles that he decided to deepen his knowledge with a 1910 trip to France to observe the world’s leading syndicalist organization, the Confederation General du Travail (CGT). He wrote to Titus, “I am on my way to a country where I should learn a little.” (Barrett, 43) What he learned on the trip would lead him beyond the IWW.

Syndicalism Toward Revolution

Socialists attained mass influence in Europe in the two decades after founding the Second International in 1889. The Second International’s parties and allied union federations formally espoused Marxism. But the unions, run by full-time bureaucrats with economic interests distinct from the rank and file, saw themselves as auxiliaries to the socialist parties. They downplayed or opposed militant bottom-up action.

The parties, in turn, increasingly emphasized elections over revolution. They won seats in local and sometimes national governments (France’s Millerand in 1899), but in doing so generally betrayed their principles and members. “In Western Europe revolutionary syndicalism…was a direct and inevitable result of opportunism, reformism, and parliamentary cretinism (in the socialist movement),” wrote Lenin. (Darlington, 57)

But while Foster and other syndicalists agreed with those criticisms of the Second International (of which the SP was a member), they also absorbed unique positive revolutionary concepts from syndicalism. When many later rallied to the Russian Revolution and became Communists, a sophisticated synthesis resulted from the infusion of syndicalism into Marxism.

Between 1905 and 1920, not only French but Spanish, Irish and Italian syndicalist federations often led their countries’ union movements. Observing this, Foster rather mechanically theorized, “The natural course of evolution for a labor movement…is gradually from the conservative to the revolutionary.” (Foster and Ford, 43)

Any Marxist would agree with the assertion that united actions, even limited strikes, educate and organize workers, creating conditions for radical consciousness to develop. The early 20th century rise of syndicalism was contingent on the general labor upsurge of the time. (Darlington, 49)

Ralph Darlington lists eight elements shared by the major syndicalist movements of the period, including the CGT and the IWW (though at the time the IWW considered itself “industrial,” not “syndicalist”). These were (1) “Class-Warfare and revolutionary objectives,” (2) “Rejection of Parliamentary Democracy and the Capitalist State,” (3) “Autonomy from Political Parties,” (4) “Trade Unions as Instruments of Revolution,” (5) “Direct Action,” (6) “The General Strike,” (7) “Workers’ Control,” and (8) “Anti-Militarism and Internationalism.” (Darlington, 21)

In his 1913 pamphlet Syndicalism Foster brought out two other principles common to the movement internationally. First, “Great strikes break out spontaneously and … they spontaneously produce the organization so essential to their success.”

Luxemburg (1906) and Lenin (1902) similarly welcomed the necessarily spontaneous breakthroughs in struggle with which revolutionaries must engage (without concluding that organization would emerge so spontaneously), but they were in a small minority in the Second International.

Second, quoting the 1906 CGT Convention, Foster wrote, “the fighting groups of today will be the producing and distributing groups of tomorrow.” In other words, unions become the bodies that manage the economy post-revolution.

By the 1920s Foster and thousands of radicals who would go on to organize the struggles of the 1930s had refined and modified these principles. In particular, they viewed syndicalist anti-political tendencies as one-sided. But the basic theme of bottom-up worker mass action remained.

Today syndicalists are usually associated with anarchism (“anarcho-syndicalism”). In Foster’s time, anarchists vied within syndicalism for influence against both Marxists and pure-and-simple unionists.

Anarchists worked with Marxists and others in the IWW. In Ireland and Britain, anarchists had no significant syndicalist role. But anarchists dominated the heroic years of the Spanish CNT, played a strong role in Italy, and ran the French CGT intermittently.

Foster acquainted himself with Pouget, Yvetot, and Herve, anarchist radicals in the CGT. (Barrett, 44) He became a virtual anarchist, “accepting on principle the anarchist positions…on neo-Malthusianism [the belief that workers should abstain from having children —AW], marriage, individualism, religion, art, the drama, literature etc.” In Syndicalism he wrote, “Syndicalism has placed the Anarchist movement upon a practical, effective basis.” (Foster and Ford, 31)

Foster’s early writings from France breathed a quasi-anarchist heightening of native IWW militancy. He considered the CGT’s advocacy of industrial sabotage to “mark an epoch in the development of working class tactics,” founded on an understanding “that capitalist property is not sacred, but that it is simply stolen goods.” (Foster 12/8/1910)

At the same time, he criticized the views of some CGT members who considered sabotage “a general panacea for their social ills” and failed to see that violent tactics could enable state repression. (Barrett 45-6)

Foster aligned with Wobbly anti-politicals, arguing that adopting a “no politics in the union” rule was key to the CGT’s success. In his account, battles between socialist factions aiming to rule or ruin the CGT marked its early history. He argued that elected Socialists in France “persecuted (the CGT) with the most vigor,” and that Socialist railroad union leader Niel broke the 1909 strike led by syndicalists.

He recommended that the IWW adopt “strict official neutrality towards all political parties, and as individuals to vigorously combat the political action theory (of advancing workers’ interests).” (Foster 3/23/1911, 1, 4)

Boring from Within

These ideas were controversial but not new in the IWW. But soon Foster noticed that the CGT had not organized its own separate dual union. Instead it had “bored from within,” forming organized “militant minority” groups (noyaux) inside the established union organizations. Through the noyaux, they eventually took the unions over. (Foner vol. 4, 417)

The CGT wasn’t huge, but with 400,000 members and a revolutionary leadership (compared to 14,000 members in the IWW in 1913), Foster considered the CGT the most feared workers’ organization in the world. He pointed to Emil Vandervelde, top official of the Second International, who admitted that the CGT had achieved more in practical results than the much larger Socialist-allied unions in Germany.

