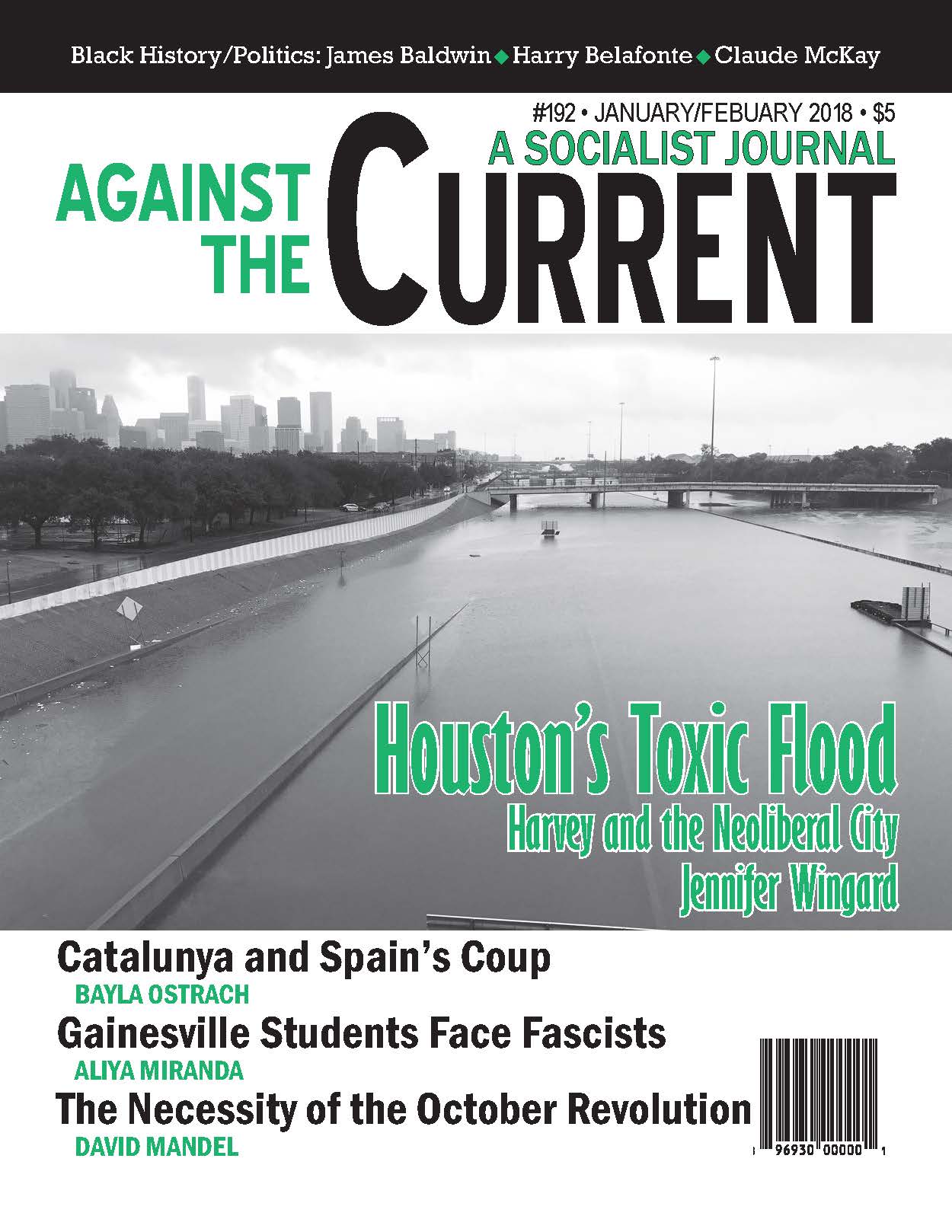

Against the Current, No. 192, January/February 2018

-

Open and Hidden Horrors

— The Editors -

The #MeToo Revolution

— The Editors -

Black Nationalism, Black Solidarity

— Malik Miah -

Harvey's Toxic Aftermath in Houston

— Jennifer Wingard -

Florida Students Confront Spencer

— Aliya Miranda -

How the UAW Can Make It Right

— Asar Amen-Ra -

The Kurdish Crisis in Iraq and Syria

— Joseph Daher -

Kurds at a Glance

— Joseph Daher -

Clarion Alley Confronts a Lack of Concern

— Dawn Starin -

Catalunya: "Only the People Save the People"

