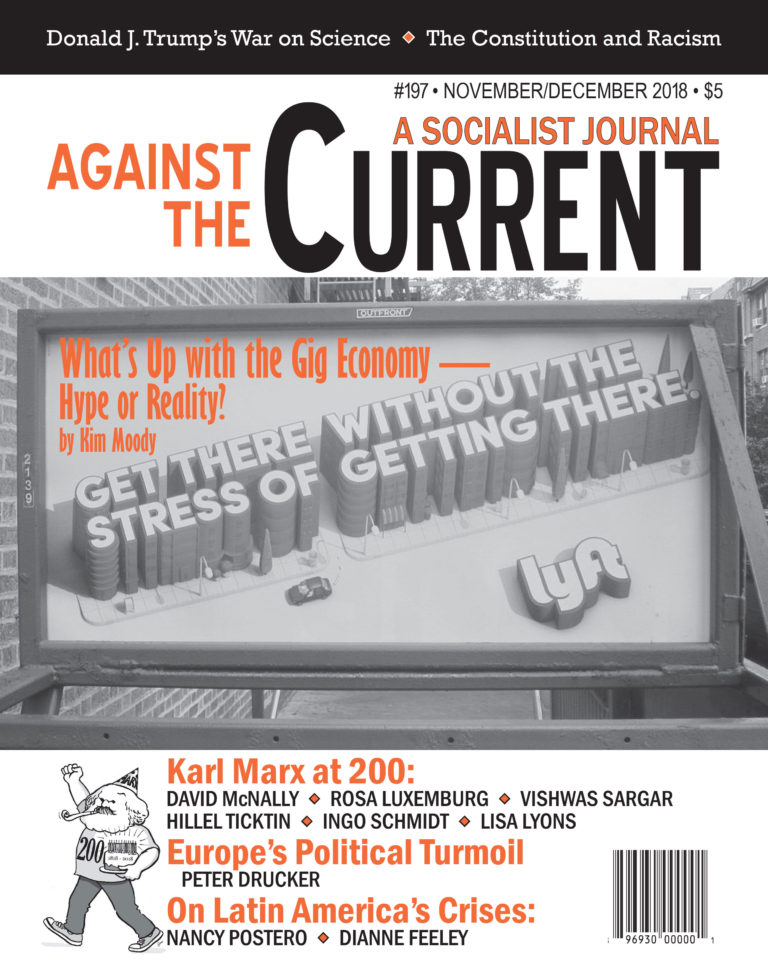

Against the Current, No. 197, November/December 2018

-

Supreme Toxicity -- Confirmed

— The Editors -

The Constitutional Root of Racism

— Malik Miah -

Trump and Science

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

Europe's Political Turmoil (Part I)

— Peter Drucker -

Ecosocialism or Climate Death

— Ecology Commision of the Fourth International - Realities of Labor

-

Is There a Gig Economy?

— Kim Moody - Karl Marx at 200

-

Karl Marx: Revolutionary Heretic

— David McNally -

Marxist Theory and the Proletariat

— Rosa Luxemburg -

Marx and the "International"

— Vishwas Satgar -

Karl Marx in the 21st Century

— Hillel Ticktin -

Marx's Capital as Organizing Tool

— Ingo Schmidt - A Century Ago

-

The End of "The Great War"

— Allen Ruff -

Triumph and Tragedy

— William Smaldone - Reviews

-

The Making of Corporate Empire

— Jane Slaughter -

The Saga of a City Rising

— Michael J. Friedman -

Slavery and Capitalism

— Dick J. Reavis -

The Logic of Human Survival

— Barry Sheppard -

Architects of Mass Slaughter

— Malik Miah -

Two Powerful Films on Indonesian Mass Terror

— Malik Miah -

The Wars of Rich Resources

— Nancy Postero -

Latin America Crises and Contradictions

— Dianne Feeley - In Memoriam

-

Jan and Carrol Cox, Political Activists

— Corey Mattison

William Smaldone

October Song:

Bolshevik Triumph, Communist Tragedy, 1917-1924

By Paul Le Blanc

Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017, 504 pages, $27.95 paperback.

THE HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY of the Bolshevik Revolution has generated a flood of new books on an event that shaped the global history of the 20th century and continues to reverberate today. Among these works, Paul Le Blanc’s October Song will surely endure as one most worth reading.

Over the course of his long career as a scholar and activist, Le Blanc has written at least 20 books on the history of the labor movement in Russia, Germany, and the United States and has focused extensively on Lenin and Bolshevism. This study brings his knowledge and excellent writing skills to bear in a wide-ranging analysis of the complex factors that transformed the inspiring Bolshevik triumph of 1917 into the Communist tragedy that culminated with Stalin.