CGT head Leon Jouhaux said to Foster “tell the IWW, when you return to America, to get into the labor movement.” Jouhaux spoke from experience. A few months before Foster went to France, British IWW militant Tom Mann visited the CGT. Returning to the UK, he dropped out of the tiny British IWW and founded the Industrial Syndicalist Education League (ISEL). (Barrett, 48) British unions, the world’s oldest, were seen as notoriously conservative by radicals. (Foster 1922)

British syndicalists did not enjoy the French luxury of helping build the unions from the ground up. They confronted an established union movement under conservative leadership — like the AFL. Yet during the Great Labor Unrest of 1910-1914, Mann and the ISEL were “at, or near, the center of many disputes.”

These included the Liverpool transport strike of 1911, whose strike committee Mann headed. This was “the most serious challenge to capitalist authority” because the “strike committee began to act as an alternative organ of class power through its control over the city’s transport system.” (Darlington, 85, 78)

The ISEL thus campaigned successfully for militant direct action. It also advanced demands for amalgamation of craft unions into industrial unions “of all workers on the basis of class.” The formation of the National Transport Workers’ Federation in 1910, the 1913 National Union of Railwaymen, and in 1914 the Triple Alliance of miners, railway workers, and transport workers followed. (Darlington, 65)

Foster marveled at these achievements, carried out by Mann and a few dozen followers entering the existing unions as an organized League. Following Jouhaux’s advice, Foster attended the 1911 IWW Convention and proposed that it focus on boring from within AFL unions in order to revolutionize them. He won over five out of 31 delegates, including Jack Johnstone of Vancouver BC and Earl Ford of Seattle.

Then he wrote an editorial for the Wobbly paper Industrial Worker, “Why won’t the IWW grow?” His answer: the founders’ “dogma” of dual unionism. (Foner vol. 4, 419) Foster later related IWW dual unionism to the alleged sectarian proclivities of its “socialist politician” founders Debs and DeLeon. (Foster and Ford, 32)

The way to “revolutionary unionism,” he wrote, was to “give up the attempt to create a new labor movement, turn (ourselves) into a propaganda league, get into the organized labor movement, and by building up better fighting machines within the old unions than those possessed by our reactionary enemies, revolutionize these unions even as our French Syndicalist fellow workers have so successfully done with theirs.” (Foner vol. 4, 420)

IWW papers Solidarity and Industrial Worker hosted a debate on Foster’s proposal. One Wobbly related successfully boring from within the Seattle AFL, complaining that success turned to failure when the borers abandoned the effort and joined the IWW instead.

Johnstone wrote that the “strongest weapon” of conservative “labor fakers” was to argue that radical dual unionists aimed to destroy their organizations.

But most letters opposed Foster. They called the AFL a “corpse” and job trust, said the United States was different from France because it had more unskilled workers, that many Wobblies had already been kicked out of AFL unions, and that most IWW members couldn’t join the skilled craft unions of the AFL.

Others argued that some IWW members, still inside AFL unions as “dual card holders,” were already “boring from within,” and that this complemented attempts to build dual unions outside. Solidarity declared “discussion closed” on December 16, 1911. (Foner vol. 4, 421)

Claiming he didn’t get to respond fully, Foster wrote a series of articles for the Washington Agitator, paper of anarchist Jay Fox. Foster argued that “dual card holders” could not successfully bore from within, because the workers’ correct instinct for unity made it easy for conservative leaders to attack them as rival unionists. Further, the AFL would prevent the growth of any radical rival by scabbing on its strikes.

To those who declared the AFL dead due to its outdated craft structure, he declared the form of organization less important than revolutionary spirit. In France and England even conservative unions had been revolutionized, and converted from craft to industrial unions. He pointed out that some mainstream U.S. unions were already moving toward industrial organization.

Organizing the unorganized, Foster claimed, would proceed far faster if militants captured AFL resources for the purpose — something his own efforts at the end of the decade would prove spectacularly. Most of all he hammered the message that dual unionism robbed the AFL of its natural “militant minority,” leaving the conservative “labor fakers” in charge. (Foner vol. 4, 422-36)

The Syndicalist League of North America

Now Foster struck out on his own. Setting up shop in Chicago, he joined the mainstream Brotherhood of Railway Carmen, paying his last IWW dues February 15, 1912. Working as a car inspector 12 hours a day, seven days per week, he kept up correspondence with contacts across the country. But first he had to jumpstart his own “militant minority” group.

Drawing on his hobo skills, he rode freight cars to towns across the country, speaking before IWW and AFL locals. On one brutal ride in March, Foster almost froze to death on the high plains. His speaking tour failed to pull IWW Branches away, but it did induce individuals and small groups to join him.

Foster wrote in the Agitator that the IWW failed because it tried to be both a propaganda society and a union federation. Instead a loose network linked together by a newspaper was needed. (Foner, Ibid.)

Foster convinced Jay Fox, a labor anarchist with roots in the Haymarket period and Debs’ American Railway Union, to relaunch his paper under joint editorship with him. They called it the Syndicalist. After an August 15, 1912 article calling “direct actionists” of the “militant minority” to contact him personally, a Chicago gathering formally launched the Syndicalist League of North America (SLNA) in September.

