Against the Current, No. 190, September/October 2017

-

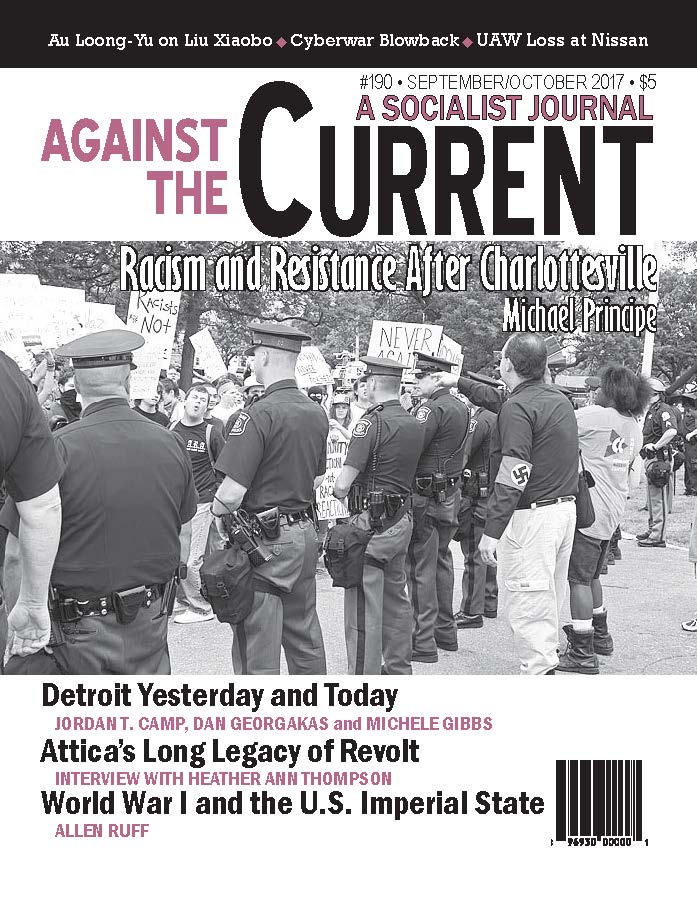

The War Is At Home

— The Editors -

When White Supremacists March

— Michael Principe -

Choices Facing African Americans

— Malik Miah -

How the UAW Lost at Nissan

— Dianne Feeley -

Did Scandal Tip the Balance?

— Dianne Feeley -

NSA's Cyberwarfare Blowback

— Peter Solenberger -

The Murder of Kevin Cooper

— Kevin Cooper -

Attica from 1971 to Today

— interview with Heather Ann Thompson -

The Trial of Sacco and Vanzetti

— Marty Oppenheimer -

Mourn Liu Xiaobo, Free Liu Xia

— Au Loong-Yu -

Under Attack at San Francisco State University

— Saliem Shehadeh -

Dawn of "Total War" and the Surveillance State

— Allen Ruff -

Solidarity Message to Egyptian Website

— The Editors - Fifty Years Ago

-

Detroit's Rebellion & Rise of the Neoliberal State

— Jordan T. Camp -

Chronicle of Black Detroit

— Dan Georgakas -

For Mike Hamlin

— Michele Gibbs -

Mike Hamlin (1935-2017)

— Dianne Feeley - Suggested Readings on/about Detroit's 1967 Rebellion

- Reviews

-

BLM: Challenges and Possibilities

— Paul Prescod -

The People vs. Big Oil

— Dianne Feeley -

Immigration's Troubled History

— Emily Pope-Obeda -

Paradoxes of Infinity

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

Mourn, Then Organize Again

— Michael Löwy -

Making Their Own History

— Ingo Schmidt -

The Wheel Has Come Full Circle

— Mike Gonzalez

Dianne Feeley

Refinery Town

Big Oil, Big Money, and the Remaking of an American City

By Steve Early

Foreword by Bernie Sanders

Boston: Beacon Press, 2017, 222 pages, $27.95 hardback.

