Against the Current, No. 189, July/August 2017

-

The Longest Occupation

— The Editors -

One-Half Cheer for Trump?

— The Editors -

Marching for Science and Humanity

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

California Science Marches

— Claudette Begin -

Confederate Monuments Down

— Derrick Morrison -

Theresa May's Katrina

— Sheila Cohen and Kim Moody -

USAID in El Salvador: The Politics of Prevention

— Hilary Goodfriend -

China's Ancient Labor Party

— Au Loong-yu - Sweatshop Shoes for Ivanka

- Fifty Years Ago

-

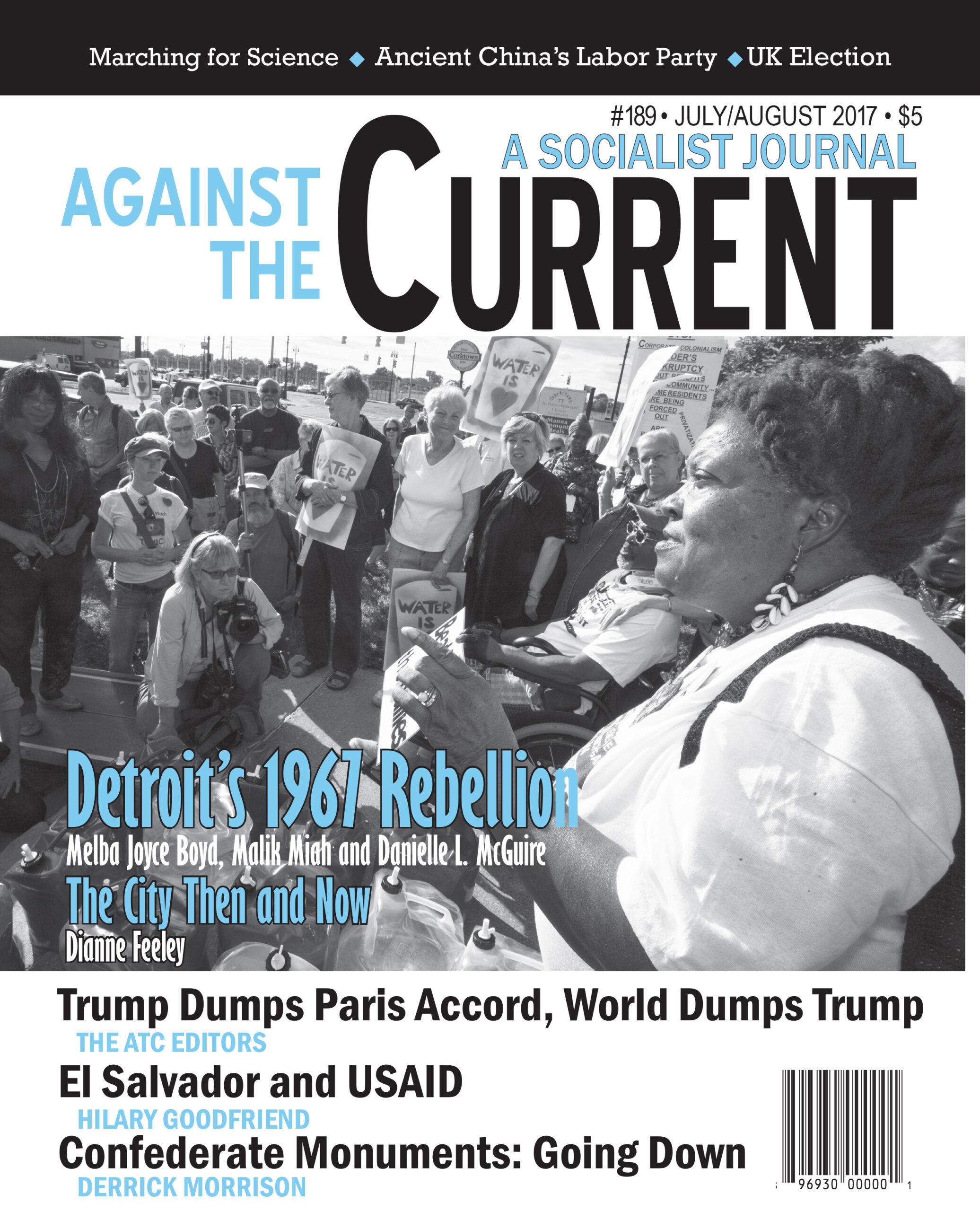

Detroit's Rebellion at Fifty

— Malik Miah -

Roots of the Rebellion

— Kim D. Hunter interviews Melba Joyce Boyd -

Murder at the Algiers Motel

— Danielle L. McGuire -

A Tale of Two Detroits

— Dianne Feeley - Reviews

-

Birth of the "Open Shop"