— Bayla Ostrach -

Catalunya: Organizations at a Glance

— Bayla Ostrach -

Catalunya: Abbreviated Timeline

— Bayla Ostrach - Egyptian Activists Jailed

- On the 100th Anniversary of the Russian Revolution

-

The October Revolution: Its Necessity & Meaning

— David Mandel -

Theorizing the Soviet Bureaucracy

— Kevin Murphy - Reviewing Black History & Politics

-

Race and the Logic of Capital

— Alan Wald - Black History and Today's Struggle

-

Racial Terror & Totalitarianism

— Mary Helen Washington -

Portrait of an Icon

— Brad Duncan -

Lessons from James Baldwin

— John Woodford -

New Orleans' History of Struggle

— Derrick Morrison -

Claude McKay's Lost Novel

— Ted McTaggart - Reviews

-

Language for Resisting Oppression

— Robert K. Beshara - In Memoriam

-

Estar Baur (1920-2017)

— Dianne Feeley -

William ("Bill") Pelz

— Patrick M. Quinn and Eric Schuster

Brad Duncan

Becoming Belafonte:

Black Artist, Public Radical

By Judith E. Smith

University of Texas Press, 2014, 352 pages, $24.95 paperback.

EVEN THOUGH HIS name is synonymous with standing up against injustice, the extent to which Harry Belafonte’s political commitments have their roots in the radical left of the 1940s and 1950s has been largely obscured.

The story of how a young man born in Harlem to a Jamaican mother came to be involved with Black leftists, the most radical labor unions, militant antifascists, anti-colonial activists and Communist folksingers has never fully been told. Nor has Belafonte’s meteoric rise to pop stardom in the mid-1950s or his years making Hollywood films been subject to the kind of critical examination that Judith E. Smith gives us with Becoming Belafonte: Black Artist, Public Radical.

Born in Harlem in 1927 to working-class parents from Jamaica and Martinique, Belafonte’s childhood was divided between Harlem and Jamaica. Harlem’s streets exposed Belafonte to a rich tradition of militant activism, from Black nationalist street orators to neighborhood battles against police brutality.

When he moved with his mother to Jamaica to find work at the height of the Depression he was exposed to the brutality of British colonialism, but also saw workers on strike. Even joining the Navy was no escape; even donated blood was segregated in the military.

Racism and extreme exploitation on the streets of the United States and Jamaica were seared into Belafonte’s young mind. From his teen years onward, Belafonte was animated by a burning desire to topple these interconnected power structures, from colonialism to Jim Crow.

The first half of Becoming Belafonte takes a look at Belafonte’s early years of political and artistic development in New York City in the 1930s and 1940s. Smith tells the story of Belafonte’s political awakening against the backdrop of police brutality in his Harlem neighborhood, segregation in the military, and labor battles.

When a young, politicized Belafonte discovers a hidden world of like-minded Black and white artists who are committed to using music and theater to combat racism and exploitation, his course is set. This constellation of activist-artists, many shaped by the Communist Party’s cultural activism during the Popular Front period of the 1930s, provides a homebase and a context for Belafonte’s trajectory as an artist.

The second half of the book is an analysis of Belafonte’s work during his years as a leading star in pop music and Hollywood. Belafonte thought strategically about how to use music, theater, and film to dismantle not just Jim Crow segregation, but white supremacy itself.

Smith uses that understanding to examine the intentions, politics, and impact of nearly every film and television performance from the mid-1950s through the mid-’60s.

Radical Cultural Milieu

The radical cultural activism of the Popular Front era has been widely studied, and with good reason. But Becoming Belafonte examines the activities of leftist performing artists in the years that followed that zenith, when the seeds planted in the 1930s continued to find ways of growing up through the concrete.

Even as anticommunism intensified in the late 1940s, there remained in New York City a whole world of pro-labor, anti-racist, and socialist artists writing plays, staging musical cabarets, and writing political literature.

Belafonte discovered this world by accident. An older woman for whom he was doing odd jobs gave him a ticket to see a production of Home is the Hunter put on by the American Negro Theater (from 1940-49, a community theater project growing out of the “Negro Unit” of the Federal Theatre Project in Harlem — ed.).

The play explores the conflict between a returning vet who sympathizes with fascism and his pro-labor wife. Belafonte was absolutely mesmerized, both by the Black actors playing realistic Black characters and by the play’s willingness to look at political issues such as racism, labor unions, and fascism.