REFINERY TOWN TELLS the story of how a small, formerly industrial city — with a population just over 100,000 — attempts to fight its way out of the hell that segregation, joblessness, pollution and violence have imposed.

Richmond, California’s one remaining major industry, Chevron’s sprawling refinery, can produce 240,000 barrels of crude daily. Six-hundred-ton oil tankers unload at its dock. In 2013 alone the plant generated $20 billion in annual revenue and about two billion in profit. Its impact on the local community has been as large as the profits it takes. Safety has long been an issue for both the unionized work force and city residents; Chevron has had an outsized influence on local politics as well.

Steve Early, author of three previous books including Save Our Unions: Dispatches from a Movement in Distress, moved to Richmond in 2011. He writes about his new home from the viewpoint of an experienced journalist and labor organizer. He reads books and reports, talks to workers, residents, experts and officials.

Early outlines the city’s industrial history. The refinery, which began as a Standard Oil refinery in 1905, staved off unionization until after World War II. Producing fully 10% of Chevron’s profits, the facility outlasted the enormous Kaiser shipyards and nearly five dozen defense-related industries that turned Richmond into a boomtown during that war.

Refinery Town is a hopeful book, as it details how a coalition built itself into what became Richmond Progressive Alliance (RPA) and took on the corporation in David-and-Goliath battles. With its stance of rejecting corporate contributions, RPA has managed to combine grassroots and electoral activism, and developed alternatives to austerity, corruption and deindustrialization.

Refiney Town’s first chapter begins with Chevron’s August 2012 fire, after which an estimated 12-15,000 people sought medical care. On the disaster’s first anniversary, Mayor Gayle McLaughlin and Bill McKibben, founder of 350.org, addressed a crowd of 2,500. The next day the city filled a suit against the corporation, accusing it of “years of neglect, lax oversight, and corporate indifferent to necessary safety inspection and repairs.”

The ongoing demand to force Chevron to implement and continually upgrade safety procedures as well as pay its fair share of taxes is a thread running throughout Early’s account. Accustomed to throwing its money around to get what it wants, the corporation shelled out millions to defeat RPA candidates and the initiatives they supported.

Whether initiating campaigns or partnering with others, RPA attempts to broaden its outreach through meetings, election campaigns, petitions, demonstrations, even direct action at Chevron’s plant gates. Interestingly, Early recounts the solidarity bond that developed between Richmond and Ecuador over Chevron’s pollution.

Ecuador maintains that toxic waste in the Lago Agrio rain forest, where Texaco (now Chevron) had its site, is causing skin infections, rare cancers, miscarriages and birth defects. A delegation from Richmond visited Lago Agrio; McLaughlin then arranged a public screening of Crude: The Real Price of Oil, a documentary about the Ecuadoran lawsuit. When Chevron issued a statement saying that the Mayor should mind her own business, McLaughlin responded:

“Chevron is not only polluting our air and water….They’re polluting our politics and legal system. So we’re building an international ’union of affected people’ that can turn our shared pain and suffering into the power to change things.” (69)

It’s important to note that the campaigns RPA championed have not always won, and even those that have are not complete triumphs. For example, Chevron’s settlement two years after the 2012 fire included $90 million earmarked for environmental and community programs. But left aside was the demand RPA and other organizations raised that Chevron bail out the nearby public hospital, which served 250,000 area residents and treated many who sought treatment after the fire.

Intimidated by high-ranking Democratic Party officials and Chevron’s threat to sue the City Council for “overreaching” in its demands, the majority on the City Council decided not to fight for the hospital and the jobs and services it provided. Within six months it was forced to close. (128-130)

How RPA Came Together

During Ralph Nader’s presidential campaign in 2000, a Richmond group cohered around opposition to the construction of a municipal power plant right next to the oil refinery. After mobilizing the community to speak at public meetings, and calling instead for exploring alternative energy sources, the Richmond Alliance for Green Public Power and Environmental Justice were successful in getting the project scrapped.