League members, mostly ex-Wobblies and worker anarchists, joined their local AFL unions. Branches formed in Nelson and Vancouver, British Columbia (BC Canada, where Johnstone worked), Kansas City, St. Louis, Omaha, Chicago, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, Tacoma, San Diego and Denver.

Reflecting Foster’s emphasis on avoiding even the appearance of dual unionism, the League had no membership fees. Income came only from donations and selling publications, while National Secretary Foster took no salary and kept his day job.

Foster wrote that the SLNA was “the first definite organization in the U.S. for boring from within the trade unions by revolutionaries.” It was “not a political party or a union. It would not organize unions except to assist and act as a recruiting ground for all unions. It was not pro-AFL and not anti-IWW, but mainly encouraged militants to enter the AFL.” Stressing a refreshing non-sectarianism absent from both the AFL and the IWW, he declared that it would support all workers’ struggles. (Foner vol. 4, 428-29)

The SLNA attracted worker revolutionaries who worked with Foster over the next decade and beyond. In the 1920s they made up much of the initial core of the U.S. Communist Party’s (CP) labor activists. Besides Johnstone and Fox, who brought their own contacts into the SLNA, the great Lucy Parsons joined the Chicago Branch and hosted meetings at her home.

Sam T. Hammersmark was another Haymarket veteran who later participated in the 1917 packinghouse campaign. Ironworker Joe Manley joined the League, Kansas City unionist and future CP Chairman Earl Browder collaborated closely with it, and so did James Cannon (though Cannon remained in the IWW). (Barrett, 62-63) Tom Mooney was yet another working-class luminary in the League. (Johanningsmeier 1989, 329-53)

The League scored major successes in Kansas City. Bringing vision and ambition to the City Trades’ Council, they helped it launch the “Labor Forward” campaign. They “led several important strikes” and “organized numerous AFL locals,” adding 10,000-15,000 new union members by 1916.

Browder led an auditing committee that uncovered corruption and helped drive out the conservative head of the Council. (Barrett, 63) Foster claimed that after that the League had “virtual” control of the Kansas City Council, and “practical control” of the Cooks, Barbers, and Office Workers’ unions. (Johanningsmeier 1994, 71)

In St. Louis, League members led strikes of waiters, taxi drivers, and telephone operators. Fox became Vice President of the International Union of Timberworkers, which organized a one-day general strike for the eight-hour day on May Day.

Foster claimed that the SLNA “practically controlled the AF of L” in Nelson, BC. The SLNA had about 2000 members at its height. (Barrett, 63, 58) Operating in a period of labor upturn, its accomplishments suggested some promise for the novel combination of boring from within the unions as a militant minority.

Never before in the United States had revolutionaries so self-consciously organized themselves precisely to maximize their contact and influence with the mass of workers, and to minimize all separation. They began transcending in practice the apparent contradiction in union work between revolutionary principles on the one hand, and mass action, connections, and influence, on the other.

But though it began a long and fruitful (if small) tradition, the group itself faded out by 1915. The SLNA “made quite a stir,” Foster later wrote, but it “was born before its time. The rebel elements generally were still too infatuated with dual unionism.”

This was especially so because the IWW in 1912 began to catch the wave of the broader labor upturn itself. It was the year of the famous Lawrence strike. “The IWW made a great show of vitality” and eclipsed the League, he wrote. (Foster 1922, “Bankruptcy”)

Also, as Foster himself later thought, “because of his belief in decentralization, the national league was incapable of developing into a very unified organization.” Finally, Foster later argued that the group’s “leftist direct attacks upon the workers’ nationalistic feelings and their religion also needlessly alienated the mass of workers” — an error he would zealously correct in his next venture. (Johanningsmeier 1994, 71, 78)

The ITUEL and “Right Opportunism”

Attempting to relaunch, Foster and 13 former SLNA members met January 7, 1915 in St. Louis and founded the International Trade Union Education League (ITUEL). Foster logged 7000 miles on yet another hobo trip, but at the end of it still had only the Chicago chapter. The fewer than 100 members there held key positions (for example as business agents and organizers) in the painters, machinists, carpenters, tailors, retail clerks, garment workers, and iron molders. (Barrett, 66-68)

Though stillborn, the new organization helped to bind the network of collaborators who would participate in big campaigns to come. (Johanningsmeier 1989) Foster also at this time produced a new pamphlet — Trade Unionism: The Road to Freedom. Ditching anarchist rhetoric for language closer to mainstream U.S. political traditions, he called for workers to “join the Trade Union Movement and be a fighter in the glorious cause of liberty!”

Unions, he argued, “by their very nature driven on to the revolutionary goal,” he wrote. “As their strength grew, organized labor would inevitably overthrow the wages system.” Even craft unions concerned only with partial demands were “as insatiable as the veriest so-called revolutionary union.” (Quoted in Johaninngsmeier 1994, 80, 81)

The SLNA’s successes had followed the French CGT model of an organized minority gaining influence inside unions. In their ITUEL and succeeding campaigns, the Foster coterie owed more to the British Industrial Syndicalist Education League’s stress on amalgamating craft unions. The direct-action emphasis on the strike weapon, plus appeals to rank and file militancy against union leaders, continued, as did Foster’s commitment to unions as revolutionary and anti-capitalist.