Soon he’s not just attending theater but acting as well, swimming in a whole milieu of young political theater people, including his new friend Sidney Poitier. He performs in a play by the Irish playwright Sean O’Casey (1880-1964, a non-party communist) in which the Irish characters are played by Black actors with Caribbean accents, providing a fresh context for the play’s critique of imperialism.

Paul Robeson, who perhaps personified Belafonte’s growing interest in merging theater, music, Black culture and left politics, approached him after a performance to say he would soon be visiting O’Casey in London and was eager to tell him about the brilliant re-contextualization of his play. Belafonte had found a home, a mentor, and a calling.

At age 19, Belafonte was fresh out of the Navy and spending most of his time around New York’s radical theater scene. He enrolled at the Dramatic Workshop at the New School in Greenwich Village; a more ideal setting for a teenager interested in the political potential of theater would be hard to imagine.

The young actors that Belafonte met downtown included Bea Arthur, Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis and Walter Matthau. Mixing genres and performance disciplines was a part of the cultural left’s aesthetic at the time.

A suave, polished blues singer like Josh White shared the stage with a folksinger performing work songs; modern dancers shared the stage with humorous skits about workers on strike. The respective sounds of Woody Guthrie and Duke Ellington co-existed quite happily in the world of the 1940s New York Left.

Belafonte was attracted to the idea that performing folk songs from around the world was an act of proletarian internationalism, a musical illustration of the fact that workers of all lands shared common burdens and had a common future. He also became firmly convinced that he could use the music of the African diaspora — from calypso to jazz to African pop — to challenge racist assumptions about Black people and Black culture.

Belafonte was constantly networking and connecting with artists and performers who shared his vision, working as an actor and as a singer. One night he’s performing with Pete Seeger and the left labor troubadours around People’s Songs; the next night he’s digging bebop at the Royal Roost where drummer Max Roach asks him to sing; the night after that he’s deep in conversation with James Baldwin about how to build a national movement against Jim Crow.

He’s not making much money as an actor who moonlights as a nightclub singer, but his popularity is growing with every performance.

Facing Repression

Smith’s wonderfully researched examination of Belafonte’s evolving relationship to this world of postwar radicalism and pre-Civil Rights Movement Black cultural activism is by far one of the most engrossing and rewarding aspects of Becoming Belafonte.

But the growing Red Scare threatened to destroy much of the cultural world where Belafonte the actor and singer was growing and thriving. In a foreboding sign of things to come, a 1949 concert by Paul Robeson in Peekskill, New York was halted when an anticommunist mob chanting racist and antisemitic slogans rioted and attacked the stage.

Founded in 1947 with the aim to “expose racial discrimination in the radio and television fields,” the Committee for the Negro in the Arts (CNA) was an organization that Belafonte was eager to work with. He signed on to their call for a conference “On Radio, Television, and the Negro People” in 1949, a time when television was just beginning and it was not yet clear if the medium would be as openly racist as radio always had been.

The stereotypes pushed by popular radio shows, and the lack of hiring of Blacks for production and performance work, were at the top of CNA’s agenda, which reflects the conversations that Belafonte and other young Black actors and artists had been having for years. Initiated by members of the National Negro Congress (which had been organized in 1936 during the Communist Party’s Popular Front period), CNA was in the cross hairs of the House of Un-American Activities Committee.

Belafonte was undeterred by this increasingly hostile political climate; in 1952 he moved to Hollywood to try to break into films while still developing his musical act. Although his charisma, artistry and good looks were continuing to win him critical praise and new fans, racial segregation and growing anticommunism put hurdles in his path at every turn.

Every time Belafonte inched closer to stardom, the Red Scare threatened to snatch it all away. When his name was listed in Counterattack, the corporate-funded periodical aimed at exposing Communist influence in U.S. society, it looked like it could be all over.

Miraculously Ed Sullivan, himself a dedicated anticommunist, nonetheless asked Belafonte to sing on his taste-making “Toast of the Town” show. But even as Belafonte was in Hollywood working for his big break, HUAC was questioning his ex-wife about his connections to the left and his relationship with W.E.B. DuBois and Robeson.

Finally in 1956 it all came together; his film Carmen Jones was incredibly successful critically and commercially. It was in Belafonte’s words, “the first Black film” and not merely a film with some Black characters.