They went on to force the City Council to adopt a stronger industrial ordinance to reduce the risk of refinery fires, explosions and chemical spills. (44)

Following the City Council’s ban on sleeping in public places, the Alliance organized against police harassment of the homeless. With the growth of the city’s Latino population, police had been targeting as “vagrants” day laborers looking for work in front of Home Depot. Spearheaded by Juan Reardon, the group encouraged the workers to develop the Richmond-El Cerrito Day Laborers Association, which was eventually able to work out a 10-point agreement with the police department.

As a result of these successful campaigns, the organization broadened itself, becoming the Richmond Progressive Alliance. It decided to field candidates for City Council in November 2004. The plan was to run candidates who would reflect the city’s racial and ethnic diversity. This proved to be a complicated task given the cozy relationship Chevron maintained with some of the Black community organizations, churches and longtime politicians.

Since candidates were running for non-partisan offices, the RPA was able to run people from different political perspectives (Greens, Democrats, socialists, non-affiliated). What bound the candidates together were the RPA principles of combining grassroots activism with an electoral campaign and what became its trademark rejection of corporate donations.

The RPA candidates kicked off their campaign with a public forum featuring out-of-town stars — Matt Gonzalez, Green Party member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, Dennis Kucinich, campaigning for the Democratic Party nomination for president, and environmental justice activist Van Jones. They drew a crowd of 600 and then went on to convene a People’s Convention that set the policy goals for their campaign that “another Richmond is possible.” (47)

Of the two RPA candidates, Andrés Soto was a leader within the Latino community and had been a victim of police brutality. Through mobilizing the Latino community, he won a $175,000 settlement and a recommendation from the police commission that one officer be fired. This made Soto the target of both the Richmond Police Officers Association and the firefighters local. The other RPA candidate, Gayle McLaughlin, who wasn’t taken seriously by the powers that be, actually won office.

As the one RPA activist on the City Council, McLaughlin championed safe and quick cleanup of the city’s toxic sites and established its regulatory oversight. This also curbed the corporation’s use of non-union contractors. She backed a successful campaign to get the Bay Area Air Quality Management District to adopt first-in-the-nation flare control legislation and joined with City Councilor Tom Butt to oppose Chevron’s privileged rate as a utility user.

McLaughlin was only able to accomplish this through working in a coalitional tent that RPA helped to build. Two years later McLaughlin narrowly won the mayor’s office in a three-way race and served two terms. She has been joined on the council over the years by other RPAers.

With the 2016 elections five of the seven city councilors are now RPA members: McLaughlin, Jovanka Beckles (an Afro-Panamanian first elected in 2010), Eduardo Martinez (a retired teacher, and Latino first elected in 2014), and two recently elected: Ben Choi (an Asian American who works for Marin Clean Energy) and Melvin Willis (an African-American organizer for the Association of Californians for Community Development — ACCE).

They ran as a “Team Richmond” slate. These days the current mayor, Tom Butt, is an RPA critic, particularly because in 2016 RPA successfully campaigned for a rent control measure which Butt, as a landlord, strongly opposed.

What RPA Fights For

RPA defines itself rather narrowly in order to be a broad organization. For example, it does not call itself anti-capitalist although its hallmark is opposing corporate influence in politics. Its 2014 slate for city council included two persons registered Green and two registered as Democrats. That year, before Bernie Sanders made the term “democratic socialist” respectable nationally, the RPA candidate for mayor, Mike Parker, was an open socialist. (The story of Butt’s entry into the race and Parker’s withdrawal is described in Early’s book.)

By the end of Refinery Town, RPA is attempting to transform itself into a membership organization that reflects the ethnic diversity of the city. In the process RPA has worked with environmental organizations and unions to develop innovative proposals to deal with the problems Richmond faces.

Over the course of its existence, RPA city councilors in coordination with its membership and coalition partners have been able to win some important reforms but even when they came up short, they carried out educational work to lay the groundwork for the future.

Some gains have been small, but important, such as creating city identification cards or “banning the box,” i.e. outlawing the practice of having prospective employees reveal if they’ve ever been arrested.