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Teachers as Change Agents

— Marian Swerdlow -

The World and Its Particulars

— Luke Pretz -

The Unraveling Middle East

— Kit Adam Wainer -

The World Through African Eyes

— Anne Namatsi Lutomia -

Poland's Solidarity and Its Fate

— Tom Junes -

The Russian Revolution: Workers in Power

— Peter Solenberger

Malik Miah

DETROIT FOR MUCH of the 20th century was a center of Black intellectual radicalism and militant agitation against white racism. From the days of the Marcus Garvey nationalist movement in the early decades of the century, to Malcolm X, revolutionary autoworkers and the Black Power movement in the 1960s, Detroit was front and center in debates on strategy and tactics to win Black freedom.

African Americans did not practice quiet acceptance of the status quo. Many even turned to socialist ideas.

For five days in July 1967, a spark lit the fuel of deep anger that shook the city, state and country. Some 43 people, a majority Black (33), were killed as the city cops, state National Guard and Federal troops used tanks and war weaponry to suppress the community.

The resulting debates about what these events meant and what to do next moved quickly from reforms by the government to a need for more radical change.

White domination is rooted in racial oppression that had kept Blacks in their place since the Great Migration from the South. The white rulers did not expect any fundamental change after the brutal putdown of the 1967 rebellion.

Rebellion, not Riots

The 1967 rebellion reflected deeper political and economic problem that African Americans suffered then (and continues today). The class division that always existed within a segregated Black population became more pronounced with the rise of a new Black political and economic middle class.

The 1967 rebellion showed the depth of the crisis of the United States: “two nations, one black and one white, separate and unequal” in the language of the 1968 Kerner Commission. The civil rights revolution did end formal de jure housing segregation and discrimination, but not the de facto realities.

The Republican Governor George Romney sent in the National Guard; the Democratic President Lyndon Johnson sent in the Army, while Democratic liberal Detroit Mayor Jerome Cavanaugh let loose the cops targeting “looters and rioters,” especially in the near west side and east side of the city where most African Americans lived.

After the five days of the “12th Street rebellion,” Johnson set up the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (the Kerner Commission) to look at the fact that Blacks were angry and demanded fundamental change especially since the laws did not bring real equality.

The rise of the left wing of the civil rights movement, which began in the early 1960s, took off after the uprisings. H. Rap Brown, recently elected fifth chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), warned that if the city did not fix racial oppression the city would be burned down.

The Black Power Movement, to the left of the traditional civil rights groups, included revolutionary nationalist organizations such as the Black Panther Party and local formations. In Detroit, many militant Black workers in the auto plants leaned toward socialist ideas and created the League of Revolutionary Black Workers.

The 1967 rebellion was an important reflection of the deep anger. Unfortunately, liberal Black leaders, including some from the left, took advantage of the fleeing of the white elite and many working-class whites to the suburbs to take over political control of the city by the mid-1970s.

The Democratic Party became entrenched with Black faces. The problem was also seen in other cities where BEOs (Black Elected Officials) multiplied by the hundreds overnight, seeing it as their time to feed off the super-corruption of the ruling class.

What followed was the failure of Back liberalism in elected office. Some would argue this was inevitable because of white supremacy. The decline of manufacturing and the auto industry gave these BEOs an excuse.

Looking Back: The 1943 White Riot

To understand that Detroit’s post-’67 demise was not inevitable, look back at the “riot” 24 years earlier. In 1943, during World War II, the U.S. military was still segregated and Blacks faced limited job opportunities in the war industries.

The Great Migration of Blacks from the South (along with Eastern European immigrants) to the city led to its transformation. Detroit became one of the largest cities in the country by the 1950s (with a population that would peak at close to two million). However, whites did not see Blacks as fellow workers or equal Americans.

Instead, the racist ideology that portrayed African Americans as an economic and social threat to their way of life was pushed by the propaganda pundits of the time. When Blacks came to Detroit to work, they faced widespread discrimination in housing and employment.

How the city’s ruling elite responded was to separate the white immigrants from Black residents, who were pushed into what was known as “Black Bottom.” Black Detroiters understood that most sections of the city and near suburbs were off limits to them. (On Detroit’s interwar “racial liberalism” and its failures see Karen R. Miller’s essay in ATC 180, https://www.solidarity-us.org/node/4550.)