As the ITUEL faded out, its members still bored from within but no longer built a militant minority formation. So, facing conservatizing pressures as an individual, the stage was set for what Foster later called his “sag into right opportunism.” (Barrett, 66)

His worst “sag” was support for the United States in World War I. Foster saw the war as labor’s moment, in which domestic labor shortages in war production would increase unions’ leverage. He even spoke in war bond sales drives. (Murray, 448)

In the Big Leagues: The Packinghouse Campaign

Before the war Foster, as a delegate to the Chicago Federation of Labor, proposed to affiliate all 125,000 railroad industry workers into a citywide council federating the railroad craft unions. (Barrett, 69) With the U.S. entry into the war in April 1917, his sights rose. “‘One day as I was walking to work…it struck me suddenly that perhaps I could get a campaign started to organize the workers in the great Chicago packinghouses” (including the railroad workers servicing them). (Foster 1937, 91. Quoted in Foner vol. 7, 235)

Months later his brainstorm led to an achievement previously untried by the AFL — “the first (unionization of a) mass production industry in the United States.” (Foner vol. 7, 235) Foster believed “such a great influx of members…would lead to the revolutionization of the AF of L.” (Barrett, 78) To meet this challenge he sought a new non-segregated, actively anti-racist organizing strategy.

The defeat of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen (AMC) in the 1904 strike left only its organized “remnants…(among) the predominantly Irish and German ‘butcher aristocracy.’” (Halpern, 44) But struggle spontaneously revived in the packinghouses during the war.

A general labor shortage resulted from conscription and an 80% immigration dropoff. With workers in demand, meatpacking jobs lost out to less unpleasant employments. Annual labor turnover in the industry by 1917-18 stood at 334%. Aware of their newfound leverage, unskilled Polish, Slova, and Lithuanian workers struck individual departments “at a frenzied pace throughout 1916 and 1917.”

“Business cannot be conducted in an orderly manner in this age of unrest” said one executive. Stockyard worker Arthur Kampfert wrote of leading a pork-trimmers’ strike in 1916. Workers elected him to a bargaining committee which won a four cent per hour raise. The company then fired Kampfert. Within a month he led a walkout at the next plant, winning a five-cent increase in a three-hour strike. This sparked several other wildcats.

As in the Haymarket days, Chicago stood as a beacon for progressive labor, through the Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL). From 1917-19 it launched a Labor Party effort, worked with feminists to organize teachers, and led in the campaign to free framed unionist (and SLNA alum) Tom Mooney. (Halpern 45, 47-8, 50)

Led by Irish nationalist John Fitzpatrick, the CFL allowed space for Foster and other radicals to take initiatives. While neither a syndicalist nor revolutionary, Fitzpatrick advocated industrial unionism (Johanningsmeier 1994, 91)

Foster’s Railway Carmen endorsed his packinghouse plan July 11, 1917. Within a week the AMC and CFL followed. His innovation was forming the Stockyards Labor Council (SLC), with representatives from more than ten craft unions. These jealously guarded jurisdiction over different jobs. But the SLC — as in Tom Mann’s ISEL amalgamation schemes — ran the organizing drive. Foster and Johnstone got paid to lead it.

A Polish and a Lithuanian organizer (both of whom turned out to be company spies) came on board to reach the largest immigrant groups. (Foner vol. 7, 235-36) The AFL and United Mineworkers provided Black organizers. The Women’s Trade Union League assigned Irene Goins to recruit Black women. (Barrett, 79-80)

Necessary resources depended on a diverse coalition, and tensions flared between conservatives and radicals at every turning point. Foster considered AMC officials “reactionary,” while AMC President Dennis Lane complained of “self-elected” SLC leaders Foster and Johnstone “mak(ing) laws to suit themselves.” (Halpern, 55; Johanningsmeier 1994, 104)

Balancing agendas of the craft locals, pushing back on AFL conservatism, and above all fighting racist divisions among workers made an incredibly daunting task of organizing these workers “for years…considered unorganizable.” But by year’s end the President’s Mediation Commission estimated 25-50 percent of packinghouse workers had joined. (Foner vol. 7, 235, 236)

Foster spoke before “fraternal and other community groups.” The drive “caught fire…especially among Poles.” More than 20,000 Slavic workers signed up by war’s end, and white workers as a whole largely joined. (Barrett, 79)

“Black politicians and preachers…subsidized by the packers” opposed the SLC and promoted a Black-only company union, the American Unity Packers Union, which stated it did “not believe in strikes.” Worse, some national stockyard unions constitutionally forbade Black membership.

Foster fought these provisions, but ultimately had to accept a supposedly temporary Jim Crow compromise in which Samuel Gompers agreed to charter all-Black AFL “federal labor unions” to be part of the SLC. Black workers were promised they would later be transferred into “locals of their respective crafts.” Meanwhile, the federal labor unions excluded women. (Foner vol. 7, 237-38)

Most Black stockyard workers came during the wartime “Great Migration” from the South. Chicago was “the leading center of Black industrial labor during World War One.” In 1915 1100 Blacks worked in the packinghouses (5%); by 1918, 10,000 (20%). (Street 659, 660)

“Northern” Blacks, in Chicago prior to the War, joined the unions as much or more than European immigrants — to the tune of 90% by 1918. But a different set of experiences and pressures made the Southerners hesitant. Few other industries hired Blacks at all, and packers promoted Blacks somewhat more readily than elsewhere.

Forcibly concentrated into a ghetto “Black Belt” near the stockyards, and as yet lacking community support structures Poles and others had built over years, new Black workers depended more on the goodwill of their bosses to survive. (Street 667, 663-64) As Foster said, “The colored man as a blood race has been oppressed for hundreds of years. The white man has enslaved him, and they don’t feel confidence in the trade unions.” (Johanningsmeier 1994, 108)

Racist condescension or outright hatred from white workers could be confronted by unions, or manipulated by packers. Since they couldn’t shut down production if Blacks and supervisors worked through strikes, union leverage depended on solidarity over racism. Packer Philip Armour admitted to “keep(ing) the races and nationalities apart after working hours, and to foment(ing) suspicion, rivalry, and even enmity among such groups.”