That same year he released the album Belafonte, which brought the Jamaican music of calypso to a mass pop audience. “Day-O,” a labor song of Jamaican banana workers, exposed a pop audience to a dimension of diasporic culture they were unfamiliar with — hence broadening their conception of Black culture — and did so using a song about working-class life.

While the rock and roll craze was aimed solely at teenagers, Belafonte’s calypso folk-pop reached many demographics. He was the first Black heartthrob, on televisions and movie screens across the country, and his records sales were literally setting records. And all of this was happening just as Brown v. Board of Education and the Montgomery Bus Boycott were challenging U.S. racial politics in unprecedented ways.

Creative and Movement Commitments

Offers for Belafonte to appear on television flooded in, but Belafonte boldly used his new star leverage to insist that he have more creative control over his appearances. While television producers insisted that “the Southern market” would never go for a performer like Belafonte, he was simply selling too many records and movie tickets to ignore.

The emerging Civil Rights Movement couldn’t ignore him either. Not long after the bus boycott started, Dr. Martin Luther King asked to speak with Belafonte. Belafonte was very skeptical of mainstream Civil Rights groups and leaders, as he felt many of them had abandoned DuBois and Robeson when they were being redbaited.

Belafonte and King immediately clicked, however, and Belafonte became increasingly involved with the movement in the South. This was a period when Nat King Cole was attacked by a white supremacist while on stage and when redbaiting could take Belafonte‘s career away at any time, yet Belafonte eagerly deepened his connections to the movement against segregation.

In 1959, after considerable struggle, Belafonte was able to produce a hugely successful television special called Tonight with Belafonte, a “portrait of Negro life in America, told through song.”

The special showcased Black artists from folksinger Odetta to modern dancer Arthur Mittchell, from blues artists Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee to ballet dancer Mary Hinkson. Producers and advertisers said it would never work, but it was a smash and won an Emmy.

Portrayals of Blacks in mass media were starting to change, and Belafonte was making sure of it. He also became increasingly interested in the anti-colonial movements in Africa, clearly seeing the struggle against colonialism and white minority rule and U.S. segregation as deeply connected.

After hearing Oliver Tambo of the African National Congress speak in 1960, he connected with the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. Belafonte took a particular interest in helping the career of the South African singer Miriam Makeba, whose music was bringing African music and an explicit anti-apartheid message to a new audience.

The Red Scare made expressions of solidarity with anti-colonial struggles highly risky, especially from Black activists looking to link movements in Africa with the struggle against racism in the United States. But Belafonte was animated by the same internationalism that guided his mentor Paul Robeson.

Belafonte was also collaborating with young activists in the Civil Rights Movement who were using music, such as the SNCC Freedom Singers, helping them tour and record. He was harnessing his enormous star power to aid movements against white supremacy.

Activist Debates

One of the richest aspects of Becoming Belafonte is its treatment of the debates around the goals of Black activists in the performing arts.

What kinds of roles should be written for Black actors? What roles should Black actors refuse to take? Should they emphasize the uniqueness of Black culture, or instead show the universality of Black experiences? How should film balance a political message with multi-dimensional characters?

Smith looks at how white film critics wrote about Belafonte’s work as well as how the Black press covered him. Smith examines which films accomplished their goals and which were seen by Belafonte (or critics) as stilted or clumsy.

These are the central questions that Belafonte and his peers were grappling with in the 1950s into the early 1960s. They are related to questions Belafonte encountered in the 1940s cultural left about representation, authenticity, and how to communicate a political message through the performing arts to a truly mass audience.

In addition to these vital debates about art and activism, Smith examines how Belafonte delicately managed to navigate the Hollywood star machine while utilizing fame to directly aid mass movements. Becoming Belafonte is also enormously useful as a history of the Black cultural left in the decade between the end of World War II and the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Even readers who already think of Belafonte as unflappable will be amazed by his audacity and determination, from starting a Black-owned film studio in the middle 1950s to routinely turning down high profile gigs when his political vision would be compromised.

Readers will have their eyes opened to the intimate connections between the politics of the 1940s radical left and the hit songs and films of Harry Belafonte, connections that previous treatments have not explored in such depth.

Becoming Belafonte is an engrossing and expertly researched book that should be read by scholars of 20th century Black internationalism and the cultural left in the decade after World War II, by those interested in how the early Civil Rights Movement impacted television and film, and by activists searching for ways to use music and film to build movements against white supremacy and capitalism today.

January-February 2018, ATC 192