In the 1943 race riot whites, who were a clear majority of the population. also organized vigilante gangs and drove into Black areas and attacked the community as the cops did nothing. There were instances of Black self-defense in response to the racist assault.

Destruction of Historic Black Bottom

The 1943 anti-Black race riot did not lead to “white flight” as occurred after 1967. Whites knew they were securely dominant. As would be the case in 1967, the president was a Democrat (Franklin Roosevelt) and the Governor was a Republican. Both were white.

After World War II, Blacks faced more racism and subjugation across America. In the 1950s, Detroit’s ruling powers launched a campaign to demolish the near east side Black “ghetto” known as Black Bottom to make way for a new interstate highway. The entire area was bulldozed.

Black Bottom “was once the center of African-American life in Detroit, then It was razed in the name of urban renewal,” journalist Bill McGraw explains in his very insightful article, “Bringing Detroit’s Black Bottom back to (virtual) life.” (Detroit Free Press, February 27, 2017)

Then, in the early 1950s, in one of the most controversial episodes of mass gentrification in Detroit history, the virtually all-white city government bulldozed Black Bottom in the name of “slum clearance,” eventually to replace it with the Chrysler Freeway and Lafayette Park, an upscale residential community that initially was occupied by mostly white residents.

Black Bottom is so long gone that you have to be at least Social Security age to have walked its streets, and its memory fades a little each day.

The Ruling-Class Reaction

Detroit’s traditional white ruling class never planned to leave the city. Auto executives and others had built fancy homes in the city. The historic Indian Village, on the east side near the Detroit River and across from Windsor, Canada, was built for that reason. The homes are now labeled historic sites.

Yet as auto plants closed in the city and new ones opened in the mainly white suburbs, these executives moved out to Bloomfield Hills, Grosse Pointe and other wealthy areas. The future was not rebuilding a mostly Black city.

The Black political leaders had no serious plan to overhaul the city and educate the Black working class to the new industries. They mainly looked out for themselves. It is easy to blame racism and the white power structure. But there’s a lot of fault with the Black-led Democratic Party structures.

The Democratic Party until the late 1960s was a racist alliance of southern Dixiecrats (de facto Confederate sympathizers) and liberal Democrats in the North. The Black leaderships were divided. While northern Black Democrats supported integrating into the party as a way to make progress, southern Blacks did not see the Democratic Party as their party.

One wing of the rising Black movement favored creating an independent Black party. In Michigan, the Freedom Now Party was formed in 1964.

Since the 1970s, however, the power center of the Black establishment shifted from civil rights leaders to Black Elected Officials who support the system. It’s one reason why today’s new mass movements have taken so long to create.

It took some three decades of failures as seen in Detroit for a new generation to emerge. The Black Lives Matter Movement formed in 2012 after the murder of Trayvon Martin in Florida. The BLM relies on mass action and education, not elected officials to spearhead the fight for change.

Key Lesson of Rebellions

The 1967 rebellion is significant because it represented a high point of Black anger and laid the basis later militancy. Black labor militants and intellectuals moved toward socialism and revolutionary Black Nationalism and Pan Africanism.

This change clarified the race and class issues within the community. The solutions to structural racism are not working within the system. It didn’t work in cities like Detroit.

New organizations and perspectives that are openly anti-capitalist and against the big business system are tied to building a mass movement and a new leadership. If the new leaders follow the path of those who became absorbed by the two-party system, Blacks will continue to suffer great inequality and fewer economic advances.

The rise of the Black middle-class and professional layers who can escape poor communities will eventually suffer blowback from racists in power. The Trump presidency and far-right control of so many state legislatures show far voter suppression has gone.

The hope for the future is that a broad multi-ethnic working-class unity, based on anti-capitalism and anti-racism, can create a new mass movement. The unity of various formations including Black organizations fighting racism will be key to build a new leadership.

It will include young women and men from grassroots groups like Black Lives Matter and those who created the Occupy Wall Street anti-big bank movement.

The key lesson of 1967 (and 1943) is that so long as racial inequality is not rooted out and laws against racist practices forcefully implemented, counterrevolutionary movements against Blacks will arise and new explosions will occur.

The positive take is that new leaders and movement are coming forward (as in North Carolina) and mass protests are targeting Trump and the right wing almost daily.

July-August 2017, ATC 189