Early devotes a chapter to Richmond’s struggle to turn around the notoriously buddy-buddy, corrupt and viciously violent police department. Since hiring an outsider, Chris Magnus, to be the police chief in 2005, violent crime was reduced by 23% and property crime by 40%. In a city with 20% poverty, the City Council opened up parks and recreation centers and has developed and funded a program that hired six fulltime youth mentors with past prison or gang experiences to work with at-risk youth.

Between 2008 and 2014 there were no fatal shootings of a Richmond resident by the police. Early attributes the success of the community-policing model over one decade to replacing all but 12 officers on the force and instituting de-escalation training. He quotes Magnus as remarking, “It’s easier to get new people in a department than it is to get a new culture in a department.” (80)

But a police shooting in the summer of 2014 resulted in the death of 24-year-old Richard Petro Perez III. The county district attorney ruled the officer had acted in self-defense and he was returned to duty — even before the Richmond Police Department completed its investigation. This confirmed for Perez’s family that police are not held accountable for their actions, and in fact are protected.

Since that murder, every fatality or serious injury in which a police officer is involved must be investigated, and civilian oversight has been beefed up. The renamed Citizens’ Police Review Commission, however, is still forced to operate within the constraints of California’s “bill of rights” for police, which prevents the examination of personnel files for charges of misconduct.

Constraints on Reform

The reality is that the RPA’s campaigns come up against state or federal laws, or are faced with the constraints of inadequate government funding at the county, state and federal level. For example, when the City Council passed a motion in 2013 to use eminent domain in order to stop the mortgage foreclosure crisis and resulting blight, it came under intense pressure from the real estate and banking industries.

Although RPA and its ally ACCE went door to door to counter the propaganda the industries unleashed, the reality was that without allies in neighboring cities willing to pass similar motions, the idea was dead in the water. The following year Congress passed, and President Obama signed, a law forbidding the use of any federal role in mortgage financing of homes taken through eminent domain. That blocked the trail RPA had attempted to blaze. (63-67)

RPA suffered a more spectacular defeat in 2012 when it went up against Big Soda. At the urging of Dr. Jeff Ritterman, an RPA member serving on the City Council, RPA campaigned for Measure N, which would levy a one-penny-per-ounce tax on sugary drinks. The money would be used to fund youth programs including sports teams, school gardens and cooking classes, helping to prevent childhood obesity.

Launching an educational campaign about the health benefits, RPA was overwhelmed by Big Soda, which contributed $2.5 million to defeat the measure, and did so by a 2-1 margin. Chevron’s political action committee, Moving Forward, spent another $1.2 million on the 2012 election; neither of the two RPA candidates for city council won. (Dr. Ritterman later spearheaded similar and successful tax proposals in Mexico, San Francisco and Berkeley.)

Early candidly examines the issues RPA has faced, which makes his account compelling, particularly for activists. He presents the problems an underfunded city government faces even with a serious team of city councilors. Thanks to the tax ceiling in the 1980s-era Proposition 13, Early points out that Chevron saves $225 million statewide in taxes and $30 million locally.

Above all else RPA takes up the issues of inequality as they manifest themselves on residents. The city of Richmond can only do so much, and it seems RPA understands its limits, always pushing them, working to mobilize the community and asserting the right to an alternative.

Since the book was published, Gayle McLaughlin has announced her candidacy for lieutenant governor of California and Jovanka Beckles is running for state assemblyperson in 2018. Both are running as “corporate-free” candidates in the state’s “open primary.” (There are no party primaries; everybody runs on the same ballot and the top two go to the general election. This system has been used in California since 2012.)

These two candidates have pledged to accept no corporate money. McLaughlin is registered “no party preference” while Beckles is a registered Democrat.

RPA members are using these campaigns to spread the RPA model in California and to draw people energized by the Bernie Sanders campaign into ongoing organizations.

I was disappointed that there was no index to enable me to better follow the various issues over time, nor maps that might have given the reader a better sense of Richmond. Maybe that’s an idea for the paperback edition?

September-October 2017, ATC 190