Inside the plants, the Wilson company transferred loyal Black workers from its southern plants to fight the union on the shop floor. Austin “Heavy” Williams, beef kill boss at Wilson, used favoritism in job assignments against pro-union Blacks, “preached against the union,” and “backed up his beliefs with his powerful fists.” He was part of a group of 15 southern Blacks working against the union. Meanwhile on the same killing floor, Black unionists Frank Custer and Robert Bedford braved abuse, scorn from fellow Blacks, and discrimination from the company to act as one-half of the stewards’ team representing Black and white workers together. (Halpern 24, 64, 57-8)

Recognizing that “organizing the colored worker was the real problem,” Foster “aggressively pursued African-American grievances, including racial discrimination.” He spoke before Black community groups, and cultivated a group of active Black worker militants for the campaign. (The SLC also demanded equal pay for women). (Barrett. 80; Foner vol. 7, 238)

Through these efforts the SLC made headway toward Black-white unity. Historian Paul Street claims the SLC “probably never recruited more than 20 percent of Chicago’s Black packinghouse workers,” but James Barrett estimates that 4,000-5,000 Black workers joined, while Philip Foner says “estimates vary between 6,000 and 10,000.” (Street, 662; Barrett, 80; Foner, vol. 7, 237)

Workers pushed to strike in late 1917. Samuel Gompers and the AMC opposed, but Foster organized a membership strike vote, which came out massively in favor. (Halpern, 54; Barrett, 81) The strike threat forced the White House to mediate to avoid disruption in war provisions. At the ensuing public hearings, Fitzpatrick said that the unions “will be unable to prevent a walkout if the (mediator’s) decision is not announced immediately.”

Federal Judge Samuel B. Altschuler then produced a March 30, 1918 ruling granting, in Foster’s words, “85% of the union’s demands.” While not gaining union recognition, workers won an 8-hour day, overtime pay, a 20-minute paid lunch period, a 10% wage increase, seniority rights, and clean dressing areas and bathrooms. The judgment banned racial discrimination in hiring and work assignments. (Foner vol. 7, 236)

Aftermath of the Victory

The impressive settlement boosted membership. The largest SLC affiliate, the AMC, claimed 62,857 members in November 1918, ten times more than in 1916. (Barrett, 82; Foner vol.7, 237)

But that month the war ended. Returning workers flooded home. Unemployment soared, with Black workers hit hardest — in May 1919 “10,000 Black laborers were searching for work.” As racial tensions rose, “fist fights broke out regularly” in the stockyards, “and frequently these altercations escalated into brawls involving bricks, knives, and even guns.” Menacingly, May and June saw race riots in Texas, South Carolina, and Washington DC. (Halpern, 62)

The SLC responded in a “‘giant stockyards celebration’” of solidarity, with an interracial parade through Black and white neighborhoods. The packers disingenuously claimed the march would cause racial conflict, and the City banned it. The SLC had two separate marches which joined together at the end. The CFL claimed 30,000 marched.

“One placard declared: ‘The bosses think that because we are of different color and different nationalities that we should fight each other. We are going to fool them and fight for a common cause — a square deal for all.’”

The “buoyant mood” after the march led to “concrete organizational gains among the previously aloof Black workforce.” The companies stepped up harassment, leading to a strike of 10,000 successfully demanding removal of the packers’ goons.

But on July 27, after Blacks went to a “whites only” beach, the Chicago Race Riot began. In five days it left 23 Blacks and 15 whites killed, and burned hundreds of homes.

Democratic Alderman Frank Ragen sponsored an “athletic club” — Ragen’s Colts — operating as an Irish street gang. They attacked Blacks with impunity. An official investigation found that without such gangs, “‘it is doubtful if the riot would have gone beyond the first clash.”

White immigrant workers in the packinghouse “Back of the Yards” District “interceded to protect Blacks from pursuing mobs.” The pro-labor Polish language press even published an anti-racist historical article asking of Blacks “Is it not right they should hate whites?” (Halpern 65, 66-7)

But these real beginnings of interracial solidarity lacked the momentum to overcome the tide of mistrust. This decisively affected stockyards workers. Now the craft unions either failed to honor the promise to incorporate Blacks, or to admit them on equal terms. (Foner vol. 7, 238)

The SLC had never won a contract. Without one the packinghouses used high unemployment, racial and craft-union divisions, and the repressive post-War political environment to break the union.

The packinghouse campaign showed the obstacles between the conservative, racist and petty-craft structured unions, and the goal of industrial organization. When the CIO’s Packinghouse Workers’ Organizing Committee finally unionized the yards in the 1930s, they used a simple all-embracing industrial charter. But in other ways they followed the SLC.

Foster’s packinghouse tactics centrally emphasized anti-racism, foreshadowing the best of the CIO. The Depression-era Communist Party, in one sense a larger, tighter version of a “militant minority” group, went further.

CP militants worked for active anti-racist and class struggle on a multiracial basis, citywide — organizing against evictions, for example — as well as in the packinghouses. Inside, their members patiently re-unionized at the shop-floor level. (Halpern, 102) With organized Black Communist rank-and-filers as the vanguard, this combination would finally prove strong enough for unionization to win over racial division.