Le Blanc’s sympathies with the Bolshevik project are clear, but this is no apologia. On the contrary, grounded in material and intellectual evidence, it is a work that helps us better understand the factors that shaped the choices the revolutionary leaders made and the alternatives paths that might have been open to them.

Le Blanc is particularly good at discussing debates among historians about a wide variety of issues in understandable and clear language. His book is not based on archival or Russian language sources. It is primarily a work of synthesis resting on materials available in English. It aims to present revolutionary Russia’s “objective realities” along with “a sense of the ‘subjective’ mixture of personalities, hopes, ideas, and experiences of people actually involved” in the revolutionary struggle, and concerns itself particularly with the problem of democracy — rule by the people — in the revolutionary process.

Le Blanc is quite successful in achieving these goals. Having mastered the English language literature, he draws on the most up-to-date information to describe the condition of late imperial and of revolutionary Russia, and makes excellent use of biographical and autobiographical works dealing with the top leaders of the various Russian political parties as well as lesser known leaders and rank-and-file workers.

Revolutionary Roots and Limitations

The basic argument of October Song is that the Bolshevik Party was a force “animated by radical democratic aspirations and dynamics.” Well rooted in the urban working class, it most accurately gave expression to the desires of Russia’s proletariat in the face of the imperial regime’s military, economic, and political collapse.

Following the February 1917 fall of the Tsar, the Bolsheviks became the primary opponents of the new Provisional Government — which, unwilling to end the war or carry out immediate elections for a national constituent assembly and unable to improve deteriorating living standards, became increasingly unpopular.

Unlike their rivals such as the Mensheviks, the Bolsheviks were willing to act and, based on strong urban support, to seize power. However, their ability to follow through with the democratic transformation of the country then was hindered by four serious limitations:

1) A failure to fully anticipate how overwhelming and violent would be the difficulties and hostile forces with which they were forced to contend.

2) A blind spot regarding the dangers of authoritarian “expedients” in dealing with such difficulties and hostile forces.

3) A failure to anticipate the potential of bureaucratic degeneration arising from within their own movement.

4) A problematic understanding of Russia’s peasant majority that would undermine the democratic and revolutionary orientation that had historically been central to their movement. (xiii)

Le Blanc highlights the interplay of these “internal limitations” with foreign military interventions and an economic blockade, which fueled the civil war and attempted to strangle the revolution; with the aftereffects of World War I and Bolshevik inexperience, which combined to devastate the economy; and with international isolation, resulting from the failure of the revolution to spread to the advanced capitalist countries. All these transformed the revolution from a radical-democratic into an authoritarian one.

None of these arguments are new, but Le Blanc, leaning heavily on Trotsky’s approach centering on the revolution’s bureaucratic degeneration, also draws on a wide array of other perspectives and combines them in a balanced and largely convincing way.

The author organizes his discussion into ten chapters tracing the history of the revolution from its origins in the late imperial period though the Bolsheviks’ seizure of power, their efforts to create a “mixed economy” in the early period of proletarian rule, the emergence of “war communism” in the context of civil war and the failure of the revolution to spread, and finally the consolidation of the Soviet Republic under the “New Economic Policy (NEP).”

As this chronology unfolds, he focuses on particular themes such as how the revolution “lost its balance” and turned toward authoritarianism and the meaning of “liberty” under the Soviets. He closes with an analysis of the extent to which the outcome of the revolution was “inevitable” and with an interesting appendix on methodology.

Russia’s Development and Politics

Although well written, this is not a book for readers with little knowledge of the basic events. Le Blanc’s focus on major theoretical and political themes sometimes leads him to give short shrift to some of the revolution’s important moments.

Le Blanc’s analysis of pre-revolutionary Russia concentrates on the rapid development of capitalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and its impact on the empire’s class structure and political system. As have many other historians, the author recognizes that Russia’s economic and social development differed markedly from that of the more advanced capitalist states in Western Europe.

Unlike the West, where a rising bourgeoisie took the lead, in Tsarist Russia it was the autocratic regime rather than the small and politically weak bourgeoisie that drove the modernization process forward. Intent on maintaining Russia’s archaic social and political order while simultaneously maintaining its great power status, the regime succeeded in speeding up industrialization, but was not prepared to deal effectively with the social and political contradictions that resulted from it.

