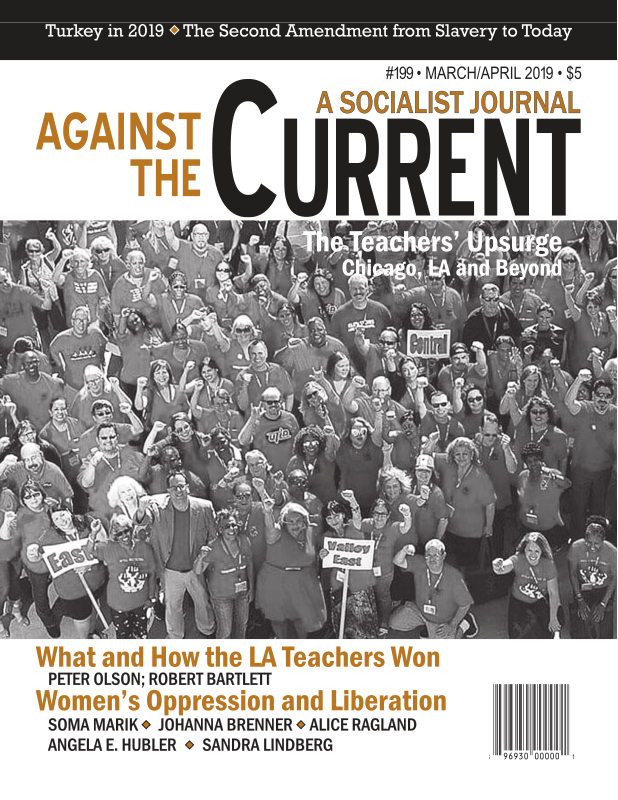

Against the Current, No. 199, March/April 2019

-

Whose "Security" -- and for What?

— The Editors -

MLK in Memphis, 1968

— Malik Miah -

California Burning, PG&E Bankrupt

— Barri Boone -

PG&E Bankruptcy

— Barri Boone -

What Los Angeles Teachers Won

— Peter Olson -

The UTLA Victory in Context

— Robert Bartlett -

Chicago Charter Teachers Strike, Win

— Robert Bartlett -

Turkey in 2019: An Assessment

— Yaşar Boran -

Betraying the Kurds

— David Finkel -

The Strange Career of the Second Amendment, Part II

— Jennifer Jopp -

Who Is Responsible?

— David Finkel -

A Note of Thanks

— The Editors - Socialist Feminism Today

-

Women's Oppression and Liberation

— Soma Marik -

Marx for Today: A Socialist-Feminist Reading

— Johanna Brenner -

Angela Davis: Relevant as Ever After Thirty Years

— Alice Ragland -

The Activism of Angela Davis

— David Finkel -

White Women and White Power

— Angela E. Hubler -

Lots of Scurrying But No Revolution in Sight

— Sandra Lindberg - Reviews

-

A Call to Action

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Orbán: Strong Man, Authoritarian Ideology

— Victor Nehéz -

A Sympathetic Critical Study

— Peter Solenberger -

Further Reading on the Russian Revolution

— Peter Solenberger

Patrick M. Quinn

We Can Do Better:

Ideas for Changing Society

By David Camfield

Halifax and Winnipeg, Canada; Fernwood Publishing, 2017, 168 pages, $25 paperback.

DAVID CAMFIELD’s WE Can Do Better represents a significant contribution to the literature of the Left. A Canadian academic and activist, Camfield has written an eminently readable and accessible book aimed at a broad readership.

While relatively short, its 132 pages of text are packed with historical, sociological, psychological, economic, political and cultural analysis. What Camfield sets out to do in this book is a tall order indeed, but he accomplishes it well.

The author provides an overview of contemporary society, primarily Canada, the United States and Britain, an analysis of the evolution of human society over the course of millennia, and a projection of what needs to be done to challenge and positively transform the prevailing capitalist social, political and economic order.

Camfield takes up the central question of “what is to be done” to positively transform society, situating this critical discussion in the context of his analysis of how human society has changed over centuries.

Camfield calls the method that he uses to analyze what happened in the past as well as contemporary society “reconstructed historical materialism.”