High on temporary success in the stockyards, in April 1918 Foster hatched an even more ambitious plan. (Foner vol. 8, 151) He would seek CFL backing for a nationwide steel organizing drive. Then he could bid for national AFL support. If successful, this drive would swell the AFL with unskilled immigrants in the country’s key heavy industry. Transformed bottom to top, Foster dreamed, the AFL could then launch similar drives across the full range of U.S. mass production industries. (Barrett, 84)

On to Steel

The steel campaign paralleled packinghouse in several ways. Steel too saw wartime labor shortages partially filled by migrating Black southerners. Indiana’s Black steel work force rose to 14.2% by 1918. (Brody, 46)

Immigrant workers fought wartime price and production pressures in unofficial strikes. On January 7, 1916 Youngstown Sheet and Tube security guards fired on striking workers, igniting rioting that burned four city blocks. Pittsburgh stood on the edge of a general strike in April when steelworkers joined Westinghouse factory hands in striking and rioting for the eight-hour day.

AFL craft unions in the mills capitalized on this unrest. The Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel, and Tin Workers, for example, went from 7,000 to 19,000 members from 1915 to 1918. (Brody 47, 49) The CFL jumped on board Foster’s proposed steel campaign, and the reviving Amalgamated Association gave “at least lukewarm support.”

Foster and Fitzpatrick then organized three meetings on steel organizing at the June 1918 AFL Convention. On their request the AFL set up the National Committee for Organizing Iron and Steel Workers August 1. Like the SLC, the 24 federated unions in the National Committee agreed on paper to pool resources and follow the Committee. (Foner vol. 8, 151-52)

Gompers as AFL president nominally headed the Committee. But Fitzpatrick and Secretary-Treasurer Foster led the actual work. Iron and steelworkers’ councils brought together the different unions in each city. Foster said “these knit the movement together…strengthened the weaker unions…prevented irresponsible strike action by over-zealous single trades…[and] inculcated the indispensable conception of solidarity along industrial lines.”

The National Committee had little formal authority: “This is a federated proposition, and it is a free-will organization,” he said. In fact, “Chairman Fitzpatrick never knew how many organizers were in the field,” because each union kept control of its own employees.

But as in the SLC, vision and initiative empowered the radicals. William Hannon, Machinists’ representative on the Committee, commented that “the Secretary (Foster) of the National Committee assumed the leadership, the International representatives having but little to say about (the strike’s) direction.” (Brody 66-7, 165)

Foster requested $500,000 from the 24 unions to launch a “hurricane drive simultaneously in all steel centers.” (Foner vol. 8, 152) But at the first meeting they pledged a pathetic $100 each, and only “one or more” organizers per union. By year’s end they had contributed $6,322.50 in total. Starting in January they agreed to increase this to $5,000 per month, but they consistently failed to meet this.

Instead of Foster’s organizing hurricane, the Committee had to settle for a launch in the key centers of Gary and Pittsburgh. Wretched financial backing was, in historian David Brody’s judgment, “The Committee’s first major failure, and, in retrospect, probably the fatal one.” (Brody 68-9; Foner vol. 8, 152)

Immigrant workers in Gary joined the Committee through mass meetings there. Foster said their response “compared favorably with that shown in any organized effort ever put forth by workingmen on this continent.” One organizer complained that the native born showed much greater restraint. But they came on board once immigrants led the way. Success in the Chicago District, which included Gary, gave momentum to expand the drive to Ohio, Pennsylvania and Colorado.

But the end of the war on November 11 changed the balance of power. The National War Labor Board had mandated shop committees to handle grievances in steel as a means of preventing strikes. Bethlehem Steel President Eugene Grace informed a Board functionary on November 17 that the company would no longer comply with his orders. (Brody 75, 76)

With war production ended, government pressure eased, and unemployment rising, the companies now made war on the workers. In February 1919 Midvale Steel fired “hundreds of men…point blank.” “They are picking out and discharging the oldest employees they have who belong to unions…Many of the men have from 10 to 35 years in point of service.” (Foster quoted in Brody, 87)

Workers in dozens of steel company towns, with judges and police loyal to the mill owners, faced constant spying, harassment, and bans on freedom of assembly. Foster responded with a page from the IWW playbook — free speech campaigns across the steel-making Monongahela Valley. (Foner vol. 8, 154; Barrett, 89)

In Monessen, PA, the Committee defied an ordinance to organize a mass meeting on April 1. Thousands of union miners from surrounding country marched into town in solidarity, leading officials to back off threats of prosecution. Monessen became a union stronghold. (Brody 92-93) Legendary radical Mother Jones, 89 years old, broke a free speech ban in Homestead PA, went to jail, and was quickly released “to dissuade an angry crowd bent on freeing her.” (Foner vol. 8, 154-56)

Fourteen workers died before the Great Steel Strike started. (Barrett, 91) Fannie Sellins, on loan to the National Committee from the Mineworkers, died at the hands of Allegheny County cops. She had successfully organized three US Steel plants. But workers had begun to lose their fear. The repression pushed immigrant workers to break with their conservative community leaders and join the fight. Postwar layoffs also fueled rage. One hundred thousand workers joined by June. Local workers demanded a six-hour day, a demand not envisaged by Foster or the National Committee. (Foner vol. 8, 154-56)

The Historic Steel Strike

Pressure to strike built, especially as Elbert Gary of U.S. Steel openly organized intransigence against union recognition across the industry. When Gompers equivocated, Foster again leaned on the ranks, organizing a rank and file National Conference and strike vote. On August 20, 98% voted to grant strike authority to the National Committee, should negotiations fail. (Barrett, 89-90)

Elbert Gary refused any meeting when Foster and Fitzpatrick called on him August 26. Gompers then set up a meeting with President Woodrow Wilson on August 29. Wilson promised to strong-arm Gary into negotiations. According to Gompers, Wilson said “the time had passed when any man should refuse to meet with the representatives of his employees.”