For Le Blanc “the crisis of Russian capitalism . . . was also a crisis of the Tsarist order, which was multiplied and intensified by the overwhelming pressures of the First World War.” (51) He devotes considerable space to the evolution of the enormous and diverse Russian peasantry, which in 1914 constituted 85 percent of the population and was therefore of decisive importance to any political change that might occur.

He also closely examines the rise of the highly differentiated industrial working class, only a part of which was conscious of itself as a class with its own political interests. Although only a small minority before the war, it was a subset of this group that after 1905 gravitated into the orbit of Russian Social Democracy and would drive the revolution forward in 1917.

Le Blanc views the Bolshevik party as one of several “vanguard organizations” vying for influence in revolutionary Russia. Instead of focusing on traditional “Leninist” conceptions of the vanguard party stressed during the Cold War, he argues that the Bolsheviks were just one of the many groups striving to guide the sizable activist minority — the vanguard layer — that takes the lead in all revolutions.

Among the others were the bourgeois-liberal Constitutional Democrats or Kadet Party, the peasant oriented Socialist Revolutionary Party, and the Menshevik faction of the long-divided Russian Social Democratic Labor Party in which the Bolsheviks were the other main group.

Unlike virtually all other parties, which over the course of the summer of 1917 joined the Provisional Government and consequently came to share in its loss of legitimacy, the Bolsheviks — demanding the overthrow of the Provisional Government and its replacement by a soviet-based, socialist government that would end the war, improve food supplies, redistribute land to the peasants, introduce “workers’ control” of the factories and carry out elections to a Constituent Assembly — gradually gained the support of the majority of Russia’s increasingly radicalized urban working class.

In describing the revolutionary events, Le Blanc stresses the importance of the revolution from below in sweeping away the regime, but also balances this approach by emphasizing the centrality of leadership.

He notes Lenin’s decisive role in convincing his comrades that, rather than the consolidation of the new bourgeois republic, which virtually all Russian Marxists had believed necessary to create the social and economic basis for future socialist revolution, the party should use its new-found strength in the soviets to replace the Provisional Government with a socialist government based on an alliance of the urban working class and the peasantry.

Lenin was gambling that, in the context of the World War, this act would spark revolution across Europe. From a traditional Marxist point of view, without such an upheaval a “dictatorship of the proletariat” in isolated, underdeveloped, “peasant” Russia made little sense. And as Le Blanc points out, the ultimate failure of the revolution in the West did have devastating consequences for the development of the new regime.

Bolshevism in Flux

The author’s discussion of the events leading up to October would have been strengthened had he done more to outline the rich internal debates among the Bolsheviks after Lenin’s return to Russia in April.

This story would reveal how tenuous and malleable their politics were, for example, concerning the role of the soviets as catalysts of revolutionary transformation, their precipitation of the fiasco of the July Days and ensuing disarray in the face of repression when Lenin fled to Finland.

A closer analysis of these moments would reveal how the Bolsheviks’ ideas were constantly in flux and how debate and improvisation, down to the last moments before the seizure of power, characterized the party’s internal life and politics.

Since few socialists anywhere had actually thought much about the practical measures necessary to create socialism, improvisation also would be the order of the day in the Bolshevik government’s efforts to create the new order. Indeed, given the later metastasizing of the “proletarian” state, it is surprising that Le Blanc says virtually nothing about Lenin’s State and Revolution, written in August of 1917, where he outlines his vision of the post-revolutionary order in which the state would wither away as communism develops.

In the face of Russia’s grim realities, this misplaced optimism would soon give way to a much more hardheaded, and often brutal, Realpolitik.

Le Blanc shows how the new revolutionary government promoted workers’ power in the soviets and in the factories while at the same time suppressing its enemies. He stresses that initially the Bolsheviks were open to a socialist coalition government based on agreement with the platform recognized by the Bolshevik-dominated Second Congress of Soviets of Workers and Peasants’ Deputies, which had convened immediately after the seizure of power.

He also emphasizes that the Bolsheviks had no intention of establishing a “socialist” economy in underdeveloped Russia, opting for a “mixed economy” in which workers would have enhanced control over their workplaces.

The lion’s share of the book then examines how these intentions were undercut in the face of conflict with counterrevolutionary forces at home, with foreign invasion, and with international isolation. In order to survive, Le Blanc argues, the Bolsheviks took decisions that often contradicted the principles on which the revolution rested.

Once civil war erupted in the summer of 1918, all efforts focused on defeating the enemy militarily and politically. With the economy collapsing due to disruptions in the supply of raw materials along with widespread capitalist sabotage, the government undertook a series of improvised measures which, taken together, came to be known as “War Communism” because they effectively ended capitalism in Russia for a time.