I find this a rather curious terminology — far better had he called his analytical method “updated and expanded historical materialism” since the method that he employs is neither new nor “reconstructed.”

The method of historical materialism was developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the mid-19th Century and extended by Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, among others, during the last decades of the 19th and early decades of the 20th centuries.

Marx and Engels drew upon the work of the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel in formulating their theory of historical materialism. Engels used the analytical method of historical materialism in writing his 1844 book, The Condition of the Working Class in England and in The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State.

Karl Marx used historical materialism in all his historical and political writing. It was the method employed by Lenin in his State and Revolution and What Is To Be Done? and by Leon Trotsky in his superb History of the Russian Revolution.

Camfield has updated and expanded the theory of historical materialism, as the publisher’s website puts it to “fuse critical Marxism with insights from anti-racist queer feminism” — concepts rarely addressed by the classic Marxist thinkers.

Rebuilding the Left

We Can Do Better contributes to the current discussion on the left about what needs to be done in order to rebuild socialism in the 21st century.

The global left during the period 1917 to 1990 was largely conditioned by the Russian Revolution of 1917. That period, for better and worse, came to a close in 1989-1990 with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the decline of the Soviet Union.

Largely because of the events of 1989-1990, the global left has been in a precipitous decline since then. Today it is weaker than it has been since before Marx and Engels put pen to paper to write The Communist Manifesto in 1848, amidst the momentous but ultimately defeated European revolutions of that year.

The best way to approach Camfield’s book might be to first read its introduction “About This Book,” its conclusion (Chapter 15), its glossary which follows the main text, its notes, his suggestions for further reading, his references and the book’s table of contents.

The table of contents reflects the book’s structure and how Camfield uses each chapter to build upon previous ones. The book is divided into four parts: Part I, titled “Popular but Defective: Three Schools of Theory;” Part II, “An Alternative: Reconstructed Historical Materialism;” Part III, “Answering Some of Today’s Questions,” and Part IV, “The Point Is To Change It.”

In Part I, Camfield recounts three theories advanced by defenders of the prevailing organization of contemporary society — Idealism, Evolutionary Psychology, and Neo-liberalism — and effectively refutes them.

Part II explains historical materialism, and uses it to analyze past societies and how societies change and evolve over time. In Chapter 7, perhaps the book’s most important chapter, Camfield dissects the prevailing capitalist mode of production, assesses its strengths and weaknesses, illustrates how patriarchy and racism are integral components of contemporary capitalism, and analyzes its present neoliberal form.

In Part III, he poses and answers a number of critical questions: whether today’s capitalism is making life better for most working people; why so little is being done about the dangers of climate change; why women are still oppressed by sexism; why racism is an integral component of contemporary capitalism; and perhaps most importantly, why there is so little “fight back” against the ravages of contemporary capitalism.

In Part IV, Camfield asks whether change for the better is possible and whether there is a better organization of society than capitalism. Answering both questions in the affirmative, he then proposes a rudimentary strategy for change, predicated upon involving larger and larger numbers of people in struggle against the capitalist system that oppresses them.

What’s Orthodox?

One might wish that Camfield had chosen a title that more adequately conveys what he is writing about. And one might wish that he had drawn upon the work of others who have preceded him, particularly the contributions of the Belgian Marxist and social and economic theorist, Ernest Mandel.

While Camfield criticizes “orthodox Marxism,” he does not elaborate what he means by it. And while he briefly discusses the rightward drift in the United States accelerated by President Donald Trump, his book would have benefited from a greater consideration of the role that racism plays in consolidating the white base of Trump’s supporters.

Perhaps a minor quibble: I do not agree with his characterization of the system prevalent in the former Soviet Union and its eastern European satellites as “state capitalism” — for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that such a characterization in effect downplays the perniciousness of “real” capitalism in which today an elite 1% of the population appropriates the surplus value created by the labor of the subordinate 99% and completely dominates society.

These caveats aside, We Can Do Better is a highly relevant contribution which will hopefully prompt further discussion and help build broad struggles against the capitalist system — struggles that will eventually grow into an offensive with the potential to replace it with a democratic, egalitarian system to the benefit of all humanity.

March-April 2019, ATC 199