The Administration did pass Wilson’s request to Gary. But when Gary refused, they did not tell the public. On September 10 the Committee set a strike date for September 22. (Brody, 101-05)

With shock they learned from the news that Wilson demanded the unions hold off striking. He organized an October 6 Industrial Conference of labor, management and the public, to discuss postwar production. While the Committee had hoped Wilson would help them in the battle for public opinion, by communicating secretly with Gary and publicly with them he had done the opposite.

Gompers and seven union presidents on the National Committee pushed for compliance with Wilson. Meanwhile telegrams from the local steelworkers’ councils warned “the men will strike regardless.” (Brody, 105-06) Foster, Fitzpatrick and the Committee majority overcame Gompers, arguing that delay would fatally demoralize the surging masses. (Barrett, 89-90)

The National Committee claimed that 275,000 workers struck the first day, growing to 365,000 next week. Historian David Brody, citing production figures, says “the actual number was probably somewhere around 250,000 — about half the industry’s work force.” But he notes it “still exceeded in magnitude and scope anything in the nation’s experience,” and “proved once and for all that a national strike could be mounted against a basic industry.” (Foner vol. 8, 160; Brody, 113-14)

The strike spanned Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Colorado. But the “unexpectedly strong” movement soon succumbed to long odds. The race divide proved crucial again, as employers imported Black and Mexican strikebreakers from points south. (Foner vol. 8, 160-65)

Gary’s heartlessness “had aroused considerable animosity,” and the steel companies saw the initial “basic sympathy” of the public for the strike. They “began a concerted drive” to make Bolshevism the issue. Politicians and the media slandered the workforce as un-American radicals, singling out Foster’s old Syndicalism pamphlet. U.S. flags at strike headquarters failed to prevent this. Heralding the anti-labor reaction of the 1920s, police violence and free-speech bans returned with a vengeance. (Murray 452-53; Foner vol. 8, 160-66)

The Feds got involved too. The Department of Justice’s Palmer raids expanded to steel towns, and “hundreds of steelworkers were detained, most of them aliens who could be deported.”

The New York Times reported a false story of a gun battle between state police and Wobblies/Bolsheviks in Sharon, PA. But it was the true story of a Gary, Indiana riot pitting strikers against imported Black strikebreakers on October 4 that brought in Federal troops. General Leonard Wood, angling for a Presidential run, occupied steelworkers’ citadel Gary. He organized a hysterical round-up of “caches of weapons, secret societies…(and) foreigners professing a belief in violence and revolution.” (Brody, 134-35)

Momentum slipping, the Amalgamated Association broke ranks. More than half of the recruits to the National Committee fell under the Association’s jurisdiction, increasing their revenue far more than their contributions to the strike fund.

Worse, some 5000 skilled workers in independent finishing mills had contracts owned by the craft union. When these workers struck (along with new, unskilled Association members not covered by the existing contracts), Association President Michael Tighe ordered them back to work.

The Cleveland local refused, so Tighe revoked their charter. Fitzpatrick asked whether “the contractual obligation to employers was more sacred than the moral obligation to the other unions” — but the answer, for Tighe, was yes. (Brody, 167-68)

The beaten down strike was called off January 8. Though a few left-inclined unions — ILGWU, Furriers and ACTWU — had contributed generously to the strike fund, the overall picture was severe neglect. The 24 unions in the Committee provided only $46,000 of their pledged $100,000. (Foner vol. 8, 166)

As Foster wrote, “Mr. Gompers sabotaged the steel strike from beginning to end.” (Foster 1922) In his book about the strike, he argued that the resources committed “represented only a fraction of the power the unions should and could have thrown into the fight. The organization of the steel industry should hav e been a special order of business for the whole labor movement. But…the big men of labor could not be sufficiently awakened.” (Foster 1971, 234-35 )

Foster also blamed racist discriminatory practices by the unions, arguing “nothing short of…(their abolition) will achieve the desired result. (Foster 1920, 209-10; quoted in Foner vol. 8, 168) Reflecting on the wartime era of tight labor markets, he wrote that “even with a mediocre organizer, instead of a ‘labor statesman’…(heading the AFL), great armies of toilers could have been drawn into the labor organizations.” (Foster 1922) Foster and his crew of revolutionary unionists, who joined him in the steelworkers’ campaign, had shown this to the world.

Conclusion

Even during his self-described “right opportunist” phase, Foster’s work contributed to the revolutionary labor tradition. It proved on a grand scale that anti-racism, industrial organization, militancy and democracy could be advanced from inside conservative-bureaucratic unions, growing and transforming them in the process.

Foster appreciated the flexibility of unions, which he described as “afflicted by all sorts of capitalist ideas…because the workers as a whole suffer from them.” (Foster 1922) But though sharply critical he never fully theorized the union bureaucracy, later understood as an intermediate social layer with its own conservatizing material stake in labor stability, but wavering between the shifting class pressures of the capitalists above them and the workers below.