These included rationing virtually all goods, centralizing economic power in the hands of the state, militarizing industry, and seizing grain from peasants who resisted handing over their crops for nothing in return.

Politically, it included gradually shutting down all opposition forces in the soviets, reintroducing censorship, resorting to murderous terror against all perceived opponents and sharply curtailing debate within the Party itself. Drawing on observers such as Victor Serge, who served the revolution loyally while also criticizing it, Le Blanc rightly points out that the implementation of “War Communism” required the massive expansion of the government apparatus.

The state bureaucracy quintupled in size from 1918-1919 from about 114,000 to 529,000, while party membership more than doubled, from 115,000 to 251,000. In the context of the civil war, the democratic promise of the revolution’s early days, and the hopes among some Bolsheviks for a rapid transition to communism, gave way, as Steven Cohen put it, to “a ruthless fanaticism, rigid authoritarianism, and pervasive ‘militarization’ of life on every level.” (159)

The power of the bureaucracy supplanted workers’ power in the increasingly moribund soviets.

By 1921, the Bolsheviks had defeated their domestic enemies but, with the revolution stalled in the West and the economy in ruins, the country could only be revived by reintroducing elements of capitalism in the countryside and relaxing government controls over small industry (the so-called New Economic Policy or NEP).

Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks maintained their political dictatorship while trying to promote renewed upsurge abroad through the Communist International. When that upsurge did not materialize, the question of the way forward become acute.

Under NEP the economy revived and the Soviet Republic consolidated itself. Workers gained some social benefits, peasants had de facto control over their farms, and cultural life within state-determined limits flourished, but the contradictions of capitalism also reemerged and it was unclear how they could be overcome.

The power to resolve that question, however, was not concentrated in the soviets, but rather in the ever-expanding state and party apparatus, in which a struggle for control was well underway by the time Lenin died in 1924.

Blind Spots and Contradictions

Le Blanc examines these complex issues from many angles, but his discussion of democracy and several “blind spots” in the Bolshevik approach are most important. The first involved “an insufficient theorization and comprehension of the dynamics and requirements of democracy,” the second their oversimplified understanding of the peasantry, and the third a “lack of awareness of the nature of bureaucracy.”

While these interrelated blind spots are all important to our understanding how the revolution slid toward authoritarianism, the most important, and most obvious contradiction in Bolshevik policy, was the effort to maintain a “proletarian dictatorship” in a largely peasant country where most peasants, while they did not want a return to the old order, also wanted little to do with the Bolshevik-controlled soviets.

In the short term, most Bolshevik leaders viewed the peasants as suppliers of food and recruits for the Red Army. Over the long term they believed the peasantry, as a group, had no future and treated them as second-class citizens. It was not surprising that, by the end of the twenties, the “worker-peasant alliance” was in tatters.

More broadly, however, I would also argue that the Bolshevik assertion that the soviet model that arose in Russia had to be applied everywhere else was equally flawed and, over the long run, ruinous.

Schooled for half a century on the centrality of parliamentary institutions for the achievement of socialism, when revolution swept much of Central Europe in 1918, many Western European socialists who had opposed the war and joined the revolution were also concerned that adopting a purely soviet based system — from which non-proletarian groups would be excluded — was a recipe for civil war, further destruction and a hindrance to building socialism.

Rejecting alternative models (parliamentary or otherwise) as counterrevolutionary, the Bolsheviks used the Communist International to split “reformists” from “revolutionaries” in the socialist ranks across the globe.

The result was to deepen the rift in the labor movement precipitated by the war and to consolidate what became warring social democratic and communist camps. The disasters that soon followed in Germany, Italy, and elsewhere are well known.

Le Blanc is careful to remind us that the “Communist tragedy” following the “Bolshevik triumph,” culminating in Stalinism, was not inevitable and should not lead one to abandon hope in the efficacy of revolution. While revolutions may fail, insurgencies have also brought about qualitative improvements — political, economic, social, and cultural — that cannot be denied.

Yet his study, rooted in an historical materialist approach, also reminds us of the decisive role of material factors or “historical realities” in shaping revolution.

In the Bolshevik case, Lenin and his comrades made an inspiring wager when they attempted to unleash an international socialist revolution by taking power in an undeveloped country. But the failure of the revolution to spread then left them to face powerful internal and external enemies in bloody struggles that undermined the revolution’s democratic promise and led to its tragic demise under Stalin.

November-December 2018, ATC 197