Accepting union staff positions removing him from the rank and file, Foster’s somewhat individualist practice in this period partly anticipated the unprincipled and ultimately barren late 1930s Communist Party practice of “permeationism.” This meant ostensibly trying to revolutionize unions by seeking union office independent of active rank and file mandates, often while hiding one’s affiliations. (On this history see Moody 2014)

Still boring from within, Foster had temporarily abandoned the other of his two guiding concepts — that of the organized militant minority. Though he often gave that notion an unnecessary elitist bent,(2) it had been key to revolutionary union work. Accountable in some way to a formal collective in the SLNA, the conservative pulls on “borers from within” the unions had met a sturdier counterbalance than their individual wills.

Yet profoundly enriched by his wartime experiences in the big leagues of labor and politics, Foster would return to organize a bigger and better militant minority formation in the years ahead. This was part of the international Marxist-syndicalist synthesis of the early Communist International.

That story of the Trade Union Educational League, which directly inspired influential 1970s rank-and-file union caucuses, will be the subject of a future article.

Notes

- Barrett, 41. After the IWW settled, the free-speech fight continued under the leadership of AFL unions. Foster noted that this second phase of the struggle was more successful than the first. See Johanningsmeier 1994, 41-2.

back to text - For example, in Syndicalism, he wrote of the “weak and timid majority” of the working class (17), and that the militant minority “are the directing forces…the sluggish mass simply following their lead” owing to the minority’s “superior intellect, energy, courage, cunning, organizing ability, oratorical power, as the case may be.” (43-44) Later, in his early Communist period, he reflected these attitudes as follows: “revolutions are not brought about by…far-sighted revolutionaries…but by stupid masses who are goaded to desperate revolt…and who are led by straight-thinking revolutionaries.” (Barret, 122)

back to text

References

James R. Barrett, William Z Foster and the Tragedy of American Radicalism (University of Chicago Press, Urbana and Chicago, 1999).

Irving Bernstein, The Lean Years: A History of the American Worker 1920-1933 (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2010).

David Brody, Labor in Crisis: the Steel Strike of 1919 (University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 1987).

James P. Cannon, “The IWW — the Great Anticipation,” The First 10 Years of American Communism (Pathfinder Press, New York, 1962).

Ralph Darlington, Radical Unionism: the Rise and Fall of Revolutionary Syndicalism (Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2013).

Eugene V. Debs, “Speech at the founding of the IWW,” June 29, 1905, WWW Virtual Library, http://www.vlib.us/amdocs/texts/debs1905.html.

Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 1: From Colonial Times to the Founding of the American Federation of Labor (New York: International Publishers, 1962. Vol. 4: The Industrial Workers of the World (International Publishers, New York, 1965). Vol. 8: Postwar Struggles, 1918-1920 (International Publishers, New York, 1988).

William Z. Foster, “Spokane Fight for Free Speech Settled,” Industrial Worker (Seattle), vol. 1, no. 51 (3/12/1910), 1.

William Z. Foster, “Special News from France,” Industrial Worker (Spokane, WA), Vol. 2, no. 38 (12/8/1910).

William Z. Foster, “The Socialist and Syndicalist Movements in France,” Industrial Worker, vol. 3, no. 1, whole 105 (3/23/1911), 1, 4.

William Z. Foster, The Great Steel Strike and its Lessons (New York, 1920), 209-10. (Quoted in Foner, Vol. 8, 168.)

William Z. Foster, “The Bankruptcy of the American Labor Movement,” Labor Herald Library No. 4, 1922.

William Z. Foster, From Bryan to Stalin (New York, 1937), 91. Quoted in Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol, 7: Labor and World War I, 1914-1918 (International Publishers, New York, 1987), 235.

William Z. Foster, American Trade Unionism: Principles, Organization, Strategy, Tactics. Selected Writings (New York: International Publishers, 1970), 13, 12.

William Z. Foster, The Great Steel Strike and its Lessons (Da Capo Press, New York, 1971).

William Z. Foster and Earl C. Ford, Syndicalism (William Z Foster, Chicago, 1913).

Rick Halpern, Down on the Killing Floor: Black and White Workers in Chicago’s Packinghouses, 1904-54 (University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 1997).

Edward P. Johanningsmeier, Forging American Communism: The Life of William Z. Foster (Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press, 1994).

Edward P. Johanningsmeier, “William Z. Foster and the Syndicalist League of North America,” Labor History 30:3 (1989), 329–53.

Ira Kipnis, The American Socialist Movement, 1897-1912 (Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2004), 13.

David Montgomery, Workers’ Control in America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979), chapter 4, “The ‘New Unionism’ and the transformation of workers’ consciousness in America, 1909-22.”

Kim Moody, “The Rank and File Strategy,” in In Solidarity: Essays on Working-Class Organizations and Strategy in the United States (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2014).

Robert K. Murray, “Communism and the Great Steel Strike of 1919,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol, 38, No. 3 (December 1951).

Preamble to IWW Constitution, https://www.iww.org/culture/official/preamble.shtml.

Vincent St. John, “The IWW — Its History, Structure, and Methods, ”http://www.library.arizona.edu/exhibits/bisbee/docs/019.html.

Paul Street, “The Logic and Limits of ‘Plant Loyalty’: Black Workers, White Labor, and Corporate Racial Paternalism in Chicago’s Stockyards, 1916-1940,” Journal of Social History, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Spring 1996), 659.

Leo Wolman, “Union Membership in Great Britain and the United States,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Bulletin 68, December 27, 1937, 2, http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5410.pdf.

November-December 2019, ATC 203